Abstract

In our research, we focus on the image of the United States in Latin America. We use mainly data from Latinobarómetro, and we analyse Obama’s last year and Trump’s first year in the presidency in 18 countries in Latin America. We use logistic regression to reach conclusions. We also analyse Trump’s tweets to see his Twitter rhetoric. We find that Trump’s election has strongly worsened the image of the United States in the public opinion of Latin America. However, we find that people that believe more in democracy, the free market and national political institutions are more likely to have a positive opinion of the United States. Also, we find that the more left-wing citizens are, the more likely they have a bad opinion of the United States. This article contributes to the theory of trust and research on the public opinion across nations. Also, this article offers insights into the topical research agenda concerning the influence of political ideology on public opinion.

Keywords

‘I will build a great wall - and no one builds walls better than me, believe me - and I will build them very inexpensively. I will make a great wall on our southern border, and I will make Mexico pay for that wall. Mark my words’, Donald Trump said in his speech that launched his presidential campaign in 2015[i]. His victory was undoubtedly a major event not only for US foreign policy but also for the perception of the United States as a whole nation abroad. In particular, Trump’s discourse directed at the neighbouring Latin American country and at the Latin American immigrants who cross the US-Mexican border might have caused a decline in perceiving a US positive image not only amongst Mexicans but amongst citizens in other Latin American countries. A positive image is important for any country. If people from abroad perceive the state positively, they will tend to trade with it, visit it as tourists and above all, they will look up to it, which is extremely important in the case of a superpower that has the ambition to influence world events.

We use data from public opinion polls that provide Latinobarómetro[ii] for 2016 and 2017. We explore the impact of Donald Trump’s election on the perception of the United States among Latin American people. Our research interest is to find out what variables are significant in explaining the opinion of the United States. We compare how Obama’s administration was perceived amongst Americans compared to Trump’s administration. The study does not only attempt to offer descriptive tables, but we use regression models to comprehensively explain the perception of the United States as a nation across Latin America and time.

We assume a worse opinion of the United States in Mexico following Trump’s discourse related to constructing the Wall bordering Mexico, as well as his speeches and actions against Venezuela, Peru and other countries in Latin America such as Colombia that has been an ally of the United States in the war on drugs. We divided the article into four sections. First, we present a theory from the existing research and formulate hypotheses. In the second part, we introduce Trump’s rhetoric addressing Latin America, as shown in his tweets, and the reaction of Latin American presidents. We also offer a descriptive statistic from opinion polls. While it is possible to see the changes in the opinion of the United States in descriptive tables, it is not possible to verify hypotheses while controlling other variables. Therefore, in the third section, we discuss methodology and present dependent, independent and control variables. In the last part, we interpret the results.

This article is a contribution to a literature that examines the opinions and views of nations about other nations[iii],[iv],[v],[vi],[vii],[viii],[ix]. More specifically, this article focuses on the opinion of other nations about the United States[x],[xi],[xii]. This discussion about Trump’s policies and influence in politics is topical[xiii],[xiv],[xv],[xvi] and this paper contributes to it.

Theory and Hypotheses

We apply the concept of anti-Americanism and the theory of international trust to determine how the Latin American public opinion of the United States has changed with the election of Donald Trump as president.

We use the concept of anti-Americanism in the context of a negative opinion of the United States amongst the Latin American masses. Katzenstein and Keohane[xvii] define it as a ‘psychological tendency to hold negative views of the United States and of American society in general’. Anti-Americanism stems mainly from the special position of the United States in world affairs[xviii],[xix]. The hegemonic aspirations of the world power, whether past or present, are a key factor in the negative view of the United States. In recent years, researchers have used multivariate analyses to study anti-Americanism. We also apply this innovative approach in this paper to contribute to this methodological debate on the subject[xx],[xxi],[xxii],[xxiii].

It is not clear that anti-Americanism is the same as the general opinion of the United States. Beyer and Liebe[xxiv] called it a shortcoming in operationalisation when researchers use anti-Americanism and public opinion interchangeably. Beyer and Liebe[xxv] find that the opinion of the United States is more a critique of US foreign policy. The foreign opinions of the United States are more influenced by the US policy than the opinions of Americans. Therefore, the opinion of Americans should be a better measure of anti-Americanism. However, the operationalisation of the opinion of the United States as anti-Americanism is a common practice in research[xxvi],[xxvii],[xxviii]. We proceed with caution and accept that we do not try to explain anti-Americanism among Latin American citizens, but merely their opinion of the United States that is more likely to correspond to US officials and their foreign policy. We include Donald Trump as an independent variable. However, due to the close relation of the anti-Americanism with the opinion of the United States, we use independent variables and control variables that use similar anti-Americanism research to explain an opinion of the United States.

However, anti-Americanism is not the only concept that we use with Latin American public opinion polls. We also include the theory of trust. The opinion is directly related to trust. It is not possible to build lasting bonds and strive for good relations without a positive opinion based on trust. The United States has experienced increased mistrust, for example, in the context of the war in Iraq. Unfound weapons of mass destruction have caused great distrust among the citizens of foreign countries. Some of them have seen ulterior motives in the US foreign policy, and this fact undoubtedly has influenced the very view of the US and has greatly worsened it[xxix]. Even though opinion and trust are not the same, they are very closely related. The theory of trust is a relatively popular theoretical approach among academics dealing with international relations. Researchers have used this theoretical framework in studies on international economic relations, and they have tried to explain how trust between business partners can be reflected in trade[xxx],[xxxi],[xxxii],[xxxiii].

Brewer and his colleagues consider general trust in other nations as a key component of public opinion that shapes views on foreign or world affairs[xxxiv],[xxxv],[xxxvi]. They define trust in other nations and international trust as: ‘generalized belief about whether most foreign countries behave in accordance with normative expectations regarding the conduct of nations’[xxxvii].

We consider the view of the United States as closely related to the opinion of the leadership of this country. It is the presidential system of government, as well as in Latin America, where the president is the head of government and the head of state. His actions and speeches articulate the views and demands of the American public. We assume that Trump's negative discourse was reflected in the opinion of the United States amongst the Latin American public.

H1: A Latin American citizen is more likely to have a worse opinion of the United States during Trump's first year in the office than in the last year of Obama's term.

Political Ideology

Political ideology is very important when explaining the actions of citizens. They often follow suit of the political leaders of their favourite party and accept their opinions[xxxviii]. For example, conservative leaders regularly pursue an isolationist discourse. Therefore, sympathisers of conservatism as an ideological doctrine are more sceptical in trusting other nations. On the contrary are cases of liberal parties and their supporters[xxxix].

In the context of Latin America, it is crucial to distinguish where left-wing and right-wing regimes prevail. The United States, especially through its political and economic system, can be perceived as right-wing, especially by socialist countries such as Cuba and Venezuela. In addition, historically, the United States has either supported right-wing regimes or tried to remove left-wing leaders. In the past, the United States argued that they were exporting democracy and trying to prevent the onset of undemocratic communist regimes. The United States still presents itself as a democracy by which others can be inspired.

Left-wing leaders in countries are also driving the anti-capitalist discourse towards the United States, and this affects the supporters of their left-wing parties. The democracy and business practices of the United States is one of the dimensions of anti-Americanism[xl]. Beyer and Liebe[xli], as part of their research on anti-Americanism in four European countries, include the political spectrum, democracy and market economy as variables to explain anti-Americanism.

H2a: The more left-wing a Latin American citizen, the worse opinion they have of the United States.

H2b: A Latin American citizen believing in democracy is more likely to have a better opinion of the United States.

H2c: A Latin American citizen believing in a free market is more likely to have a better opinion of the United States.

Interpersonal trust

People use their beliefs about other people and human nature to make decisions and create opinions in different situations and about a range of subjects[xlii]. Kaltenthaler and Miller[xliii] find that interpersonal trust is an important factor in shaping a positive attitude and promoting free trade agreements. In general, trust between people and groups contributes to positive attitudes[xliv]. The social trust influences a citizen’s opinion on world affairs[xlv]. Citizens trusting others trust more nations than people that regard their fellow citizens as untrustworthy[xlvi]. From the afore-mentioned theories, we expect that respondents that do not trust their fellow citizens are more likely to distrust the United States. Therefore, they would not have a positive opinion of the United States.

H3: A Latin American citizen trusting his fellow citizens (interpersonal trust) is more likely to have a better opinion of the United States.

Political trust

Similar to social trust, people use political trust as an information shortcut for creating an opinion on a wide range of policy issues[xlvii],[xlviii]. Belief in government helps explain the opinion of citizens about a number of foreign policy issues[xlix],[l]. In addition, Brewer[li] finds that citizens with higher trust in the national government have even greater trust in other nations. We expect that lower trust in national political institutions, which in our case expresses political trust, leads to less trust in other countries and our case, lower trust in the United States, and thus a worse opinion of the United States.

H4: The less trust a Latin American citizen has in national political institutions, the worse the opinion they have of the United States.

Trump’s rhetoric towards Latin America and reactions of Latin American leaders

‘When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. They’re sending us not the right people. It’s coming from more than Mexico. It’s coming from all over South and Latin America. And it’s got to stop, and it’s got to stop fast.’ These are probably the most offensive passages from Donald Trump's Presidential Announcement Speech, referring not only to Mexicans but also to Latin Americans in general[lii].

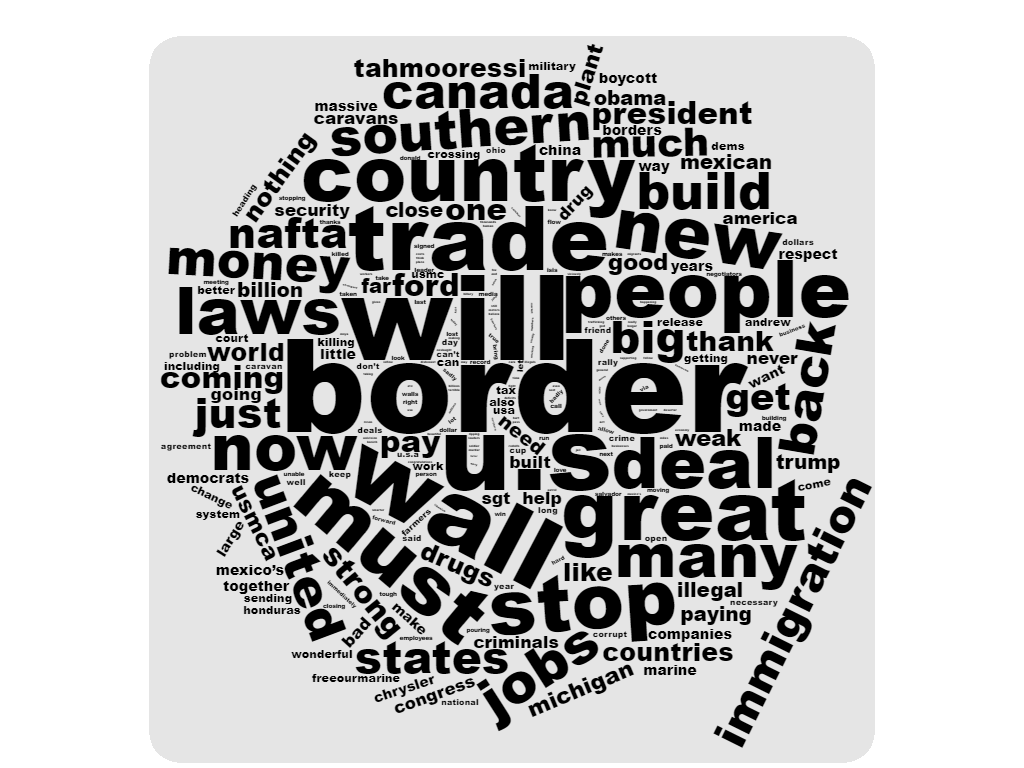

Source: Twitter, a figure created by authors

Figure 1 shows Trump’s tweets that included keyword Mexico from 2014 to March 2019. It is possible to see that keywords such as ‘wall’, ‘stop’, ‘pay’ and ‘illegal’ are key in Trump’s rhetoric. These keywords are not positive and have an impact on Mexican’s opinion of Trump.

We present the results of opinion polls in a comparative perspective. Also, we summarise the reactions of presidents in Latin America to the election of Donald Trump and his subsequent statements and speeches. We focus on the presidents, because presidents are heads of states and the most important office in Latin American countries, and their discourse could influence their citizens.

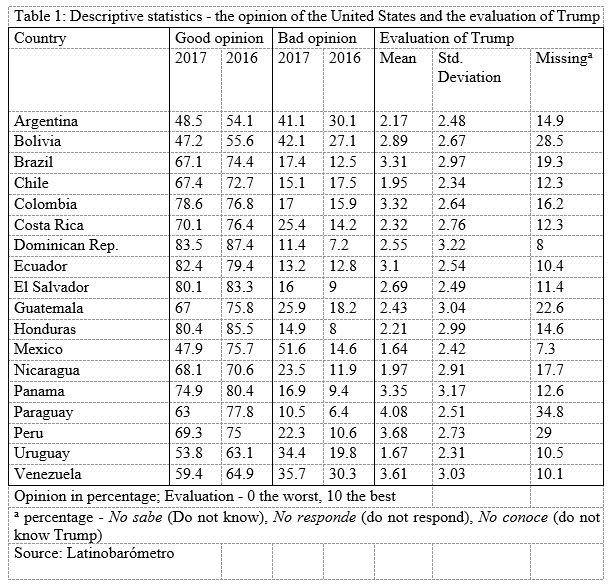

The overwhelming majority of citizens in Latin American countries indicated worse opinions on the United States with the arrival of Trump. However, it was only a few percent for some countries. The biggest deterioration of opinion was expected, and was, from Mexico. Therefore, we dedicate a larger part of this chapter to Mexico than to other countries.

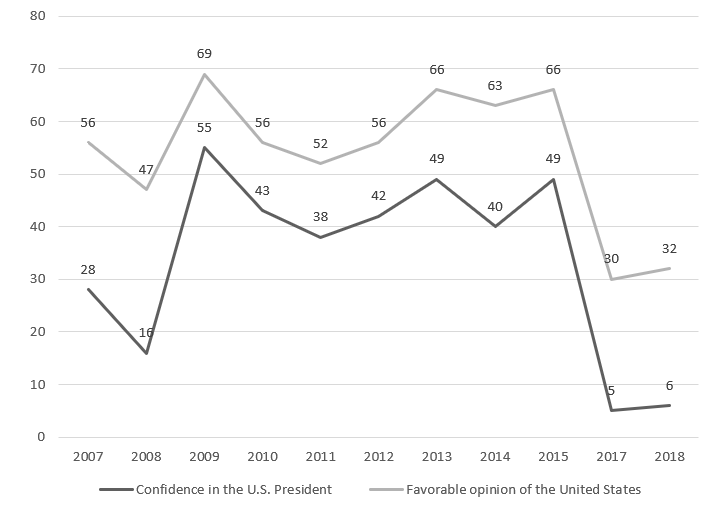

Unfortunately, Latinobarómetro does not offer data about the evaluation of the previous US presidents. Nevertheless, the Pew Research Center offers these data from previous years in the case of Mexico. Figure 2 shows confidence in the US President and the opinion of the United States in Mexico. In the case of George W. Bush at the end of his term, only 16 percent of Mexicans had confidence in him. This is not surprising, because citizens of many other countries had low confidence in Bush’s administration. War in Iraq and unfound weapons of mass destruction had their toll all over the world[liii]. The confidence in the US presidency was not recovered until Obama’s arrival. Barrack Obama convinced Latin Americans with the slogan ‘Yes We Can’. After his election, the confidence in the US President raised from 16 percent under Bush to 55 percent. This figure was his peak, during his presidency around 40 percent Latin Americans had confidence in him, and it rose to 49 percent at the end of his presidency. There was a radical shift with Trump’s administration, and the confidence in it amongst Mexicans fell to only 5 percent. Moreover, only 30 percent of Mexicans had a favourable view of the United States in 2017. Twice the number of Mexicans had a favourable view of the United States under Obama. Figure 2 clearly shows the correlation between the confidence in the US President and opinion of the United States. The Pearson correlation coefficient is 0.949 for these two variables. Therefore, the confidence in the US Presidents is strongly connected to the general view of the United States. In explaining foreign views of the United States, the US President is a key variable.

Figure 2. Mexico – confidence in the US President and the opinion of the United States

Source: Pew Research Center [liv],[lv]

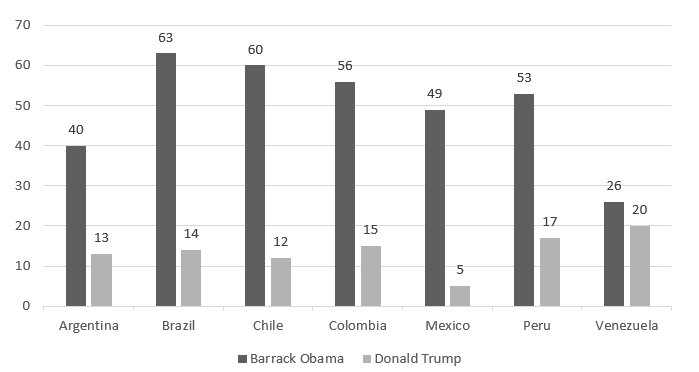

Figure 3. Seven Latin American countries – confidence in the US president

Source: Pew Research Center[lvi]; the survey was not conducted in 2016; data are from the following years: Obama –2015 (Colombia 2014); Trump – 2017

Figure 3 shows that in all countries the confidence in the US President fell under Trump’s administration. Mexicans had the lowest confidence in Trump with only 5 percent. Venezuelans had the greatest confidence in Trump, and it was only 20 percent. Venezuela is also the only country that had low confidence also in Obama. Citizens of other countries had dramatically less confidence in Trump than in Obama. Three times as many people had confidence in Obama than in Trump in Argentina and Peru. In Brazil and Colombia, it was almost four times as many citizens, and in Chile five time as many citizens.

Mexico was most affected by Trump’s speeches. ‘Build the Wall’ was one of the most used slogans in Trump’s presidential campaign. It was part of his policy concerning immigration from Mexico and other Latin American countries. Moreover, he said that the United States would not pay for the wall, but Mexico would pay for it. These speeches provoked a number of emotional reactions. For example, Vicente Fox, who was Mexican president between 2000 and 2006, said in the interview on Fusion in February 2016: ‘I’m not going to pay for that fucking wall. He should pay for it. He’s got the money’ and ‘This nation is going to fail if it goes into the hands of a crazy guy’. Trump visited Mexico a few months later. On August 30th, 2016, he tweeted: ‘I have accepted the invitation of President Enrique Peña Nieto, of Mexico, and look very much forward to meeting him tomorrow”.[lvii] A day later Trump tweeted: ‘Former President Vicente Fox, who is railing against my visit to Mexico today, also invited me when he apologized for using the “f bomb’”. Fox replied to him on Twitter: ‘I invited you to come and apologize to all Mexicans. Stop lying! Mexico is not yours to play with, show some respect’.[lviii] Fox was one of the roughest critics of Trump. This meeting between Trump and Peña Nieto was held several months before he was elected. Trump tweeted on August 31st, 2016 after the meeting: ‘Mexico will pay for the wall - 100%!’[lix]. Peña Nieto reacted to this tweet on his account: ‘I repeat what I told him personally, Mr. Trump: Mexico will never pay for a wall’.[lx] The following month in his address at the United Nations Summit, Peña Nieto said on the subject of Trump's efforts to deport immigrants, which are primarily Mexican: ‘We Mexicans firmly believe that this mestizo fusion is the future and destiny of humankind’.[lxi] The tense relations continued after Trump was elected and became the US President.

Later, after his election, the White House announced Trump wanted to collect a 35 percent border tax from Mexican companies. This would hurt the Mexican economy because Mexico exports over 70 percent of its products to the United States[lxii]. These very statements had an impact on the Mexican economy and were one of the reasons that the Mexican peso was at near an all-time low when Trump became president[lxiii].

Trump issued Executive Order 13767 that mandated construction of the wall after he became president on January 25th, 2017[lxiv]. This action led to hostility between him and Peña Nieto before a scheduled visit that was supposed to happen a few days later. Peña repeatedly rejected Trump's proposal about the wall before the election. On January 26th, 2017, Peña Nieto said in his video address to the nation via Twitter: ‘I regret and condemn the United States’ decision to continue with the construction of a wall that, for years now, far from uniting us, divides us’. Trump tweeted on the same day: ‘If Mexico is unwilling to pay for the badly needed wall, then it would be better to cancel the upcoming meeting’.[lxv] Peña Nieto also stated on Twitter: ‘Mexico doesn't believe in walls. Our country believes in bridges’.[lxvi]

There were hostilities between them before Trump assumed office. However, in his very first week in office, US–Mexican relations changed course. Undoubtedly, these Twitter and other public exchanges between the two presidents were noticed by citizens, and Trump’s foreign policy towards Mexico had an impact on the low confidence in him amongst the Mexicans. Now, we recall reactions of other Latin American presidents towards Trump’s policies.

Brazilian President Michel Temer said that Trump's victory ‘doesn’t change the relationship between the two countries in any way’.[lxvii] However, the image of the United States amongst Brazilians worsened by 5 percent. Trump’s slogans ‘buy American, hire American’ had less impact in Brazil than in Mexico possibly because Brazil does not have the same extensive trade agreement with the United States as Mexico does[lxviii].

After Trump’s election, Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos was full of optimism, and he said: ‘We celebrate the United States’ democratic spirit on Election Night. We’ll continue to deepen the bilateral relation with Donald Trump’.[lxix] Unlike the majority of countries in Latin America, the image of the United States amongst Columbians did not worsen. It is worth remembering that Colombia has long been the largest recipient of US financial aid in the Western Hemisphere, whether in the fight against drugs and drug cartels or in the reconstruction of the country related to fighting guerrilla movements.

Peruvian President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski also congratulated Trump on his election. However, he commented on Trump’s actions after a few months as follows: ‘We are going to grab a saw and cut … He wants to put up a wall between the United States and Latin America and make the Mexicans pay for it. Isn't that too much’?[lxx] Despite these statements, the Peruvian opinion of the United States did not worsen to the same degree as Mexico’s.

Chilean President Michele Bachelet supported Hillary Clinton and addressed Trump before the election: ‘I would want that the president of the US would be someone who is friendly and would respect countries and civilities’.[lxxi] However, the well-known Bachelet's opposition to Donald Trump was not reflected in Chilean opinion. Chilean opinion of the United States remained similar to that under Barack Obama.

Even though Argentinian President Mauricio Macri and his administration sympathised with Clinton, he congratulated Trump after the election. Before the election, he could not imagine him as a president when he stated the following: ‘I believe in relationships, in networks — we are, in fact, speaking with the world through a network — not in building walls’ and that it ‘would be hard to work with someone who would want to build walls’.[lxxii] Similarly, the citizens of Argentina looked at Trump’s election negatively, and bad opinion of the United States increased by 11 percent. Bolivian President Evo Morales congratulated Trump with some irony in his statement: ‘We hope to work against racism, machismo, and anti-immigration for the sovereignty of our people’.[lxxiii] Similarly, the bad image of the United States among Bolivians increased by 15 percent as some probably felt the same way as Morales.

Trump's deportation plans do not concern only Mexico, but also other Central American countries. Currently, there are more than three million immigrants in the United States, mostly from El Salvador, Guatemala but also from Costa Rica. Their deportation could destabilise the already bad security situation in Central America[lxxiv],[lxxv]. Even though a number of Central American countries worsened their opinion of the United States, this is not as significant a change as in Mexico. Nevertheless, Trump's negative discourse on immigrants was addressed to them as well. Latin Americans regularly migrate to the United States for better living conditions or to seek protection from criminal gangs and armed groups operating in their countries. However, countries such as Guatemala and El Salvador are not explicitly mentioned in his speeches, unlike Mexico, which may only be the reason for a slight worsening in the opinion of the respondents. Although many Latin American officials spoke out against Trump or in support of Mexico it did not have a significant effect on the respondents. Concerns about the realisation of Trump's plans were reflected in the Latin American and Caribbean leaders' summit that was hosted by the Dominican Republic just a few days after Trump's election. In his opening speech, President of the Dominican Republic Danilo Medina said ‘We are worried by the growing discourse of protectionism and the closing of borders that is not limited to the economic sphere but which could also seriously affect our migrant populations’ in response to Trump's slogan America First, which can be described as a hard-line approach of governing that represents a review of the trade pacts, deporting migrants and building the wall. Moreover, Ecuadorean President Rafael Correa added: ‘We have to protect ourselves from other things: the persecution of migrants’.[lxxvi] However, it must be mentioned that Trump migrant separation policy and Central American migrant caravans of 2018 are not reflected in 2017 Latinobarómetro. Therefore, it is possible that the opinion worsened more amongst Central American countries.

Trump has criticised two more important Latin American countries. The first was Venezuela, which is an important trading partner because of oil. Trump condemned authoritarian President Nicolas Maduro during the campaign[lxxvii]. However, Venezuelan’s opinion of the United States only marginally worsened maybe due to the fact that Maduro's opponents welcomed such criticism. The second country that was very frequent in Trump's discourse was Cuba. Unfortunately, this country is not included in this paper due to the absence of data. Latinobarómetro did not conduct a public opinion poll in that country. However, given its relevance, we mention Trump's discourse. First, he criticised Obama’s administration. He argued that while he agreed to warm relations with Cuba, he would negotiate a much better deal. Subsequently, he suggested condemning this détente with Havana altogether if Cuban officials would not allow much deeper political and religious freedom in the country. Fidel Castro’s death also confirmed the US hard line towards Cuba: ‘Fidel Castro's legacy is one of the firing squads, theft, unimaginable suffering, poverty and the denial of fundamental human rights’, and ‘but all of the concessions that Barack Obama has granted the Castro regime were done with executive order, which means the next president can reverse them. And that is what I will do unless the Castro regime meets our demands’.[lxxviii]

Although individual country data are not available about Cuba, deterioration of relations was evident within the administration from the Cuban counteraction. Exactly the day after Trump's election, Cuba responded demonstratively and announced a five-day military exercise to face ‘a range of actions by the enemy’[lxxix]. His predecessor, Barack Obama, who achieved the Cuban détente, tried to minimise the damage after Trump's election within his trip in Latin America. He stated: ‘My main message to you ... is don’t just assume the worst’, during his question-and-answer session in Peru. He also said: ‘With respect to Latin America, I don't anticipate major changes in policy from the new administration’.[lxxx]

In general, the people of Latin America evaluate Donald Trump pretty negatively in all countries. The respondents could evaluate Trump on the scale from 0 to 10. He is worst evaluated by Mexicans, which could explain the worsened opinion of the United States as a whole country. The Mexican mean is only 1.61. Trump is best rated by respondents in Paraguay. However, the mean of this country is also only 4.08.

Methodology

Data

We used data from Latinobarómetro that regularly conducts polls in Latin American countries (usually once a year). As part of our research, we used data from 2016 and 2017 that, as we explain in the following section, include key variables that are part of the models.

Dependent variable

The dependent variable is the public opinion[lxxxi] amongst Latin American citizens as regards US foreign policy. The variable itself has four values. The respondent could reply that he had a very positive, positive, negative or very negative opinion of the United States. We decided to dichotomise this variable, and we divided it into a positive and negative opinion. Although dichotomisation is often considered by many to be problematic, criticism is particularly concerned when dichotomising continuous variables[lxxxii],[lxxxiii],[lxxxiv],[lxxxv],[lxxxvi]. This is not the case with this research. Moreover, Latinobarómetro proceeds in its final reports in the same way, and it adds up positive and negative opinions together[lxxxvii],[lxxxviii]. Quiroga[lxxxix] also, in a similar way based on Latinobarómetro data, dichotomises his dependent variable. At the same time, the positive and negative opinions prevailed[xc] over very positive and negative opinions, and for this reason it made sense to merge the variable into two categories. Such a dichotomised variable also had a sufficiently high correlation[xci], demonstrating that this process did not result in a significant loss of information. The pros, especially in the form of a model that will enable logistic regression and simpler interpretation, therefore clearly outweighed the cons.

Independent variables

The first independent variable is the year in which a public opinion poll was conducted. We coded 2017 as 1 and 2016 as 0. Barrack Obama's term came to a close in 2016, while 2017 is Donald Trump's first year in office. In 2017, the survey took place between June and August across Latin America[xcii]. Latin Americans did not only respond to the election result that certainly had some impact, but they judged at least half a year of Donald Trump's presidency. In 2016, surveys were conducted before Trump's victory between May and June[xciii].

The other two independent variables are based on the theory of trust. The first concerns interpersonal trust in fellow citizens and has only two values. We coded the attitude[xciv] that one can trust most people as 1, while if the respondent said caution is required, we coded it as 0. The second variable examines the political trust in the national institutions. There was a total of three questions, classic Likert items, about parliament, national government and political parties. Some researchers criticise the use of individual Likert items[xcv],[xcvi]; some see it as nonproblematic[xcvii], and those in the middle say that once we got the Likert scale, it is no longer problematic[xcviii]. Similarly, we added up[xcix] these three Likert items and got a scale from 3 to 12 that we considered being the ideal expression of political trust in the national institutions (government, parliament and political parties) arising from Latinobarómetro data.

The other three variables relate to ideology and beliefs. Latinobarómetro includes a question on the political spectrum. The respondents assigned themselves on a scale from 0 (the most left-wing) to 10 (the most right-wing), and we included this variable in this format. We dichotomised the other two variables. The first of them is whether democracy[c] is the best system of government and the second question[ci] is about the market economy. Respondents had the opportunity to answer questions strongly agree, agree, disagree and strongly disagree. The reasons for the dichotomisation process are the same[cii] as for the dependent variable. Therefore, we coded a positive relationship to democracy as 1 and a positive relationship to a market economy as 1; we coded negative relationships as 0.

Control variables

We also used five control variables. These variables are based on literature and are a regular part of political science research with opinion polls[ciii],[civ],[cv],[cvi],[cvii],[cviii],[cix],[cx],[cxi].

For a gender variable, we coded women as 1. We did not modify the variable age in any way. Also, we did not modify the education variable that was based on the interviewers' coding. They assigned the respondent's level of education to the 1-7 scale where 1 meant the respondent is illiterate and 7 meant that a respondent completed higher education[cxii]. The other two control variables relate to the respondent's standard of living. The first is the evaluation of the interviewer who evaluated the socio-economic level of the respondent according to the type of housing, equipment and other factors. The scale was 1 for very good, and 5 was very poor. Researchers use similar scales in research with opinion poll data, either LAPOP or Latinobarómetro, and also use regression models[cxiii],[cxiv],[cxv],[cxvi],[cxvii]. Similar scales can be used in regression models (Norman, 2010). The respondents answered the second question[cxviii], and it concerned finance. Here again, we dichotomised the variable. We merged answers: ‘we have enough resources, and we can save’ with ‘we have enough, we have no problems’, which we encode as 1. We merged answers: ‘we do not have enough resources, and we have problems’ with ‘we have not enough resources and we have big problems’ that we coded as 0. The arguments for this process are the same[cxix] as in previous cases. We considered these two variables ideal for inclusion in research for comparative value across Latin America. These variables are important to include because of the advanced level of globalisation and a high level of poverty in a number of Latin American countries. The wealthy population through openness and cooperation with such a large trading partner as the United States have the opportunity to profit. The poorer population have much less adaptability and are more vulnerable to economic changes such as recession or stagnation. On the contrary, the rich are more resilient[cxx],[cxxi]. We included also age. Scepticism grows with increasing age through experience[cxxii]. The presence of the United States was counterproductive in many cases and countries of left-wing leaders, support for right-wing undemocratic regimes (Brazilian junta, the Somoza family in Nicaragua, etc.), promoting neoliberal reforms that have impacted on the low-income population.

Model

The dependent variable is dichotomous. Therefore, we used logistic regression, especially in terms of assignation to the political spectrum, relation to democracy and the market economy, we could assume correlations. Therefore, we proceeded with caution about multicollinearity in modelling. We calculated the variance inflation factor (VIF), and it did not exceed 1.16[cxxiii] in any independent or control variable in Model 1, and no significant multicollinearity was found to prevent interpretation of the results. In Model 1, which includes all Latin-American countries of Latinobarómetro from 2016 and 2017, we controlled the impact of individual countries by including dummy variables, and we used a fixed effects model. We did not use the hierarchical (multi-level) model because we investigated data at the individual level in our research. Moreover, hierarchical models are in some cases methodologically problematic, and some recommend using fixed effect models instead[cxxiv]. This is particularly the case when there are not enough cases for effective analysis at a higher level. For example, Kreft[cxxv], Hox[cxxvi] or Snijders and Bosker [cxxvii] suggest the 30/30 rule of thumb, that there are at least 30 cases per each level. Our research included 18 countries. Therefore, it would not meet these oft-cited conditions. To capture the different situation across Latin America, logistic regression was applied to each country separately, and the values themselves are not presented to save space[cxxviii], but the statistical significance of each variable in Table 3 is presented. Unfortunately, 35.2 percent of cases could not be included in the analysis because they were missing from the data set. In these cases, the respondent refused to answer or did not have an opinion about the asked question.

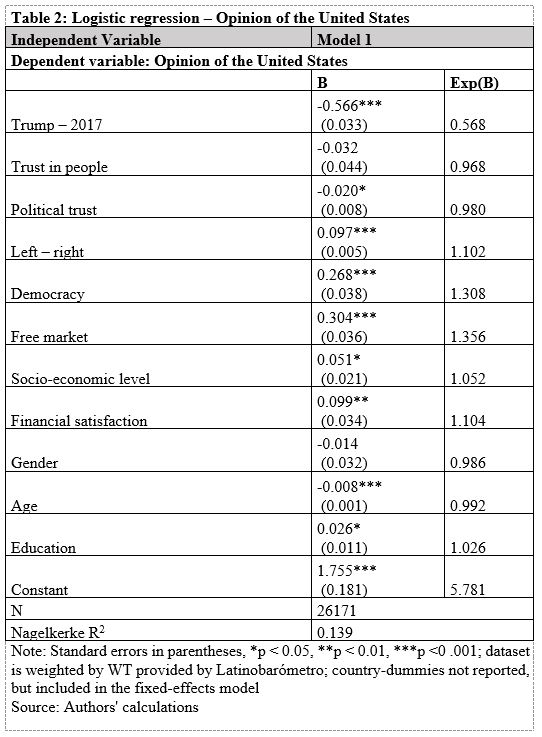

Table 2 shows the results of logistic regression with all countries included. One of the independent variables is the year 2017 when Trump became president. A respondent from 2016 is 43 percent more likely to have a positive opinion of the United States than a respondent from 2017, and this variable is statistically significant. Therefore, we support the first hypothesis. Other hypotheses are not linked to the impact of the change of presidents. They are focused on general factors that may have an impact on public opinion of the United States in Latin America. The first of them, the second hypothesis, consists of three sub-hypotheses. These include political ideology and opinions about the free market and democracy. All these variables are statistically significant and in the expected direction. Therefore, all these sub-hypotheses are supported. A respondent is 10 percent more likely to have a positive opinion of the United States for each one point to the right on the left-right political spectrum. The scale is between 0 and 10 points. The United States has long supported right-wing governments in Latin America. Therefore, it is no surprise that left-leaning citizens have a worse opinion of the United States. A respondent that always considers democracy as a correct form of the government is 30 percent more likely to hold a positive opinion of the United States than a citizen with the opposite view. The United States has presented itself as a leading country of the free world and long-time supporter of democracy. Moreover, a respondent that considers a free market as the only way forward for developing countries is 35 percent more likely to hold a positive opinion of the United States than a citizen with the opposite opinion. The United States is known as a strongly capitalist country, and it has pushed neoliberal right-wing reforms in Latin America.

The third hypothesis examines interpersonal trust. This variable is not statistically significant, and we reject this hypothesis. It seems that low interpersonal trust does not help us to explain the opinion of the United States. However, the fourth hypothesis includes political trust, and this variable is statistically significant and in the expected direction. Therefore, we accept this hypothesis. A respondent is 2 percent more likely to have a positive opinion of the United States for each one-point political trust on the scale of is between 3 and 12 points. It seems that trust in national political institutions (in this case the national government, parliament and parties) can predict the respondent’s opinion of the United States.

Table 2 also shows that all control variables except gender are statistically significant. The better off people are, they more likely they are to have a better opinion of the United States. It is probably because they consider themselves as ‘winners’ in the current system. They possibly welcome globalisation or the influence of the United States in their national economy because it allows them to have a good living standard. Therefore, they are in contrast to ‘losers’ that live in bad economic conditions and have major financial problems. They can partially blame the United States and its influence for their misfortune. Similarly, more educated respondents are more likely to have a better opinion of the United States. Educated people are generally more knowledgeable and have greater access to information, and they can compare living conditions in the United States to their own country. They are more likely to speak the English language and, therefore, experience greater cultural influence and are more likely to start their careers in the United States.

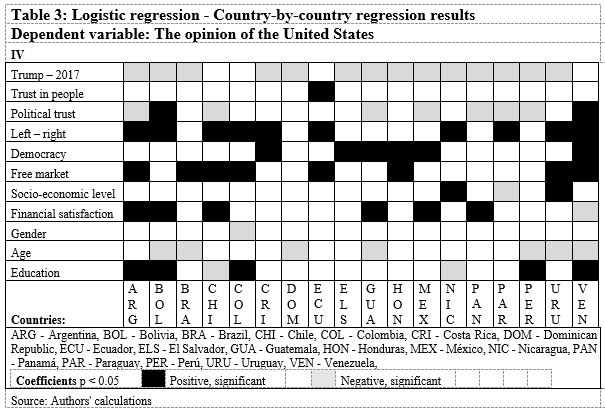

Table 3 shows logistic regression for each country separately. It is possible to see a pattern. The most variables are in the same direction across Latin America when they reach statistical significance. We can see a few interesting exceptions. First, gender is only significant in Colombia. The men are 33 percent more likely to have a positive opinion of the United States than women. In particular, thanks to US financial and military assistance, Colombia succeeded in weakening the largest drug cartels in the 1990s and the largest Colombian guerrilla movements FARC and ELN. Therefore, the United States may appear to be a great help for Colombian men, because arguably a lot of innocent lives, especially Colombian soldiers and police officers, have been saved. Colombian women, however, do not seem to get help from the United States in the same way.

Political trust is a positively significant variable only in Bolivia and Venezuela. This variable is in other countries is in the opposite direction or is not significant. This is probably because in these countries left-wing politics dominates the scene, and that has invigorated the rhetoric of anti-Americanism. Obviously, in this case, the respondent with low trust in national political institutions would favour the United States to their government, parliament and political parties.

Again, Venezuela is the only country where financial satisfaction is a negatively statistically significant variable. It is possible that people who do not have an income to cover their basic needs speak positively of the United States because they blame their socialist government for the economic failures. The left-wing government has used anti-American rhetoric. Therefore, they positively perceive the United States as a country that defies Maduro's regime and urges it to provide the basic needs of the Venezuelan people.

Conclusion

During President Trump’s first year in office, the people of Latin America had a worse opinion of the United States than during Obama’s term. However, this unfavourable image is not the same in all countries. Unsurprisingly, Mexico was a country where public opinion of the US was the worst in Latin America. However, some countries did not experience a significant drop in the opinion of the United States. This was the case of Central American countries as well as Colombia, which has been long a recipient of significant aid from the United States. However, Latin American people evaluate Donald Trump negatively, irrespective of their national countries. He was best rated on the scale from 0 to 10 in Paraguay with the mean of 4.08, which is quite low.

Having included 18 Latin American countries in our fixed-effects model we found that respondents with a positive view about democracy and the free market hold a more likely positive opinion of the United States. Moreover, the more right-wing the person, the more likely the positive opinion of the United States. Another independent variable, political trust in national political institutions, is significant in a prediction about an opinion of the United States. The less trust a Latin American citizen has in national political institutions, the worse the opinion they have of the United States. However, this is not the case for Venezuela and Bolivia. Interpersonal trust is not statistically significant in our model as much as our control variables. The financially satisfied citizens have a better opinion of the United States than citizens that are not happy with their income. Also, more educated people have a better opinion of the United States. The gender is not a statistically significant variable except in the case of Colombia.

Michal Haman is affiliated with the Philosophical Faculty, University of Hradec Králové, and may be reached at michael.haman@uhk.cz.

Milan Školník is affiliated with the Philosophical Faculty, University of Hradec Králové, and may be reached at milan.skolnik@uhk.cz.

This research was supported by a grant from the Philosophical Faculty, University of Hradec Králové.

[i] Time (2015), ‘Here’s Donald Trump’s Presidential Announcement Speech,’ <http://time.com/3923128/donald-trump-announcement-speech/> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[ii] Latinobarómetro (2017a), ‘Banco de Datos - Latinobarómetro 2017 and Latinobarómetro 2016,’ <http://www.latinobarometro.org> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[iii] Laura Considine (2015), ‘Back to the rough ground!’ a grammatical approach to trust and international relations,’ Millennium: Journal of International Studies 44(1), pp. 109-127.

[iv] Christoph Elhardt (2015), ‘The causal nexus between trust, institutions and cooperation in international relations,’ Journal of Trust Research 5(1), pp. 55-77.

[v] Jonathan Fletcher and Andrew Marshall (2008), ‘Is international trust performance predictable over time? A note,’ Accounting and Finance 48(1), pp. 123-132.

[vi] Steven Globerman and Bo B. Nielsen (2006), ‘Trust and the governance of international strategic alliances,’ Corporate Ownership and Control 3(4B), pp. 202-218.

[vii] Iasonas Lamprianou and Giorgos Charalambous (2018), ‘Cue theory and international trust in Europe: The EU as a proxy for trust in the UN,’ Refugee Survey Quarterly 37(3), pp. 463-488.

[viii] Rebecca Lee (2018), ‘The Evolution of the Modern International Trust: Developments and Challenges,’ Iowa L. Rev. 103(5), pp. 2069-2095.

[ix] Simone Polillo (2012), ‘Globalization: Civilizing or destructive? An empirical test of the international determinants of generalized trust,’ International Journal of Comparative Sociology 53(1), pp. 45-65.

[x] Andy Baker and David Cupery (2013), ‘Anti-Americanism in Latin America: Economic Exchange, Foreign Policy Legacies, and Mass Attitudes toward the Colossus of the North,’ Latin American Research Review 48(2), pp. 106-130.

[xi] Sergio Fabbrini (2004), ‘Layers of anti-Americanism: Americanization, American unilateralism and anti-Americanism in a European perspective,’ European Journal of American Culture 23(2), pp. 79-94.

[xii] Max Paul Friedman (2008), ‘Anti-Americanism and US foreign relations,’ Diplomatic History 32(4), pp. 497-514.

[xiii] Lara Minkus, Emanuel Deutschmann, and Jan Delhey (2018), ‘A Trump Effect on the EU’s Popularity? The U.S. Presidential Election as a Natural Experiment,’ Perspectives on Politics 17(2), 399-416.

[xiv] Thomas Rudolph (2019), ‘Populist anger, Donald Trump, and the 2016 election,’ Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties.

[xv] John Street (2019), ‘What is Donald Trump? Forms of ‘Celebrity’ in Celebrity Politics,’ Political Studies Review 17(1), pp. 3-13.

[xvi] Joshua D. Wright and Victoria M. Esses (2019), ‘It’s security, stupid! Voters’ perceptions of immigrants as a security risk predicted support for Donald Trump in the 2016 US presidential election,’ Journal of Applied Social Psychology 49(1), pp. 36-49.

[xvii] Peter J. Katzenstein and Robert O. Keohane (2007), ‘Varieties of anti-Americanism: A framework for analysis,’ in Peter J. Katzenstein and Robert O. Keohane (eds.) Anti-Americanisms in world politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press,p. 12.

[xviii] Andrei S. Markovits (2009), Uncouth nation: why Europe dislikes America, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[xix] Mary Nolan (2005), ‘Anti-Americanism and Americanization in Germany,’ Politics & Society 33(1), pp. 88-122.

[xx] Heiko Beyer and Ulf Liebe (2014), ‘Anti-americanism in europe: Theoretical mechanisms and empirical evidence,’ European Sociological Review 30(1), pp. 90-106.

[xxi] Giacomo Chiozza (2009), Anti-Americanism and the American world order, Baltimore: JHU Press.

[xxii] Matthew A. Gentzkow and Jesse M. Shapiro (2004), ‘Media, education and anti-Americanism in the Muslim world,’ Journal of Economic perspectives 18(3), pp. 117-133.

[xxiii] Leonard Ray and Gregory Johnston (2007), ‘European anti-Americanism and choices for a European defense policy,’ PS: Political Science & Politics 40(1), pp. 85-91.

[xxiv] Beyer and Liebe (2014) p. 95.

[xxv] Beyer and Liebe (2014).

[xxvi] Chiozza (2009).

[xxvii] Pew Research Center (2003), ‘America’s Image Further Erodes, Europeans Want Weaker Ties: But Post-War Iraq Will Be Better Off, Most Say,’ <https://www.pewglobal.org/2003/03/18/americas-image-further-erodes-europeans-want-weaker-ties/> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[xxviii] Pew Research Center (2009), ‘Confidence in Obama Lifts U.S. Image Around the World,’ <https://www.pewglobal.org/2009/07/23/confidence-in-obama-lifts-us-image-around-the-world/> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[xxix] Chiozza (2009), pp. 174–175.

[xxx] María-Pilar Camblor and Carlos-María Alcover (2013), ‘The everyday concept of trust in international cooperation environments,’ Revista de Psicología Social 27(2), pp. 233-241.

[xxxi] Yen-Hung Steven Liu et al. (2018), ‘Always trust in old friends? Effects of reciprocity in bilateral asset specificity on trust in international B2B partnerships,’ Journal of Business Research 90, pp. 171-185.

[xxxii] Devesh Roy, Abdul Munasib, and Xing Chen (2014), ‘Social trust and international trade: the interplay between social trust and formal finance,’ Review of World Economics 150(4), pp. 693-714.

[xxxiii] Eva Spring and Volker Grossmann (2016), ‘Does bilateral trust across countries really affect international trade and factor mobility?,’ Empirical Economics 50(1), pp. 103-136.

[xxxiv] Paul R. Brewer, Scan Aday, and Kimberly Gross (2005), ‘Do Americans trust other nations? A panel study,’ Social Science Quarterly 86(1), pp. 36-51.

[xxxv] Paul R. Brewer (2004), ‘Public Trust in (Or Cynicism about) Other Nations across Time,’ Political Behavior 26(4), pp. 317-341.

[xxxvi] Paul R. Brewer et al. (2004), “International Trust and Public Opinion About World Affairs.,” American Journal of Political Science 48(1): pp. 93–109.

[xxxvii] Brewer et al. (2004), p. 96

[xxxviii] John R. Zaller (1992), The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion, New York: Cambridge University Press

[xxxix] Paul R. Brewer, Kimberly Gross, and Timothy Vercellotti (2018), ‘Trust in International Actors,’ in Eric M. Uslaner (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Social and Political Trust, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 657-686.

[xl] Chiozza (2009).

[xli] Beyer and Liebe (2014).

[xlii] Eric M. Uslaner (2002), The moral foundations of trust, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[xliii] Karl Kaltenthaler and William J. Miller (2013), ‘Social psychology and public support for trade liberalization,’ International Studies Quarterly 57(4), pp. 784-790.

[xliv] Brewer (2004).

[xlv] Paul R. Brewer, and Marco R. Steenbergen (2002), ‘All against all: How beliefs about human nature shape foreign policy opinions,’ Political Psychology 23(1), pp. 39-58.

[xlvi] Brewer, Gross, and Vercellotti (2018).

[xlvii] Marc J. Hetherington (1998), ‘The Political Relevance of Political Trust,’ American Political Science Review 92(04), pp. 791-808.

[xlviii] Marc J. Hetherington and Suzanne Globetti (2002), ‘Political Trust and Racial Policy Preferences,’ American Journal of Political Science 46(2), pp. 253-275.

[xlix] Brewer (2004).

[l] Brewer et al. (2004).

[li] Brewer (2004).

[lii] Time (2015).

[liii] Pew Research Center (2004), ‘A Year After Iraq War,’ <https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/pdf/206.pdf> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[liv] Pew Research Center. (2019), ‘Mexico: Opinion of the United States,’ <https:///www.pewglobal.org/database/indicator/1/country/141/> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lv] Pew Research Center. (2019), ‘Mexico: Confidence in the U.S. President,’ <https://www.pewglobal.org/database/indicator/6/country/141/> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lvi] Pew Research Center. (2019), ‘Latin America: Confidence in the U.S. President,’ <https://www.pewglobal.org/database/indicator/6/group/2/> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lvii] Alex Johnson (2016), ‘Donald Trump to Meet With Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto,’ NBC News, 30 August, available at: <https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2016-election/donald-trump-meet-mexican-president-enrique-pe-nieto-n640441> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lviii] David Wright (2016), ‘Former Mexican President apologizes for Trump invitation,’ CNN, 31 August <https://edition.cnn.com/2016/08/31/politics/vicente-fox-criticizes-trump-nieto-meeting/index.html>.

[lix] BBC (2016), ‘Donald Trump: Mexico will pay for wall, 100%,’ 1 September <https://www.bbc.com/news/election-us-2016-37241284> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lx] Daniella Silva (2016), ‘Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto to Trump: We ‘Will Never Pay for a Wall,’ NBC News, September <https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2016-election/mexican-president-enrique-pe-nieto-trump-we-will-never-pay-n641736> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxi] Hugh Bronstein (2016), ‘Mexican President Peña Nieto: No Barriers Can Stop Immigration,’ NBC News, 19 September <https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/mexican-president-pe-nieto-no-barriers-can-stop-immigration-n650961> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxii] Patrick Gillespie (2017), ‘Trump doubles down on Mexico ‘border tax’ threat,’ CNN, 11 January <https://money.cnn.com/2017/01/11/news/economy/trump-border-tax-mexico/index.html> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxiii] Patrick Gillespie (2017), ‘Mexico’s ‘contingency plan’ for Trump isn’t working,’ CNN, 5 January <https://money.cnn.com/2017/01/05/news/economy/mexico-peso-trump-contigency-plan/index.html> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxiv] White House. (2017), ‘Executive Order: Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvements,’ <https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-border-security-immigration-enforcement-improvements/> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxv] Azam Ahmed (2017) , ‘Mexico’s President Cancels Meeting With Trump Over Wall, New York Times, 26 January https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/26/world/mexicos-president-cancels-meeting-with-trump-over-wall.html (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxvi] Daniella Diaz (2017), ‘Mexican president cancels meeting with Trump,’ CNN, 27 January <https://edition.cnn.com/2017/01/25/politics/mexico-president-donald-trump-enrique-pena-nieto-border-wall/index.html> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxvii] Luciana Amaral (2016), ‘Eleição de Trump não muda nada na relação Brasil-EUA, diz Temer,’ Globo, 9 November <http://g1.globo.com/politica/noticia/2016/11/eleicao-de-trump-nao-muda-nada-na-relacao-brasil-eua-diz-temer.html> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxviii] Shasta Darlington, Flora Charner, and Catherine E. Shoichet (2016), ‘Brazilian Vice President Michel Temer: I want to regain the people’s trust,’ CNN, 26 April <https://edition.cnn.com/2016/04/25/americas/brazil-vice-president-michel-temer-interview/> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxix] Elizabeth Gonzalez et al. (2016), ‘Latin America Reacts to Trump’s Win,’ <https://www.as-coa.org/articles/latin-america-reacts-trumps-win#mex> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxx] Associated Press (2016), ‘Peru’s Kuczynski jokes about ending us ties if Trump wins,’ 21 June <https://elections.ap.org/lakeway/content/perus-kuczynski-jokes-about-ending-us-ties-if-trump-wins> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxxi] Hayes Brown and Karla Zabludovsky (2016), ‘Chile’s President Is Pretty Much Team Hillary,’ BuzzFeed News, 22 September <https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/hayesbrown/chile-we-need-more-female-presidents-in-the-world#.inJbzMvaB> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxxii] Dani Polo (2016), ‘Argentina Reacts to Shock Trump Triumph,’ Argentinai Independent, 9 November <http://www.argentinaindependent.com/news/argentina-reacts-to-shock-trump-triumph/> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxxiii] Gonzalez et al. (2016).

[lxxiv] Shasta Darlington (2017), ‘The other migrant crisis: Thousands risk journey through Latin America,’ CNN, 13 March <https://edition.cnn.com/2016/12/19/americas/costa-rica-migration/index.html> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxxv] Orlando Estrada (2016), ‘Guatemala asks Trump to guarantee ‘protection’ of migrants,’ Businessi Insider, 9 November <https://www.businessinsider.com/afp-guatemala-asks-trump-to-guarantee-protection-of-migrants-2016-11> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxxvi] Ezequiel Abiu Lopez (2017), ‘Leaders from Latin America, Caribbean talk Trump at summit,’ AP News, 24 January <https://www.apnews.com/5f3b362ac65747839db07c5a1efaeebc> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxxvii] CNN (2017), ‘Trump’s wall isn’t Latin America’s only problem,’ 27 January <https://edition.cnn.com/2017/01/26/americas/trump-latin-america/index.html> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxxviii] Jeremy Diamond (2016), ‘Trump shifts on Cuba, says he would reverse Obama’s deal,’ CNN, 17 September <https://edition.cnn.com/2016/09/16/politics/donald-trump-cuba/> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxxix] Elizabeth McLaughlin (2016), ‘Cuba Announces 5 Days of Nationwide Military Exercises,’ ABC News, 9 November <https://abcnews.go.com/International/cuba-announces-days-nationwide-military-exercises/story?id=43418956> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxxx] Jeff Mason (2016), ‘Obama tells Latin America and world: give Trump time, don’t assume worst,’ Reuters, 20 November <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-obama-trump-idUSKBN13F07Y> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxxxi] The exact question is as follows: Do you have a very good, good, bad or very bad opinion about the United States?

[lxxxii] Jacob Cohen (1983), ‘The Cost of Dichotomization,’ Applied Psychological Measurement 7(3), pp. 249-253.

[lxxxiii] Gavan J. Fitzsimons (2009), ‘Death To Dichotomizing,’ Journal of Consumer Research 35(1), pp. 1-4.

[lxxxiv] Robert C. MacCallum, Shaobo Zhang, Kristopher J. Preacher, and Derek D. Rucker (2002), ‘On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables,’ Psychological Methods 7(1), pp. 19-40.

[lxxxv] Steven V. Owen and Robin D. Froman (2005), ‘Why carve up your continuous data?,’ Research in Nursing & Health 28(6), pp. 496-503.

[lxxxvi] David L. Streiner (2002), ‘Breaking up is hard to do: The heartbreak of dichotomizing continuous data,’ Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 47(3), pp. 262-266.

[lxxxvii] Latinobarómetro. (2016), ‘Informe 2016,’ <http://www.latinobarometro.org/LATDocs/F00005843-Informe_LB_2016.pdf> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxxxviii]Latinobarómetro (2017), ‘Informe 2017,’ <http://www.latinobarometro.org/LATDocs/F00006433-InfLatinobarometro2017.pdf> (accessed 15 November 2020).

[lxxxix] Mauricio Morales Quiroga (2009), ‘Corrupción y democracia,’ Gestión y Política Pública 18(2), pp. 205-252.

[xc] For 2016 and 2017 a total of 18.8% of respondents had a very positive opinion of the US, 53.1% positive, 16.9% negative and 4.9% very negative, the rest of the respondents did not respond.

[xci] The Pearson correlation coefficient 0.822 and the Spearman correlation coefficient 0.809.

[xcii] Latinobarómetro (2017b).

[xciii] Latinobarómetro (2016).

[xciv] The exact question is as follows: Generally speaking, would you say that you can trust most people, or that you can never be too careful in dealing with others?

[xcv] In this sense, the dependent variable is also a Likert item, but it did not make sense to add it up with other items because they were different countries. The dependent variable is not a "world" opinion of foreign countries.

[xcvi] Susan Jamieson (2004), ‘Likert scales: how to (ab)use them,’ Medical Education 38(12), pp. 1217-1218.

[xcvii] Geoff Norman (2010), ‘Likert scales, levels of measurement and the ‘“laws”’of statistics,’ Advances in Health Sciences Education 15(5), pp. 625-632.

[xcviii] James Carifio and Rocco Perla (2008), ‘Resolving the 50-year debate around using and misusing Likert scales,’ Medical Education 42(12), pp. 1150-1152.

[xcix] The exact question is as follows: How much trust you have in each of the following groups/institutions. Would you say you have a lot (4), some (3), a little (2) or no trust in (1). In the original questionnaire, a lot was 1 and no trust was 4. Thus, we reversed the values for ease of interpretation.

[c] The exact question is as follows: Democracy may have problems, but it is the best system of government

[ci] The exact question is as follows: Market economy is the only system with which the country can become a developed country

[cii] Regarding the question of democracy, the Pearson correlation coefficient between the newly created variable and the original variable was 0.818, the Spearman correlation coefficient was 0.817. Concerning the market economy question, the Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.842 and the Spearman correlation coefficient was 0.870.

[ciii] Brian J. L. Berry and Osvaldo S. Tello Rodriguez (2010), ‘Dissatisfaction with Democracy: Evidence from the Latinobarómetro 2005,’ Journal of Politics in Latin America 2(3), pp. 129-142.

[civ] Brewer, Aday, and Gross (2005).

[cv] Brewer, Gross, and Vercellotti (2018).

[cvi] Brewer (2004).

[cvii] Brewer et al. (2004).

[cviii] Miguel Carreras and Yasemin İrepoğlu (2013), ‘Trust in elections, vote buying, and turnout in Latin America,’ Electoral Studies 32(4), pp. 609-619.

[cix] Mollie J. Cohen (2018), ‘Protesting via the Null Ballot: An Assessment of the Decision to Cast an Invalid Vote in Latin America,’ Political Behavior 40(2), pp. 395-414.

[cx] Fabiana Machado, Carlos Scartascini, and Mariano Tommasi (2011), ‘Political institutions and street protests in Latin America,’ Journal of Conflict Resolution 55(3), pp. 340-365.

[cxi] Mauricio Morales Quiroga (2009), ‘Corrupción y democracia,’ Gestión y Política Pública 18(2), pp. 205-252.

[cxii] The values - 1: Illiterate, 2: Incomplete primary, 3: Complete primary, 4: Incomplete Secondary, technical, 5: Complete Secondary, technical, 6: Incomplete higher, 7: Complete higher.

[cxiii] Berry and Rodriguez (2010).

[cxiv] Carreras and İrepoğlu (2013).

[cxv] Cohen (2018).

[cxvi] Machado, Scartascini, and Tommasi (2011).

[cxvii] Quiroga (2009).

[cxviii] The exact question is as follows: Do the salary you receive, and your total family income allow you to cover your needs in a satisfactory manner? 1) It is enough, we can save 2) It is just enough, we do not have major problems 3) It is not enough, we have problems 4) It is not enough, we have major problems

[cxix] The Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.867, and the Spearman correlation coefficient was 0.919.

[cxx] Roberto Patricio Korzeniewicz and William C. Smith (2000), ‘Poverty, inequality, and growth in Latin America: Searching for the high road to globalization,’ Latin American research review 35(3), pp. 7-54.

[cxxi] Machiko Nissanke and Erik Thorbecke (2010), ‘Globalization, poverty, and inequality in Latin America: Findings from case studies,’ World Development 38(6), pp. 797-802.

[cxxii] Uslaner (2002).

[cxxiii]Within the fixed-effects model, there were dummy variables for countries, and none of them had VIF greater than 2.27.

[cxxiv] Francis L. Huang (2016), ‘Alternatives to Multilevel Modeling for the Analysis of Clustered Data,’ Journal of Experimental Education 84(1), pp. 175-196.

[cxxv] Ita G. G. Kreft (1996), ‘Are multilevel techniques necessary? An overview, including simulation studies,’ Los Angeles: California State University

[cxxvi] Joop J. Hox (2010), Multilevel analysis: techniques and applications, New York: Routledge, p. 235.

[cxxvii] Tom A. B. Snijders and Roel J. Bosker (1999), Multilevel analysis : an introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling,. London: Sage, p. 154.

[cxxviii]Upon request, we are ready to provide you with a detailed document.