Abstract

Previous studies have examined the impact of the relationship between international nongovernmental organisations and the military on peacekeeping operations and humanitarian programming. However, how relations between international nongovernmental organisations and military actors affect preventing/countering of violent extremism has not been central to existing debates. By using the qualitative-dominant mixed methods approach, this paper investigates relations between these actors in Northeast Nigeria and argues that the dynamic interactions between international nongovernmental organisations and the military largely breed mistrust and conflict between them. This undermines the capacity of international nongovernmental organisations to prevent/counter violent extremism. The paper concludes that mutual respect for the operational procedures of the military and international nongovernmental organisations in the Northeast is relevant for an enhanced relationship between them and sustainable preventing/countering violent extremism programming in Nigeria and beyond.

Keywords

Introduction

Globally, counterterrorism (CT) emphasises hard power as the primary response of the military to terrorism. It is commonly used to restore law and order as well as preempt and retaliate terrorist attacks (Duyvesteyn 2008). Whereas this strategy is effective in dislodging terrorists (Clubb & Tapley 2018), it is largely repressive, non-viable and unsustainable (Nwangwu & Ezeibe 2019). It has also been criticised for a high level of human rights violations and generating tension between stakeholders in CT (Sampson 2016). This led to the evolution of an alternative strategy known as preventing/countering violent extremism (P /CVE) (Aly 2015). The central idea underpinning P/CVE is that violent extremists should not be countered exclusively by hard power but also through soft power (Frazer & Nünlist 2015). This involves tackling the structural causes of violent extremism such as lack of socioeconomic opportunities, marginalisation and discrimination, poor governance, violations of human rights and the rule of law, prolonged and unresolved conflicts and radicalisation in prisons (Club de Madrid 2017; UN Development Programme 2018; United Nations 2015b).

P/CVE strategy promotes the role of the civil society organisation (CSOs) in CT (Commonwealth Secretariat 2017; Nye 2004; Steinberg 2018). The CSOs are important to remedy certain political, economic and social factors that contribute to terrorism (Charity and Security Network 2010). Hence, CSOs comprising international nongovernmental organisations (INGOs), local nongovernmental organisations (LNGOs) and community based organisations (CBOs) alongside United Nations agencies play key roles to stabilise conflict regions (Clubb & Tapley 2018; Nwangwu & Ezeibe 2019). These CSOs, especially the INGOs, participate in P/CVE through deradicalisation and counteradicalisation in the global South, though a credibility issue persists as many INGOs receive funding for these projects from governmental institutions (Abu-Nimer 2018; Aldrich 2014; McMahon 2017; Schlegel 2019; Spalek 2016).

As the role of these INGOs in humanitarian and P/CVE programming increases, the number of INGOs increases. In 2014, there were over 20,000 INGOs globally (Penner 2014). Most of these INGOs operate in the global South, especially Africa, the domain of most humanitarian conflicts (Byman 2001; Novelli 2017; UN Economic and Social Council 2018). INGOs refers to voluntary, transnational and nonprofit organisations that set international standards for peace, security and development, hold nations accountable to these standards and provide the resources to meet the standards (Lee 2010). Independence, humanity, impartiality, neutrality and universality are the underlying principles of the INGOs (De Torrenté 2006; Duffield, Macrae & Curtis 2001), though they are often perceived as biased (Abiew 2012). This is connected to the tendency of the INGOs to promote neoliberal principles such as democracy, gender equality and human rights in the global South (Abiew 2012; Duffield, Macrae & Curtis 2001; Karlsrud 2019).

Despite the criticisms against the INGOs, their activities continue to expand, even to the shores of Nigeria where violent extremisms have continued to rear their ugly heads since the 1980s. This period witnessed the rise of the Maitasine group, a fanatic religious group that terrorised the Northern states of former Gongola, Bauchi and Kaduna (Ezeani et al. 2021). Keying into a similar ideological doctrine of Islamic fundamentalism propagated by this group, Mohammed Yusuf in 2002 founded the Jamatu Ahli Al-Sunna lil Da’wa Wal Jihad (JAS) (People committed to the propagation of the Prophet’s teaching and Jihad). To this group, Western education is forbidden (Boko Haram)—a term that has come to be the name of the sect. Boko Haram’s continued forceful and violent campaign, essentially for the abolishment of Western education and for the establishment of an Islamic state in Nigeria, brought it face to face with the Nigerian authorities, especially the military. The immensity of the dastardly activities of Boko Haram terrorists/terrorism in Nigeria has led to the promulgation of a number of ant-terrorism laws. These include the Terrorism (Prevention) Act of 2011 and the Terrorism (Prevention) (Amendment) Act of 2013, both of which seek to imprison for not less than twenty (20) years any person(s) convicted of directly or indirectly participating, supporting or sponsoring terrorism or terrorist groups in Nigeria.

Although the Nigerian military has consistently carried out military campaigns to counter the violent activities of Boko Haram in the Northeast of Nigeria and have had occasions to declare the sect ‘technically defeated’ (BBC 2015; Lenshie et al. 2021), the violent operations of the group continued to soar. This led to the realisation that military might alone is incapable of P/CVE in the Northeast of Nigeria. The existence and operation of over 36 leading INGOs alongside other CSOs for P/CVE and humanitarian programming is therefore an acknowledgement of the fact that military might needed to be complemented with non-kinetic and humanitarian ventures (Nigeria International Non-Governmental Organization Forum 2018). The major INGOs implementing P/CVE programming in Northeast Nigeria include Mercy Corps, the Centre for Human Development, Search for Common Ground, International Alert and the International Committee of Red Cross. These INGOs also operate alongside the national military, especially the Army and the Air Force, in the conflict region to improve human security (Abiew 2003; Bell et al. 2013). Meanwhile, ‘civil–military relations are complex and not always harmonious’ (Cunningham 2018). Naison Ngoma observed that ‘civil–military relations in Africa are strongly influenced by its colonial history of the military that was feared and disliked’ (Ngoma 2006). Although INGOs are transnational in character, they are deeply embedded in national context. Thus domestic institutional configurations and the nature of mandates shape their relationships with other INGOs and security agencies (Ruffa & Vennesson 2014).

While previous studies have examined the role of INGOs in transnational advocacy (Ahmed & Potter 2006), the relationships between international and local offices of INGOs (Luxon & Wong 2017) and the impact of INGO–military relations on peacekeeping operations and humanitarian programming (Abiew 2012), how INGO–military relations affect the P/CVE programming has not been central to existing academic debates. In specific terms, the study sought objective answers to the following questions: (i) In which ways do the peculiarities and dynamic natures of INGOs and those of the military affect their relations in the course of P/CVE in Northeast Nigeria? (ii) What are the drivers of the mistrust and conflict between INGOs and the military on P/CVE in Northeast Nigeria? (iii) How have this mistrust and conflict between INGOs and the military impacted the P/CVE in Northeast Nigeria?

This study probes how relations between INGOs and military actors affect preventing/countering violence extremism in Northeast Nigeria, arguing that INGO–military relations in Northeast Nigeria are largely mistrustful and or conflictive due to the variance in their operational principles. In view of this, the study focuses on unravelling the areas of conflict between these two types of actors, especially as it concerns their mutual perceptions of each other in relation to the P/CVE programming in Northeast Nigeria. It addresses the question of how the divergent operational dynamics of the INGOs and the military have sown a seed of mistrust, and how this mistrust has further undermined the P/CVE programming in Northeast Nigeria, with Bauchi, Adamawa and Yobe states in focus. Hypothesising from the foregoing, the study pursues an argument that perhaps mutual respect for the operational procedures and principles of the military and international nongovernmental organisations in the Northeast may be relevant for enhanced international nongovernmental organisation–military relations and sustainable preventing/countering violent extremism programming in Nigeria and beyond. This line of argument presents an opportunity for achieving goal 16, target 1 of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) which seeks to significantly reduce all forms of violence and related death rates everywhere (United Nations 2015a). With the foregoing dutifully providing the needed introductory/background information, the remaining parts of this study are discussed under the following themes: methodology; modelling violent and non-violent social order in INGO–military relations; nature of INGO–military relations and the impact of INGO–military relations on P/CVE in Northeast Nigeria. General conclusions relevant for enhanced INGO–military relations and reducing all forms of violence and related deaths were drawn.

Methodology and scope of the study

The empirical focus of this study is the Northeast geopolitical zone in Nigeria. The zone is one of the six geopolitical zones in Nigeria. It houses six out of the 36 federating states in Nigeria, including Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Taraba and Yobe states. Since 2002, the Northeast has been under the attacks of Boko Haram, an Islamic sect that has transformed into a terrorist group (Eji 2016; Yusuf 2013). From 2009 to 2019, Boko Haram carried out major attacks on both public and private institutions across northern Nigeria, including the United Nations office in Abuja (Oriola 2017).

Purposive sampling was employed to select three states in northeast Nigeria, including Borno, Adamawa and Yobe (BAY) states. These states are the hotbed of Boko Haram insurgency (Assessment Capacities Project 2016; Ezeani et al. 2021) and the major focus of military CT and INGOs’ P/CVE in Nigeria from 2009 to 2019. The participants in the study are 84 stakeholders involved in CT and P/CVE in BAY states. The stakeholders comprise staff /officers of United Nations agencies, INGOs and LNGOs, Nigerian military, Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) and Knifar women, a group that is made up of over 2,000 women whose husbands, children and fathers were killed or arrested by the military in Borno State, Nigeria (Olanrewaju & Nwosu 2019). We also purposively selected five leading INGOs in the BAY states that have operational presence and committed to implement P/CVE programmes in at least two of the BAY states. They include: Amnesty International, International Medical Corps, Catholic Relief Services, Christian Aid, International Rescue. For clarity, the Nigerian military is a tripod of the Nigerian Army, Nigerian Air Force and the Nigerian Navy. However, the usage of the Nigerian military in this study is limited to the activities of the Army and Air Force which mostly carry out the counterinsurgency operations in the Northeast.

To address the above questions in the light of convincing objectivity, several modalities that are consistent with the qualitative-descriptive research orientation, including the longitudinal design, were adopted for data collection and subsequent analysis. The longitudinal approach enabled the researchers to identify and measure changes in subjects’ responses at different intervals from 2017 through 2018 and 2019 to 2020. In other words, data for the study was collected during extensive fieldwork involving the researchers and six research assistants in June 2017 with return visits in January 2018, March 2019 and March 2020 to the end of validating the previous responses. The study also utilised qualitative-dominant mixed methods comprising seventeen key informant interviews (KIIs), six group interviews, field observations and reference to secondary literature. On KIIs and group interviews: To guarantee inter-rater reliability and internal consistency, a somewhat split half method was adopted by making sure that the same set of questions, divided into two, were administered to the respondents of both the KIIs and those of group interviews. Although different persons made up these two groups, the split-half method enabled the researchers to check the consistency of responses both between the two broad groups of interviewees and among the members of each group at different intervals of our repeated visits. Between seven and eleven persons participated in each group interview. Hence, a total of 42 persons participated in the group interviews in BAY states. The criteria for selection of participants in the group interviews were cognate experience with military and INGOs operations in BAY states, availability and willingness to participate in the study. English, Pidgin English and Hausa languages were used for the interviews, depending on the educational levels of the respondents. For ease of collection and analysis, the main instruments of data collection (interview schedules) were prepared in such a way that there were three sections. Each section addressed one of the three main research questions by eliciting information from the respondents (interviewees) on minor questions derived from the major research questions. Table 1 shows at a glance the three main topics of discussion corresponding to three research questions and their derivate or subsidiary question items to which the interviewees responded.

Table 1: Main Topics of Discussion and Derivate Subsidiary Question Items

|

S/N |

Topics of Discussion |

Key Questions on: |

|

1. |

Nature of INGO –military Relations in Northeast Nigeria |

Conflictive/ Mistrustful |

|

Competitive |

||

|

Cooperative |

||

|

2. |

Drivers of the mistrust and conflict between INGOs and military |

INGOs’ publication of unverified information |

|

INGOs’ exaggeration of humanitarian crisis in northeast |

||

|

INGOs’ campaign of calumny against the military |

||

|

INGOs’ criticisms of the military strategies |

||

|

INGOs’ disrespect of the military and its strategies |

||

|

INGOs’ interference with military procedures in CT |

||

|

INGOs’ enriching of themselves at the expense of civilians in North East |

||

|

Military’s accusations of INGOs spying and supporting Boko Haram |

||

|

High income and extravagant lifestyle of INGO staff |

||

|

Increased international funds for INGOs and decreasing support for the military |

||

|

Prevalence of indigenous INGO staff |

||

|

Military’s violation of human rights |

||

|

Corruption in the military |

||

|

Military’s distortions of facts about terrorism and counterterrorism |

||

|

Failure of the military to provide security for civilians, INGO staff and supplies |

||

|

3. |

Impacts of INGO – military mistrust and conflicts on P/CVE Programming |

Reports of INGOs on human rights violation by the military erodes public trust |

|

Reports of INGOs on human rights violation by the military shrinks international support base of the military |

||

|

Limits intelligence sharing between the INGOs and the military |

||

|

Promotes the restriction of INGOs to some conflict areas |

||

|

Deny and delay provision of relief materials and social services to victims of terrorism |

||

|

Trivialises the efforts of INGOs in humanitarian assistance and P/CVE |

||

|

Trivialises the efforts of the military in counterterrorism |

||

|

Emboldens the terrorists |

||

|

Increases Boko Haram attacks on military bases |

||

|

Increases Boko Haram attacks on civilians and aid workers |

||

|

Increases out of school children |

Source: Authors’ tabulation 2020

Field observations were done at Maiduguri and Monguno in Borno, Mubi and Yola in Adamawa as well as Potiskum and Damaturu in Yobe. Our field observations were conducted in two stages. First, an exploratory pilot study involving a small sample was designed. This helped the researchers in gaining insights into and ideas about the nature of the INGO–military relations in the Northeast as well as variables/issues linked to the dynamic relations. It was the information gathered at this stage that enabled the researchers to articulate the specific question items in the interview schedule. The second phase of the field observation (structured non-participant observation) ran concurrently with the KIIs and groups interviews. We already had ideas of what we were looking out for, and keenly observed and noted how they were playing out. Secondary literature was also used to collect data on INGO–military relations and the impact of the relationship on CT and P/CVE. These secondary data were helpful in corroborating the data we gathered in the field and thus constituted a veritable part of the empirical verification of our research objectives and hypotheses.

Given the peculiarities of the sources/methods of data collection and considering the complex nature of the responses, the Constant Comparative Method (CCM) was employed to identify regular repeating patterns. There therefore came the need to order and sort them according to a number of schemas to allow for constant and consistent comparison between and amongst the gathered data. First was the first order comparison. Here, data (responses from interviewees) collected during the KIIs at different intervals (visits) of different years (2017-2020) were assembled and saved in one folder. This was followed by a systematic comparison of the responses from 2017 to 2020, noting the patterns of their consistencies and otherwise. For the data collected on group interviews, the same procedure was adopted. Those of structured non-participant field observations and secondary data were similarly sorted. Under the second order comparison, results of each group (say KIIs) were compared with the results of the group interview of the same year to establish their degree of consistency for reliability of findings. The third order comparison juxtaposed the results of the triangulated data (collected via KIIs, groups interviews, field observations) for one year with the triangulated data of other years. Hence, data collected during the KIIs, group interviews and field observations were continuously compared and then related to the study context. Secondary data of analogous temper and content were used to supplement and/or corroborate the above primarily sourced data by interposing them where and when necessary. Observably, this is a logical way of testing the reliability of data (Ezeibe et al. 2019; Glaser 1965). It should be noted that the data generated from KIIs and group interviews were transcribed from Pidgin English and Hausa to English, ordered and content-analysed. Descriptive statistical tools like tables and simple percentages were also used to analyse the data. The final manuscript was subjected to member check by the authors (Ezeibe 2021; Koelsch 2013; Mbah et al. 2021) in order to enhance inter-rater reliability, credibility and validity.

Contextualising P/CVE and modelling the violent and non-violent social order of INGO–military relations

Many studies like those by Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE),[1] Peter Neumann (2017), Nehlsen et al. (2020) and Baaken et al. (2020) have examined P/CVE under various themes such as Countering Violent Extremism (CVE), Preventing Violent Extremism (PVE), Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism and Radicalization (PCVER). Despite some observable definitional and conceptual variations in their orientations, a common denominational thread that runs through their contributions is that each of these themes represents a set of strategies and approaches that aim to prevent or mitigate radical and/or violent extremism. Although pontificating from the health sciences, Gerald Caplan and Robert Gordon made very insightful efforts to categorise and explore the applications of the various categories of the prevention approach, depending on the time and character of the target population (Gordon 1983). While Gerald Caplan came up with what he listed and described as universal, selective and indicated preventions (Caplan 1964), Robert Gordon settled for what he conceives as the primary, secondary and tertiary prevention approaches (1983).

Although slightly different, Caplan’s three-phased prevention approach loosely corresponds to those of Gordon, such that we can hazard such pairings as universal/primary, selective/secondary and indicated/tertiary preventions (Caplan 1964). While the first two pairings (universal/primary and selective/secondary) are basically preemptive and targeted at preventing the development and manifestations of social disease (violent extremist tendencies) by nipping them in the bud, tertiary/indicative prevention applies to people among whom the unwanted phenomenon (extremism/violence) had become fully developed. The primary aim of the tertiary/indicative prevention is, therefore, to wean such individuals or groups from such social deviancy (extremism/violence) and to ensure that they do not go back to it later. Stricto sensu, ‘tertiary or indicated prevention describes a reactive measure tackling problems that are already manifest’ (Nehlsen et al. 2020), Implicit in this, therefore, is that countering extremism is an integral part of the tertiary or indicated prevention approach and thus can be accommodated within the theoretical adumbrations of Caplan and Gordon, among others.

Our operationalisation of P/CVE therefore agrees largely with the foregoing, noting further that the Nigerian Government’s Operation Safe Corridor (OSC) programme geared towards deradicalising, demobilising, rehabilitating and reintegrating repentant Boko Haram members falls neatly within the operational vicinity of P/CVE. Interestingly, the OPSC programme is a non-kinetic approach to P/CVE, it being coordinated by the Nigerian Military (International Crisis Group 2021). Under it, Boko Haram members are encouraged to renounce extremism and embrace normal life and get some benefits, including trainings on vocational jobs and oversea scholarships. Although the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs, Disaster Management and Social Development and the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) corroborate with the Military in the coordinating the OPSC programme, the programme itself, is a multi-agency, multi-national humanitarian operation composed of 468 staff comprising 17 Ministries, Departments and Agencies as well as other international agencies and organisations, aimed at deradicalising, rehabilitating and re-integrating repentant Boko Haram members, as part of the measures to fast track the peace process in the Northeast (Abdullateef 2020). The INGOs’ P/CVE programmes in the Northeast essentially focus on local stabilisation operations/programmes. These are programmes which fit into the broader definition of seeking to bolster legitimate state authority, reconciliation and peaceful conflict management systems, and as such centre on the following priorities:

- strengthening local-level and state-level conflict prevention and community security mechanisms to help communities prevent and solve emerging conflicts and tensions;

- rehabilitating civilian infrastructure and basic services to strengthen government legitimacy and responsiveness to citizen needs; and

- supporting the reintegration of former fighters, civilian militia and those associated with insurgent groups, as well as local-level social cohesion more broadly, with a long-term view toward social healing and reconciliation (Brechenmacher 2019).

Our conceptualisation of the P/CVE programme in this study therefore is a contrivance for the multi-jointed tasks and activities carried out (or expected to be carried out) by both the Nigerian military and the INGOs towards managing violent conflicts in the Northeast of Nigeria. In other words, there is both a soft side and a hard side to the INGO–Military coordinated P/CVE in the Northeast of Nigeria.

The existence of these two dimensions to the P/CVE in the Northeast, Nigeria finds expression in the theoretical model of Smart Power. The coinage and formulation of what has come to be Smart Power theory around 2004 have been attributed to Suzanne Nossel,[2] although Joseph Nye[3] who also claims to have invented the term in 2003 has made enormous contributions to its refinement and development. As a term, Smart Power was originally used within the field of international relations to refer to the combination of hard power and soft power strategies. By way of further elucidation, the Centre for Strategic and International Studies sees it as an approach that underscores the necessity of a strong military, but also invests heavily in alliances, partnerships and institutions of all levels to expand one’s influence and establish legitimacy of one’s action (CSIS 2007). Whereas hard power entails the deployment of and reliance on military, coercive and other aggressive means for the attainment of an end/objective, soft power focuses on the activation of diplomacy, culture and history in attaining the same (Copeland 2010). Smart Power theory/model presupposes the existence of two circles of power (hard and soft) placed side by side with a point of intersection. It is at the point of intersection that a hybrid power (smart power) emerges, embodying and combining the features of both soft power and hard power. As Michael Ugwueze and Freedom Onuoha rightly identified, the absence of soft power approach/dimension to the hard-power-dominated counter-terrorism measures has remained one of the major challenges confronting the Nigerian state in its effort to defeat Boko Haram insurgency even with military force (Ugwueze & Onuoha 2020). The Smart power model, therefore, is a hybrid of the interagency corroboration that Okechukwu Ikeanyibe et al passionately advocate for in the management of counter-insurgency campaigns against Boko Haram in Nigeria (Ikeanyibe et al. 2020). It is interesting to remark that these scholars are in agreement with Joseph Nye (2009) who argues that combating terrorism demands smart power strategy, insisting that employing only hard power or only soft power in a given situation will usually prove inadequate.

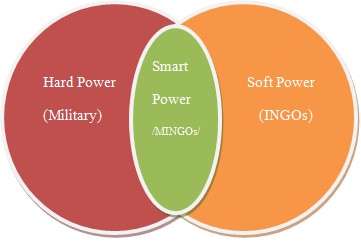

Figure 1: Diagrammatic illustration of the components of the Smart Power model

Source: Authors’ illustration

From Figure 1 above, our Smart Power Model designates the military principally as the hard power component, the INGOs as the soft power component, while MINGOs (Military/INGOs) represents the meeting point of the two circles of power—the smart power.

This model assumes that the military and INGOs frame violent and non-violent social order respectively. On the one hand, violent social orders employ forceful or coercive behaviours and symbols to guide the conduct of groups, promote human cooperation and prevent anarchy (Henslin 2001; Parguez 2016; Rodríguez-Alcázar 2017). Although social institutions with dispersed coercion (Raekstad 2018) such as international organisations could maintain order without monopoly of force, ‘only the coercive apparatus of the state (military and police) are able to provide order to large and conflicting social groups’ (Burelli 2021). The military comprising the Army, Navy and Air Force establishes violent social orders (Braun 2009) in order to protect the state in times of war, rebellion and terrorism. Often, the military are associated with human rights abuse, intimidations and aggravated assaults (Junger-Tas et al. 2010; Ramsay & Holbrook 2015).

On the other hand, non-violent social order calls into question violent social orders and seeks to create new order by opening up economic opportunities and assisting the victims of violence (Braun 2009; Mielke, Schetter & Wilde 2011). INGOs establish non-violent social order by appealing to radicalised or violent constituents to explore peaceful dialogues (Ramsay & Holbrook 2015). INGOs provide assistance to families in conflict-affected communities in the BAY states in order to promote peace (Nigeria International Non-Governmental Organization Forum 2018). For instance, while Amnesty International is involved in an advocacy campaign against human right abuse by terrorists and military in Northeast Nigeria, International Medical Corp is providing medical care for malnourished children in the region. Between 2015 and 2017, Catholic Relief Services empowered more than 8,500 people to purchase food and other household supplies (Stulman 2017). In 2018, Christian Aid fed more than 1.3 million people, supplied blankets to more than 231,000 children and constructed or rehabilitated boreholes and toilets in IDP camps in Northeast Nigeria (Christian Aid 2018). International Rescue committees have also constructed classrooms, provided books and pens for school children and trained teachers in the Northeast (International Rescue Committees 2017). Following this example, the International Committee of the Red Cross, in 2019 alone, provided more than 745,000 people with either food items or food assistance in other ways and improved access to water for over 500,000 people including household and those living in IDP camps (PRNigeria 2020). Search for Common Ground emphasises Transforming Violent Extremism and has been working towards strengthening the coalition of Human Rights in Northeast Nigeria. This approach seeks to empower communities’ ability to use non-violent means to address their grievances, support individuals who choose non-violence as an alternative, assist governments to work with other stakeholders and encourage non-violent approaches and alternative pathways to violence (Monzani & Sarota 2019).

Although the military and INGOs largely frame violent and non-violent social order respectively, there are areas of overlap and interdependence (Cuervo et al. 2018). The military is not restricted to framing violent social order. The military sometimes employ non-violent strategy to provide economic opportunities for the population in order to stabilise their dominion (Braun 2009). The overlap of INGOs’ and the military’s roles in the conflict region create relationships of cooperation, competition and conflicts. While competition and conflict occur in the absence of shared values and distinct resource bases between the actors, the combination of shared values and distinct resource bases facilitates cooperation (Johnson 2016; Nwangwu et al. 2020).

Whereas in Europe and other advanced countries of the world ‘the military is perceived as one of the most selfless and dedicated professionals in counterterrorism’ (Seiple 1996: 9), African militaries are characterised as violent, corrupt, arbitrary, immense, threatening, partisan, politicised, undisciplined, untrustworthy, unprofessional, abusive, under-funded, ill-equipped and poorly motivated (Adeakin 2016; Bappah 2016; Dala 2011; Robertson 2015). These features of the militaries in Africa are traceable to their colonial history (Clubb & Tapley 2018; Omitoogun & Oduntan 2006). Comparing the operations of Boko Haram and the military in Nigeria, the military is perceived as more violent and destructive than Boko Haram (Matfess 2017). The proliferation of cases of human rights violations by the military in Nigeria facilitates the mistrustful and conflictive relationships between the military and the stakeholders in P/CVE (Amnesty International 2018), especially the INGOs. The mistrust also promotes the military’s accusations of INGOs spying for terrorists (Nwachukwu 2018). The major implication of these mutual accusations is that it severs the relationships between them and undermines their capacities to leverage on the information, resources, alliances and networks available to each of them to promote human security (Asad & Kay 14). The next section addresses the nature of INGO–military relations in BAY states.

Nature of military-INGO relations in countering Boko Haram in BAY States

Boko Haram insurgency is a complex emergency with many aspects that no government, military, local or international organisation can handle alone. These emergencies are ambiguous and difficult for actors with different sets of interests to cooperate. The dynamic interaction and parallel existence between the INGOs in P/CVE and the military in CT generate mixed relationships. Abby Stoddard, Monica Czwarno, and Lindsay Hamsik acknowledged in their report on NGOs and Risk: Managing Uncertainty in Local-International Partnerships that issues of trust have continued to undermine INGOs and other national/local partners’ relationship in P/CVE in the Northeast of Nigeria (Stoddard, Czwarno & Hamsik 2019). Again, the creation of ministries which are also actively engaged in humanitarian activities by the Nigerian government has also led to questions about the duplication of the humanitarian roles of the INGOs. While it is the duty of the state (government) to coordinate the activities of both the ministries/agencies and the INGOs, the state seems to be wary of the activities of the latter. It is therefore not surprising that the Nigerian government has come up with a number of legislative attempts to control the activities of INGOs in Nigeria, including the June 2016 ‘Bill for an Act To Provide For The Establishment Of The Non-Governmental Organizations Regulatory Commission For The Supervision, Co-ordination And Monitoring Of Non Governmental Organizations’.

The views of Abby Stoddard, Monica Czwarno and Lindsay Hamsik are corroborative of the informed opinions of our respondents/participants. Seventeen KIIs in this study agree that ‘the interactions between the INGOs and the military create competitive, conflictive, adversarial, cooperative, mistrustful, distrustful and tensed relationships.’ Hence, Paul Carsten and Alex Akwagyiram described these relationships as fraught (Carsten & Akwagyiram 2018). Table 2 summarises the subjective views of participants on the nature of the relationships between the INGOs and the military in BAY states.

Table 2: Nature of INGO–military relations in Northeast Nigeria

|

S/N

|

Nature of relationship

|

Percentage

|

|

1

|

Conflictive/Mistrustful

|

61

|

|

2

|

Competitive

|

22

|

|

3

|

Cooperative

|

16

|

Source: Authors’ fieldwork, 2019

For clarity, a conflictive or mistrustful relationship is one that sprouts from conflict of principles. In other words, when two parties (which in this case are the military and the INGOs) find themselves equidistantly standing on the opposite sides of a spectrum of interests arising out of apparent incompatibility of principles and in turn giving rise to antagonistic relations, we speak of conflictive relations. Such relations are said to be mistrustful too because antagonistic relations, as a rule, indulge neither trust nor love. There is, however, a thin line between conflictive relations and competitive relations in the sense that most conflictive dealings usually result from competitive dealings. It is however in the place of the existence of an established rule of engagement that the former takes a radical tangential departure from the latter. The rule of engagement serves, among other things, as a restraint on the competitors from slipping suddenly into a conflictive situation. Usually, but not always, competitive relations tend to spring from the collapse of cooperative dealings. Placed side by side with goal/target attainment (P/CVE in Northeast), cooperative, competitive and conflictive relations tend to lead to higher, lesser and no goal/target attainment respectively. This is why some insights into the nature and dynamics of the relationship between and among stakeholders in P/CVE in Northeast Nigeria matters so much to the researchers.

What Table 2 above showcases, therefore, is a summary of the subjective views of participants on the nature of the relationships between the INGOs and the military in BAY states. Those percentages were arrived at through the determination of the numbers of participants in relation to their responses to questions pertaining to those qualifiers/categories (i.e., cooperative, competitive and conflictive). For instance, KII with a staff of an INGO in Maiduguri in March 2019 showed that ‘the relationship between INGOs and the military is dynamic. Frequently, cooperative and competitive relations degenerate to conflictive relations, and conflictive relations sometimes become cooperative.’ Another KII with a staff of an INGO in Maiduguri in March 2019 revealed that ‘INGO–military relations in BAY states vary from time to time and from organization to organization. INGOS that participate in education, nutrition, health, WASH are more cooperative with the military than INGOs involved in P/CVE programmes ranging from advocacy, early recovery, transportations and child and women protection.’ Hence, INGO–military collaboration is more efficient during humanitarian programming than P/CVE programming (Penner 2014). Lauren Greenwood and Gowthaman Balachandran observe that ‘the nature of the relation between one or a group of humanitarian organization(s) and the military as well as the conduct of these actors in this relationship may also have an effect on other humanitarian agencies working in the same area and even beyond’ (Greenwood & Balachandran 2014: 9).

KII with a staff of one of the INGOs in Mubi in January 2018 averred that ‘the relationship between INGOs and the military is largely conflictive. Meanwhile, this is relevant for the INGOs to protect their core values of impartiality and independence in the region.’ Indeed, ‘the underlying tension between the INGOs and military actors is as a result of their different world views, identities, interests, and organizational cultures’ (Goodhand & Sedra 2013: 273). Daniel Byman observes that the preservation of these core values is essential for the survival of NGOs in conflict and post conflict emergencies (Byman 2001). While Nicholas de Torrente observes that the coordination of humanitarian NGOs and the military in conflict situations compromises the security function of the former and the independence of the latter (De Torrenté 2006), ‘working separately in an uncoordinated manner is likely to undermine the efforts of each other with substantial implications for bringing about peace in divided societies’ (Abiew 2003: 36). Thus INGOs prefer to operate independently of the military in order to uphold their core values, they sometimes use military escorts in Borno State, where security risks are very high (Carsten & Akwagyiram 2018; Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa 2019).

The point is that the military, by the nature of their training and orientation, tend to see Boko Haram/extremist groups as an eternal enemy that must be crushed and decimated, whereas the INGOs are usually inclined towards giving considerations to such drivers of extremism like socio-economic, cultural and historical antecedents. As such, the INGOs are usually found attending to such issues that border on humanitarian and local stabilisations. These differential perceptions and treatments of extremists are fertile grounds for the eruption of tension between the military and the INGOs.

Drivers of the mistrust and conflict between military and INGOs in BAY states

There are multidimensional factors that fuel the mistrust and conflicts between INGOs and the military in BAY states. Table 3 summarises the views of the participants of the group interviews on the major drivers of the mistrust and conflict between INGOs and the military in BAY states.

Table 3: Drivers of the mistrust and conflict between INGOs and military

|

S/N |

Remarks |

Frequency in % |

|

1 |

INGOs’ publication of unverified information |

46 |

|

2 |

INGOs’ exaggeration of humanitarian crisis in North East |

55 |

|

3 |

INGOs’ campaign of calumny against the military |

49 |

|

4 |

INGOs’ criticisms of the military strategies |

64 |

|

5 |

INGOs’ disrespect of the military and its strategies |

46 |

|

6 |

INGOs’ interference with military procedures in CT |

61 |

|

7 |

INGOs’ enriching of themselves at the expense of civilians in North East |

51 |

|

8 |

Military’s accusations of INGOs spying and supporting Boko Haram |

58 |

|

9 |

High income and extravagant lifestyle of INGO staff |

46 |

|

10 |

Increased international funds for INGOs and decreasing support for the military |

48 |

|

11 |

Prevalence of indigenous INGO staff |

60 |

|

12 |

Military’s violation of human rights |

54 |

|

13 |

Corruption in the military |

47 |

|

14 |

Military’s distortions of facts about terrorism and counterterrorism |

45 |

|

15 |

Failure of the military to provide security for civilians, INGO staff and supplies |

51 |

Source: Authors’ fieldwork, 2019

Table 3 catalogues the issue areas around which military–INGO mutual mistrust and conflict tend to centre as well as the graduated responses of our participants. It shows, among other things, that INGOs’ criticisms of the military strategies and INGOs’ interference with military procedures in CT are among the major issues that the military frowns on concerning the operations of the INGOs in the Northeast. Similarly, the failure of the military to provide security for civilians, INGO staff and supplies as well as the military’s violation of human rights are among the cardinal issue areas that the INGOs feel bad about concerning the activities of the military in P/CVE in the Northeast of Nigeria. KIIs with all the staff of the INGOs across the BAY states in June 2017, January 2018 and March 2019 show that human rights violations by the military is the most decisive factor which sever INGO–military relations in the region. Amnesty International reports that ‘in response to threats by the armed group Boko Haram and its ongoing commission of war crimes, security forces in Cameroon and Nigeria continued to commit gross human rights violations and crimes under international law’ (Amnesty International 2018: 21). At least 1,200 people have been killed extra-judicially by the military in its operations in BAY states as of 2015 (Amnesty International 2015). However, the reports of military violation of human rights in Nigeria are not peculiar to the Northeast zone. Other cases of human rights violations by the Nigerian military abound. Some of the obvious instances include the extra-judicial killings in Odi in Bayelsa state and ZakiBiam in Benue state in 1999 and 2001 respectively. The military have also involved in arbitrary arrests, detentions and extra-judicial killings of members of a separatist organisation known as Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) in South East Nigeria between 2017 and 2018 (Amnesty International 2018).

The recurrence of allegations and incidences of human rights violations by the Nigerian military derives from a false claim of military superiority to civilians in Nigeria. This is traceable to Nigeria’s colonial history and reinforced by the long years of military rule in Nigeria. The return of constitutional democracy in 1999 has had limited impact on the conduct of military personnel in the management of civil affairs (Ezeibe 2012). According to International Crisis Group, ‘increased involvement of the military in human rights violation alienates them from the people and deny them access to community intelligence it needs to conduct internal security operations efficiently’ (International Crisis Group 2016: 17). Furthermore, the involvement of the Nigerian military in human rights violations hampers their relationship with the governments and militaries of advanced democracies, especially the United States, which is the largest donor country for humanitarian assistance for combating insurgency (Ibekwe 2014; U.S. Mission Nigeria 2018).

Again, mutual suspicion between the INGOs and the military severe their relationships. KII with a troop commander in Mongunoin in March 2019 shows that ‘the military has a strong reason to believe that the INGOs and the LNGOs are providing intelligence and supplies for Boko Haram terrorists.’ In 2018, a member of Nigeria’s House of Representatives accused INGOs of aiding Boko Haram by providing intelligence, medications and other supplies to them (Ayitogo 2018). KII with a staff of an INGO in March 2019 revealed that ‘the military often conflate perpetrators and victims of terrorism as well as humanitarian-based and P/CVE-based INGOs. Thus, whenever P/CVE-based INGO provides services for people in conflict affected communities, where suspected Boko Haram members may inhabit; the military will accuse them of aiding and supporting terrorists. Meanwhile, INGOs ought not to be discriminatory in order to enhance their access to everyone in need of assistance.’

KII with a troop commander in Maiduguri in January 2018 notes that ‘Some INGOs are just making unnecessary troubles with the military instead of utilising the huge resources at their disposal to help the poor. Irrespective of the progress we have made in stabilising the Northeast, most INGOs are reporting poor comportment of the military and pervasive human rights abuse to justify the funds flowing to them from the international community instead of the local organisations that have the structure to reach the real people in need’. Despite the huge funds available to INGOs in BAY states, they are largely underperforming in P/CVE (Haruna 2017).

Although UNSCR 2250 highlighted the need to engage and invest in youth and women as partners in preventing conflict and pursuing peace (Williams, Walsh Taza & Prelis 2016), KII with one of the troop commanders in Yola in June 2018 pointed out that ‘the tendency of the INGO staff to enrich themselves instead of restoring and reintegrating dislocated youths and women in Northeast brews tension among stakeholders, especially between INGO and LNGOs as well as INGOs and the military.’ Meanwhile, INGOs often conduct trauma counseling workshops for young people and internally displaced people to facilitate their healing and ability to forgive (Frank & van Zyl 2018). KII with a staff of an INGO in March 2019, argued that ‘the interventions of INGOs are not concentrated on restoring already radicalized youth. They also carry out comprehensive and inclusive economic empowerment programmes for people who have not involved in violent extremism in order to ensure that they do not cross the line of peace. In fact, INGOs often create small-scale business initiatives to engage the people and or facilitate economic recovery to improve the access of youth and women to economic livelihoods.’

Field observations reveal that the military, especially the army, perceives the values and principles of other stakeholders as a threat to counterterrorism. Hence, they often seek to subordinate the roles of other stakeholders, especially the INGOs and United Nations agencies in Northeast Nigeria. A troop commander emphasised that ‘military is the most critical stakeholder in the management of Boko Haram in Nigeria, the police and other law enforcement officers are secondary actors. These secondary actors ought to play by our rules in order to be effective in the management of insurgency’ (KII with a troop commander in Maiduguri in June 2017). Meanwhile, INGOs can only play a complementary role to the military. KII with a staff of one of the INGOs in March 2019 showed that ‘the mandate of INGOs guarantees only a complementary relationship with the military. It is unprofessional for the military to subordinate INGOs like other security agencies such as the police and the CJTF.’ Hence, Chris Seiple observed that the military cannot assume, assert and act in control of INGOs that play different roles from security agencies (Seiple 1996). KII with a staff of one of the INGOs in March 2020, argued that ‘securitization of INGOs by the military frustrates collaborative approach. It also undermines dialogue among stakeholders and the effectiveness of peacebuilding approach in P/CVE.’

Again, the principle of neutrality forbids the INGOs, especially in their international humanitarian actions, from coordinating such assistance and interventions with the state security actors (the military inclusive) (UN Development Programme 2021). The same principle also forbids them (the INGOs) from reporting to them and/or accepting their escorts. Whatever the rationale for this style of neutrality, it has its own pitfalls. First, in a terrain where insurgents’ attacks on the military has intensified in guerrilla fashion, expecting the military to be less bothered about unchecked movements in the name of coordinating humanitarian assistance and interventions is less likely.

Impact of military–INGO relations on preventing/countering violent extremism

The impact of INGO–military relations on P/CVE are widespread. The UNDP blames the prolongation of the Boko Haram crisis on the conflict and mistrust between the CSO (NGOs and INGOs) and the military. Their inability to synergise has given the insurgents the leeway to enjoy a field’s day, by smartly appropriating the gap to endear themselves to the local populations who soon become willing recruits to their folds. This conflict and mistrust has also resulted in the inability of the humanitarians to provide much-needed relief services to vulnerable civilian populations.

Table 4 summarises the views of participants on the impact of the mistrust and conflicts between the INGOs and the military on P/CVE in BAY states.

Table 4: Impacts of INGO–military mistrust and conflicts on P/CVE Programming

|

S/N |

Remarks |

Frequency in % |

|

1 |

Reports of INGOs on human rights violation by the military erodes public trust |

88 |

|

2 |

Reports of INGOs on human rights violation by the military shrinks international support base of the military |

75 |

|

3 |

Limits intelligence sharing between the INGOs and the military |

95 |

|

4 |

Promotes the restriction of INGOs to some conflict areas |

92 |

|

5 |

Deny and delay provision of relief materials and social services to victims of terrorism |

74 |

|

6 |

Trivialises the efforts of INGOs in humanitarian assistance and P/CVE |

78 |

|

7 |

Trivialises the efforts of the military in counterterrorism |

81 |

|

8 |

Emboldens the terrorists |

91 |

|

9 |

Increases Boko Haram attacks on military bases |

71 |

|

10 |

Increases Boko Haram attacks on civilians and aid workers |

56 |

|

11 |

Increases out of school children |

52 |

Source: Authors’ fieldwork, 2019

The table shows in percentage degree the cumulative consequences of the inability of the military and the INGOs to collaborate well in P/CVE in Northeast Nigeria. Among other things, the mistrust and conflict have limited intelligence sharing between the INGOs and the military culminating dangerously to increase in Boko Haram attacks on civilians, aid workers and the military themselves, etc. KII with a troop commander in Maiduguri in March 2019 reveals that ‘the reports of INGOs on human rights abuse by the military in BAY states damage the local and international reputation of the military, erodes public trust of the military and hampers the supports from militaries of developed countries and their governments.’ This view is in sync with the UNDP report of 2021 which holds that the military’s blanket accusations, arbitrary arrests and civilian detentions created an atmosphere of fear among communities and a deep resentment towards security forces (UN Development Programme 2021).

While the non-violent nature of NGOs makes them civilian-friendly and gives them access to intelligence, the military orientation makes it difficult to access information (Byman 2001; Smith 2010). Meanwhile, collaboration between the key national and international actors that operate in conflict areas such as Kenya, Somalia and South Sudan improved the capacity of civil society organisations to deliver on P/CVE programming unlike in Northeast Nigeria, where poor collaboration between INGOs and the military is re-escalating terrorist attacks. KII with a staff of an INGO in Maiduguri in March 2020 remarks that ‘Poor collaboration between the key national and international actors that operate in the counterterrorism theater frustrates P/CVE programming, especially, efforts of INGOs to promote criminal justice, rule of law, community resilience and financial inclusion. It also undermines counterterrorism efforts in the region.’ Human Rights First noted that the tendency of the Nigerian security agencies, especially the military, to apply force, silence dissenting voices, violate human rights and attack civil society organisations and human rights defenders is not only reversing the gains of P/CVE but fomenting extremism in the Northeast region. Meanwhile, this is not peculiar to Nigeria. The government and security agencies of Bahrain, Egypt, Kenya, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have also been involved in stifling peaceful dissent, muzzling the media and preventing legitimate activities of non-violent civil society organisations (Human Rights First 2015).

Although the Nigerian military recorded a huge success in degrading the territorial control of Boko Haram from 2015 to 2016, the attacks by the group on military bases increased from 2017 to 2019 (Brechenmacher 2019). In 2018, Boko Haram overran 14 out of 20 military bases in northern and central Borno and killed over 1000 soldiers. This figure excludes soldiers killed in Yobe, Adamawa and Southern Borno (Salkida 2019). The increasing Boko Haram attacks have not only led to loss of soldiers, it also leads to loss of costly weapons. The Nigerian Air Force and the Nigerian Army lost over N4.8bn worth of military weapons in between January and May 2019 (Aluko 2019).

Sustained Boko Haram attacks have also heightened the fatalities of aid workers in Nigeria from only one in 1997 to more than 400 in 2016 (Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa 2019; Oladimeji 2016). Boko Haram terrorists have killed over 27,000 people and displaced over 1.8 million with 7.7 million people in need (International Crisis Group 2019; UN High Commissioner for Refugees 2019). The conflict has also destroyed over 1500 schools, killed over 2,295 teachers, displaced over 19,000 teachers and kidnapped more than 4000 persons, especially school girls in BAY states (Aluko 2018). KII with the leader of CJTF in Maiduguri in March 2019 shows that ‘limited civil–military cooperation fuels Boko Haram attacks on schools and increases the number of out of school children in BAY states’. The number of out-of-school children in Nigeria increased from 10.5 million in 2017 to 13.3 million in 2018. Hence, Nigeria accounts for 45% of out-of-school children in West Africa and 69% of the children are in Northern states (Lawal 2018). The military’s inability to protect civilians from Boko Haram terrorists generated widespread resentment of the military. It also led to communities’ accusation of security forces collaborating with the insurgents, and prolonging the fighting for financial gain (Brechenmacher 2019).

Despite the escalation of Boko Haram attacks and increase in the number of terrorist victims in BAY states, the military restricts INGOs from accessing Guzamala, Abadam, Marte, Kukawa, KwayaKusar, Shani, Bayo local governments in Borno (UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs 2019). The military use a counterterrorism agenda to justify these restrictions, arguing that they are unable to guarantee the safety of staff (Norwegian Refugee Council 2018). KII with a troop commander in Monguno in June 2018 reveals that the ‘military’s restriction of INGOs from accessing these conflict areas is as a result of our suspicions that INGOs are providing supplies and spying for Boko Haram terrorists’. Between 2018 and 2019, the Nigerian military accused United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Mercy Corps, Action Against Hunger and Amnesty International of engaging in clandestine activities that undermine counterterrorism operations in Northeast Nigeria. They also suspended these organisations, though the suspension was later reversed (Njoku 2020).

These restrictions and suspensions promote the inaccessibility of the INGOs to the conflict affected areas as well as prevent them from providing relief materials and supporting community resilience, peacebuilding and P/CVE programming. This leaves an estimated 3 million people at risk of hunger in the BAY states (Daily Trust 2018; UN High Commissioner for Refugees 2017). It also generates poor child health outcomes in the resource poor area (Dunn 2018). In fact, strict control of Borno by the military undermines the capacity of the INGOs to provide services ranging from coordination and management of displaced persons’ camps, education, early recovery, emergency telecommunications, food security, health, transportations, nutrition, protection and shelter to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH). Significantly, ‘the restriction of INGOs from accessing some of the conflict areas hampers the participation of other CSOs in P/CVE’ (KII with a staff of INGO in Maiduguri, March 2019). Thus this ‘increases the vulnerability of women and children in BAY states’ (KII with a staff of an INGO in Damaturu, January 2018). Perhaps relaxing these restrictions of access of INGOs to conflict areas is relevant for enhancing the role of INGOs in P/CVE (International Crisis Group Asia 2019).

Conclusion

The article argues that INGO–military relations is a critical aspect of civil–military relations, although the Nigerian experience has so far proven to be fraught, largely mistrustful and conflictive. The major factor driving these mistrustful and conflictive INGO–military relations in the BAY states is mutual suspicion and dynamics of operations. While the INGOs argue that the military’s violation of human rights, corruption, accusation that INGOs are spying for Boko Haram and the failure to secure citizens, INGOs’ staff and relief material weakens INGO–military relations, the military on the other hand contends that INGOs’ publication of unverified information, exaggeration of humanitarian crisis, campaign of calumny against the military, disrespect of military strategies and procedures in counterterrorism are the major sources of the tension between the INGOs and the military in the Northeast region.

This mutual suspicion between the INGOs and the military is counterproductive for P/CVE programming in BAY states. It erodes public trust of the military, shrinks the international support base of the military, limits intelligence sharing between the INGOs and the military, restricts the INGOs to some conflict areas, delays the speed of delivery of relief materials and social services to victims of terrorism and increases Boko Haram attacks on civilians, military bases and aid workers and heightens the level of vulnerability of women and children. It undermines the capacity of INGOs to build sustainable societies and reverses the gains of the military in counterterrorism. The paper concludes that mutual respect for the operational procedures and principles of the military and international nongovernmental organisations in the Northeast is relevant for enhanced international nongovernmental organisation–military relations and sustainable preventing/countering violent extremism programming in Northeast Nigeria and beyond.

***

Christian Ezeibe is a Senior Lecturer with the Department of Political Science and a Senior Research Fellow with, Institute of Climate Change Studies Energy and Environment in the University of Nigeria Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria

Nnamdi Mbaigbo is with the Department of Public Administration, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. He is also the Founder of Tropicalgate Foundation for Sustainable Development, Lagos Nigeria.

Nneka Okafor is a Senior Lecturer with the Department of Philosophy, University of Nigeria Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria.

Celestine Udeogu is a Lecturer with the Department of Political Science, University of Nigeria Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria.

Adolphus Uzodigwe is a Research Fellow and Lecturer with the Institute of African Studies, University of Nigeria Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria.

Usman S Ogbo is a Senior Lecturer with Department of Political Science, Kogi State University, Anyigba, Kogi State, Nigeria.

Chika Oguonu is a Professor with the Department of Public Administration, University of Nigeria, Nsukka.

Funding

We appreciate Tropical Gate Foundation, Lagos for funding this research under grant number TGF0002-202.

Acknowledgement

We also acknowledge the participants in this study as well as the editors of CEJISS.

References

Abdullateef, I. (2020): Ministry to Collaborate with Operation Safe Corridor to End Insecurity in the North-East, 20 February, <accessed online: https://fmic.gov.ng/ministry-to-collaborate-with-operation-safe-corridor-to-end-insecurity-in-the-north-east/>.

Abiew, F. K. (2003): NGO-Military Relations in Peace Operations. International Peacekeeping, 10(1), 24–39.

Abiew, F. K. (2012): Humanitarian Action under Fire: Reflections on the Role of NGOs in Conflict and Post-Conflict Situations. International Peacekeeping, 19(2), 203–216.

Abu-Nimer, M. (2018): Alternative Approaches to Transforming Violent Extremism: The Case of Islamic Peace and Interreligious Peacebuilding. In: Austin, B. & Giessmann, H.-J. (eds.): Transformative Approaches to Violent Extremism. Berlin: Berghof Foundation, 1–20.

Adeakin, I. (2016): The Military and Human Rights Violations in Post-1999 Nigeria: Assessing the Problems and Prospects of Effective Internal Enforcement in an Era of Insecurity. African Security Review, 25(2), 129–145.

Ahmed, S. & Potter, D. (2006): NGOs in International Politics. Bloomfield: Kumarian Press.

Aldrich, D. P. (2014): First Steps Towards Hearts and Minds? USAID’s Countering Violent Extremism Policies in Africa. Terrorism and Political Violence, 26(3), 523–546.

Aluko, O. (2018): 1,500 Schools Destroyed by Boko Haram in North-East – FG. Punch, 4 May, <accessed online: https://punchng.com/1500-schools-destroyed-by-bharam-in-north-east-fg/>.

Aluko, O. (2019): Military Loses N4.8bn Weapons in North-East since January. Punch, 26 May, <accessed online: https://punchng.com/military-loses-n4-8bn-weapons-in-north-east-since-january>.

Aly, A. (2015): Finding Meaning for Countering Violent Extremism. Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism, 10(1), 1–2.

Amnesty International (2015): Stars on the Shoulder, Blood on Their Hands: War Crimes Committed by the Nigeria Military. Amnesty International, <accessed online: https://www.amnesty.org.uk/files/webfm/Documents/issues/afr4416572015english.pdf>.

Amnesty International (2018): Amnesty International Report 2017/18: The State of the World’s Human Rights. Amnesty International.

Asad, A. L. & Kay, T. (14): Theorizing the Relationship between NGOs and the State in Medical Humanitarian Development Projects. Social Science & Medicine, 120, 325–333.

Assessment Capacities Project (2016): North-East Nigeria Conflict. ACAPS Crisis Profile Nigeria, <accessed online: https://www.acaps.org/sites/acaps/files/products/files/160712_acaps_cri sis_profile_northeast_nigeria_b.pdf>.

Ayitogo, N. (2018): Lawmaker Accuses NGOs of Aiding Boko Haram. Premium Times, 30 November, <accessed online: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/more-news/298328-video-lawmaker-accuses-ngos-of-aiding-boko-haram.html>.

Baaken, T., Korn, J., Ruf, M. & Walkenhorst, D. (2020): Dissecting Deradicalization: Challenges for Theory and Practice in Germany. International Journal of Conflict and Violence (IJCV), 14(2), 1–18.

Bappah, H. Y. (2016): Nigeria’s Military Failure against the Boko Haram Insurgency. African Security Review, 25(2), 146–158.

BBC (2015): Nigeria Boko Haram: Militants ‘Technically Defeated’ - Buhari. BBC News, 24 December, <accessed online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-35173618>.

Bell, S. R., Murdie, A., Blocksome, P. & Brown, K. (2013): ‘Force Multipliers’: Conditional Effectiveness of Military and INGO Human Security Interventions. Journal of Human Rights, 12(4), 397–422.

Braun, N.-C. (2009): Displacing, Returning, and Pilgrimaging: The Construction of Social Orders of Violence and Non-Violence in Colombia. Civil Wars, 11(4), 455–476.

Brechenmacher, S. (2019): Stabilizing Northeast Nigeria After Boko Haram. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Burelli, C. (2021): A Realistic Conception of Politics: Conflict, Order and Political Realism. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 24(7), 977–999.

Byman, D. (2001): Uncertain Partners: NGOs and the Military. Survival, 43(2), 97–114.

Caplan, G. (1964): Principles of Preventive Psychiatry. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Carsten, P. & Akwagyiram, A. (2018): Killing of Aid Workers in Nigeria a Setback for Troubled Crisis Response. Reuters, 22 March, <accessed online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-nigeria-security-idUSKBN1GY0LN>.

Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa (2019): Supporting Humanitarian Workers in North-Eastern Nigeria, 13 June, <accessed online: https://cseaafrica.org/supporting-humanitarian-workers-in-north-eastern-nigeria/>.

Charity and Security Network (2010): State and Defense Officials to Senate: Military Alone Cannot Counter Violent Extremism, 31 March, <accessed online: https://charityandsecurity.org/archive/state_and_defense_to_senate_military_alone_cannot_counter_violent_extremism/>.

Christian Aid (2018): Humanitarian Response in Northeast Nigeria. Christian Aid, <accessed online: https://www.christianaid.org.uk/about-us/programmes/north-east-nigeria-humanitarian-response>.

Club de Madrid (2017): Preventing Violent Extremism in Nigeria: Effective Narratives and Messaging (National Workshop Repor). Club de Madrid, 24 May, <accessed online: http://www.clubmadrid.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/2.-Nigeria_Report.pdf>.

Clubb, G. & Tapley, M. (2018): Conceptualising De-Radicalisation and Former Combatant Re-Integration in Nigeria. Third World Quarterly, 39(11), 2053–2068.

Commonwealth Secretariat (2017): Building on ‘Civil Paths to Peace’ as a Model for Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) in the Commonwealth. Commonwealth Law Bulletin, 43(3–4), 438–455.

Copeland, D. (2010): Hard Power Vs. Soft Power. The Mark, 2 February.

CSIS (2007): CSIS Commission on Smart Power: A Smarter, More Secure America. Center for Strategic & International Studies, <accessed online: https://carnegieendowment.org/files/csissmartpowerreport.pdf>.

Cuervo, K., Villanueva, L., Born, M. & Gavray, C. (2018): Analysis of Violent and Non-Violent Versatility in Self-Reported Juvenile Delinquency. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 25(1), 72–85.

Cunningham, A. J. (2018): International Humanitarian NGOs and State Relations: Politics, Principles and Identity. London, New York: Routledge.

Daily Trust (2018): International NGOs Committed to Northeast Humanitarian Response. Daily Trust, 8 February, <accessed online: https://dailytrust.com/international-ngos-committed-to-northeast-humanitarian-response>.

Dala, M. (2011): Defence Transformation: Challenges for the Nigerian Military. In: Mbachu, O. & Sokoto, A. (eds.): Nigerian Defence and Security: Policies and Strategies. Kaduna: Medusa Academic Publishers Limited.

De Torrenté, N. (2006): Humanitarian NGOs Must Not Ally with Military. Doctors without Borders, 1 May, <accessed online: https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/what-we-do/news-stories/research/humanitarian-ngos-must-not-ally-military>.

Duffield, M., Macrae, J. & Curtis, D. (2001): Editorial: Politics and Humanitarian Aid. Disasters, 25(4), 269–274.

Dunn, G. (2018): The Impact of the Boko Haram Insurgency in Northeast Nigeria on Childhood Wasting: A Double-Difference Study. Conflict and Health, 12(6), 1–12.

Duyvesteyn, I. (2008): Great Expectations: The Use of Armed Force to Combat Terrorism. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 19(3), 328–351.

Eji, E. (2016): Rethinking Nigeria’s Counter-Terrorism Strategy. The International Journal of Intelligence, Security, and Public Affairs, 18(3), 198–220.

Ezeani, E. O., Ani, C. K., Ezeibe, C. & Ubiebi, K. (2021): From a Religious Sect to a Terrorist Group: The Military and Boko Haram in Northeast Nigeria. African Renaissance, 18(2), 125–145.

Ezeibe, C. (2021): Hate Speech and Election Violence in Nigeria. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 56(4), 919–935.

Ezeibe, C. C. (2012): Military Interventions in French West Africa and Economic Community of West African States. African Renaissance, 9(2), 95–108.

Ezeibe, C., Ilo, C., Oguonu, C., Ali, A., Abada, I., Ezeibe, E., Oguonu, C., Abada, F., Izueke, E. & Agbo, H. (2019): The Impact of Traffic Sign Deficit on Road Traffic Accidents in Nigeria. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion, 26(1), 3–11.

Frank, C. & van Zyl, I. (2018): Preventing Extremism in West and Central Africa Lessons from Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Mali, Niger and Nigeria. Institute for Security Studies, 28 September, <accessed online: https://www.africaportal.org/publications/preventing-extremism-west-and-central-africa-lessons-burkina-faso-cameroon-chad-mali-niger-and-nigeria/>.

Frazer, O. & Nünlist, C. (2015): The Concept of Countering Violent Extremism. CSS Analyses in Security Policy, No. 183, <accessed online: https://css.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/pdfs/CSSAnalyse183-EN.pdf>.

Glaser, B. G. (1965): The Constant Comparative Method of Qualitative Analysis. Social Problems, 12(4), 436–445.

Goodhand, J. & Sedra, M. (2013): Rethinking Liberal Peacebuilding, Statebuilding and Transition in Afghanistan: An Introduction. Central Asian Survey, 32(3), 239–254.

Gordon, R. S. (1983): An Operational Classification of Disease Prevention. Public Health Reports, 98(2), 107–109.

Greenwood, L. & Balachandran, G. (2014): The Search for Common Ground Civil–Military Relations in Pakistan. London: Overseas Development Institute.

Haruna, A. (2017): Boko Haram: Borno Governor Lambasts UNICEF, 126 Other ‘Nonperforming’ NGOs. Premium Times, 11 January, <accessed online: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/220082-boko-haram-borno-governor-lambasts-unicef-126-nonperforming-ngos.html>.

Henslin, J. M. (2001): Down to Earth Sociology. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Human Rights First (2015): The Role of Human Rights in Countering Violent Extremism: A Compilation of Blueprints for U.S. Government Policy. Human Rights First, <accessed online: https://www.humanrightsfirst.org/sites/default/files/Human-Rights-CVE-compilation.pdf>.

Ibekwe, N. (2014): America Replies Nigeria, Releases Details of Aid to Nigerian Military in War against Boko Haram. Premium Times, 14 November, <accessed online: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/171127-america-replies-nigeria-releases-details-aid-nigerian-military-war-boko-haram.html>.

Ikeanyibe, O. M., Olise, C. N., Abdulrouf, I. & Emeh, I. (2020): Interagency Collaboration and the Management of Counter-Insurgency Campaigns against Boko Haram in Nigeria. Security Journal, 33(3), 455–475.

International Crisis Group (2016): Nigeria: The Challenge of Military Reform. International Crisis Group, 6 June, <accessed online: https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/nigeria-challenge-military-reform>.

International Crisis Group (2019): Facing the Challenge of the Islamic State in West Africa Province Africa. International Crisis Group, 16 May, <accessed online: https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/273-facing-the-challenge.pdf>.

International Crisis Group (2021): An Exit from Boko Haram? Assessing Nigeria’s Operation Safe Corridor. International Crisis Group, 19 February, <accessed online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/An%20Exit%20from%20Boko%20Haram_%20Assessing%20Nigeria%E2%80%99s%20Operation%20Safe%20Corridor%20_%20Crisis%20Group.pdf>.

International Crisis Group Asia (2019): An Opening for Internally Displaced Person Returns in Northern Myanmar. International Crisis Group Asia, 22 May, <accessed online: https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/B156%20An%20Opening%20for%20IDPS%20web.pdf>.

International Rescue Committees (2017): Nigeria: Fighting Back with Education. International Rescue Committees, <accessed online: https://www.rescue.org/article/nigeria-fighting-back-education>.

Johnson, T. (2016): Cooperation, Co-Optation, Competition, Conflict: International Bureaucracies and Non-Governmental Organizations in an Interdependent World. Review of International Political Economy, 23(5), 737–767.

Junger-Tas, J., Marshall, I. H., Enzmann, D., Killias, M., Steketee, M. & Gruszczynska, B. (eds.) (2010): Juvenile Delinquency in Europe and Beyond: Results of the Second International Self-Report Delinquency Study. London: Springer.

Karlsrud, J. (2019): From Liberal Peacebuilding to Stabilization and Counterterrorism. International Peacekeeping, 26(1), 1–21.

Koelsch, L. E. (2013): Reconceptualizing the Member Check Interview. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 12(1), 168–179.

Lawal, I. (2018): Nigeria Accounts for 45% Out-of-School Children in West Africa, Says UNICEF. The Guardian, 29 October, <accessed online: https://guardian.ng/news/nigeria-accounts-for-45-out-of-school-children-in-west-africa-says-unicef/>.

Lee, T. (2010): The Rise of International Nongovernmental Organizations: A Top-Down or Bottom-Up Explanation? Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 21(3), 393–416.

Lenshie, N. E., Okengwu, K., Ogbonna, C. N. & Ezeibe, C. (2021): Desertification, Migration, and Herder-Farmer Conflicts in Nigeria: Rethinking the Ungoverned Spaces Thesis. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 32(8), 1221–1251.

Luxon, E. M. & Wong, W. H. (2017): Agenda-Setting in Greenpeace and Amnesty: The Limits of Centralisation in International NGOs. Global Society, 31(4), 479–509.

Matfess, H. (2017): In Partnering With Nigeria’s Abusive Military, the U.S. Is Giving Boko Haram a Lifeline. World Politics Review, 24 October, <accessed online: https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/23447/in-partnering-with-nigeria-s-abusive-military-the-u-s-is-giving-boko-haram-a-lifeline>.

Mbah, P. O., Iwuamadi, K. C., Udeoji, E., Eze, M. & Ezeibe, C. C. (2021): Exiles in Their Region: Pastoralist-Farmer Conflict and Population Displacements in North Central, Nigeria. African Population Studies, 35(1).

McMahon, P. C. (2017): The NGO Game: Post-Conflict Peacebuilding in the Balkans and Beyond. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Mielke, K., Schetter, C. & Wilde, A. (2011): Dimensions of Social Order: Empirical Fact, Analytical Framework and Boundary Concept. Bonn: Center for Development Research.

Monzani, B. & Sarota, A. (2019): Using Peacebuilding to Counter Violent Extremism: Lessons from Kenya and Tanzania. Agency for Peacebuilding, 30 April, <accessed online: https://www.peaceagency.org/using-peacebuilding-to-counter-violent-extremism-lessons-from-kenya-and-tanzania/>.

Nehlsen, I., Biene, J., Coester, M., Greuel, F., Milbradt, B. & Armborst, A. (2020): Evident and Effective? The Challenges, Potentials and Limitations of Evaluation Research on Preventing Violent Extremism. International Journal of Conflict and Violence (IJCV), 14(2), 1–20.

Neumann, P. R. (2017): Countering Violent Extremism and Radicalisation That Lead to Terrorism: Ideas, Recommendations, and Good Practices from the OSCE Region, 28 September, <accessed online: http://www.osce.org/chairmanship/346841?download=true>.

Ngoma, N. (2006): Civil-Military Relations in Africa: Navigating Uncharted Waters. African Security Review, 15(4), 98–111.

Nigeria International Non-Governmental Organization Forum (2018): Nigeria: Humanitarian Response Plan, 2018. Action Against Hunger, 8 February, <accessed online: https://www.actionagainsthunger.org/story/nigeria-humanitarian-response-plan-2018>.

Njoku, E. T. (2020): Investigating the Intersections between Counter-Terrorism and NGOs in Nigeria: Development Practice in Conflict-Affected Areas. Development in Practice, 30(4), 501–512.

Norwegian Refugee Council (2018): Principles under Pressure: The Impact of Counterterrorism Measures and Preventing/Countering Violent Extremism on Principled Humanitarian Action. Norwegian Refugee Council, <accessed online: https://www.nrc.no/globalassets/pdf/reports/principles-under-pressure/1nrc-principles_under_pressure-report-screen.pdf>.

Nossel, S. (2004): Smart Power. Foreign Affairs, 83(2), 131–142.

Novelli, M. (2017): Education and Countering Violent Extremism: Western Logics from South to North? Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 47(6), 835–851.

Nwachukwu, O. (2018): Nigerian Military Suspends UNICEF Activities in North East. PRNigeria News, 14 December, <accessed online: https://prnigeria.com/2018/12/14/military-suspends-unicef-northeast/>.