Abstract

The Baltic states, positioned as a conduit between Eastern and Western Europe, possess considerable geopolitical importance for numerous nations globally, including India. India views the Baltic states as a strategic entry point to Western and Northern Europe, offering significant opportunities to strengthen India's ties with the Eastern and Northern European regions. The looming China threat for India and the Baltic states and the growing concentration of power in the Indo-Pacific region have also heightened India’s significance for the Baltic states. In the aforementioned framework, the significance of the relations between India and the Baltic states is underscored by cultural affinity and exchange, geopolitical importance and mutual respect. The connections between India and the Baltic states are driven by three fundamental elements: the political, social and economic. This study will analyse the three key components and the changing dynamics between India and the Baltic states since the resurgence of the Baltic states. This study also explores further avenues for collaboration to enhance India's involvement with the Baltic states, as well as how the imminent risk of China is compelling India and the Baltic states to forge a closer partnership.

Keywords

Introduction

The year 1991 was an important year for India and the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) as the Baltic states were freeing themselves from the clutches of its imperial neighbour and India was changing its economic system from state-driven to market-driven. The Baltic states were in the process of establishing themselves on the world map and India was consolidating its position from an underdeveloped state to a vital state in the world order.

After regaining their independence, the Baltic states rejoined the international community and built a policy to move toward Europe to save their nation from the potential threat of expansionist Russia. Therefore, immediately after the independence, they signed various multilateral agreements with European nations and also became part of various multilateral groups and institutions. In 2004, they became part of the European Union (EU) and North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) to secure both their economic and security interest. India views the Baltic states as a strategic entry point to Western and Northern Europe, offering significant opportunities to strengthen India's ties with the Eastern and Northern European regions (Chadha 2020). The looming China threat for India and the Baltic states and the growing concentration of power in the Indo-Pacific region have also heightened India’s significance for the Baltic states (Grare & Reuter 2021).

The relations between India and the Baltic states are underscored by cultural affinity and exchange, geopolitical importance and mutual respect. The connections between India and the Baltic states have been driven by three fundamental elements: the political, social and economic. This study analyses these three key components and the changing dynamics between India and the Baltic states since the resurgence of the Baltic states. Now the question arises as to why these three components are important in bilateral relations between India and the Baltic states.

Political, cultural and economic components are the basic foundation of bilateral relations between nations or regions because they build a structure of cooperation, coordination and common values. It also shapes the dialogue between nations and influences, everything from diplomatic negotiations to trade agreements. Diplomatic tactics, political systems, ideology and governance styles are some of the major tools of the political component. Political components in bilateral relations are important because political stability and strategic interest help in the formation of stronger ties, while political differences can lead to rivalry or even conflicts (Waltz 1979). Political cooperation also enhances the international transaction which leads to economic stability and growth (Keohane 1984). The economic component in bilateral relations is tangled with political, social and security dynamics. It creates a thread of interdependence that minimises the chances of conflict because the economically intertwined states have a vested interest in maintaining peaceful relations (Keohane & Nye 1977). Political relations not only focus on hard power but also on soft power that influences others through persuasion rather than coercion. Historical ties, common values, language and religion are a vital pillar of cultural components which helps to reduce differences and promote soft power. Cultural exchange and people-to-people contact enhance soft power which leads to cordial and stronger bilateral relations (Nye 2004). Cultural exchange solidifies mutual understanding, shapes national identity and international acceptability, and helps promote international norms and principles (Wendt 1999; Finnemore & Sikkink 1998).

In the above-given context, the study explores the evolution of the relations between India and the Baltic states over the years. However, in the last few years, the geopolitics of the world has changed rapidly with the trade war between the US and China, Russia’s aggression in Ukraine and the rising border dispute between India and China. Relations between India and the Baltic states have also been touched by the changing geopolitical dynamics. This study explores the key areas where India and the Baltic states' interests are aligned especially connecting the Baltic Sea Region (BSR) with the Indian Ocean in the changing geopolitical scenario. This study also explores further avenues for collaboration to enhance India's involvement with the Baltic states, as well as how the imminent risk of China compels India and the Baltic states to forge a closer partnership.

The method used in this paper is descriptive and analytical. Due to limited scholarly articles and books, the arguments in this article largely rely on statements of government officials and the data they provide. The data collected for this paper is mainly from the official government websites of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and India, and their respective embassies. Personal interviews were also used from 2018 field visits to Kaunas Technology University (KTU) in Lithuania and to the Baltic Center at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India.

Evolution of India and the Baltic states’ relations since the end of the Cold War

In 1991, India recognised the independence of all three Baltic states: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, and established diplomatic relations with all three nations in 1992. Since the establishment of diplomatic relations, India and the Baltic states have maintained cordial and respectful relations which are historically driven by three fundamental components – the political, cultural and economic – which still play an important role in fostering the bilateral relations between India and the Baltic states (Sharma 2023).

Since the establishment of diplomatic relations between India and the Baltic states, the cooperation between the states has remained below their expectations. For a long time, neither side in their foreign policy documents prioritised enhancing the cooperation between nations, despite having so many opportunities. However, in the last decade, the Baltic states and India have wanted to enhance their cooperation prompted by shared economic interests, cultural exchange and changing geopolitics and strategic interests. The rise of China and its close partnership with Russia in the Eurasian landmass raised security concerns for the Baltic states that compelled Baltic states to work with rising Asian powers, especially with India. India is similarly facing regional security challenges from China, particularly in the Indian Ocean and Indo-Pacific region; therefore, India is also enhancing its European policy by reaching out to the smaller states of North, South, Central and Eastern European nations.

Historical connections and cultural exchange between India and the Baltic states

The Baltic states are newly independent countries and are still in the process of rediscovering and reinventing their civilisation and cultural past to reconstruct their identity to establish themselves on the map of Europe and their important status in the international system. To establish a close cultural link with India, the Baltic states have made sincere attempts to showcase their interest in Indian thought, culture and ideas. The Baltic states showed their interest in Indian ideas during the last phase of the Soviet Union when the Baltic states were leading a freedom movement known as ‘The Singing Revolution’ and ‘The Baltic Way’, very much inspired by Gandhi’s ideas of Non-violence (Ahinsa) and Satyagraha. Gandhi used these methods to channel the mass movement to free India from the clutches of British colonial rule. Through mass meetings and writing, Gandhi spread the idea of non-violence and Satyagraha as tools of civil resistance to bear the brutal treatment from the British. Baltic freedom fighters also applied the same method against the brutal treatment of the Soviet regime during their freedom movement (Govardhan 2015).

Historical links between the Balts and Indians have not been explored as of now; however, limited available literature and resources suggest that the Baltic states have a solid curiosity towards India and Indology studies. The linguistic similarity between India and Lithuania is conceived as a common thread that links the two states culturally and linguistically. ‘Philologists and historians point out the direct connection of the Latvian and Lithuanian languages to ancient Sanskrit, one of the classical languages in India. The Anglo-German ethnologist Max Muller (1833–1900) also identified a link between the Sanskrit “Deva” (deity: bright or shining one) and the Lithuania “Dievas” or the Latvian “Dievs” (both signifying God)’ (Usha 2015: 97).

The Indo-European background of the Balts and the Aryans was first studied by Indian author Suniti Kumar Chatterji in 1967 who said:

Baltic writers and poets like Andrejs Pumpurs, the Latvian poet who composed the Latvian national epic of Lačplēsis (based on old Latvian ballads and myths and legends) in 1888, and Jānis Rainis (1865‐1929), the national poet of Latvia, and writers also from Lithuania, described in glowing terms how the culture and wisdom and even the origin of the Balts was from far‐away Asia in the East, from India itself. The Latvian writer, Fr. Malbergis, actually wrote in 1856 that the Latvians like the Russians and Germans came from the banks of the Ganga. Another Latvian writer in 1859 put forward the same view. (Chatterji 1967: 17)

Chatterji goes further and says:

During the nineteenth century, when the Baltic peoples, the Latvians and the Lithuanians, began to study their national literature of the Dainas and became conscious of their Indo‐European heritage, through their study of it from the German Sanskritists who took a leading part in establishing the ‘Aryan’ or Indo‐Germanic or Indo‐European bases of the culture of the European peoples, they developed an uncritical and a rather emotional idea that the Baltic peoples came from the East-from Asia-and as they thought, from India too. (ibid)

There is a cultural similarity also found in the historical evidence. Marija Gimbutas (1963: 43) believes that ‘over 4,000 years ago the forefathers of the Balts and the Old Indian people lived in the Eurasian steppes’. A custom similar to India called ‘sati’ was also prevalent in Lithuania. According to Gimbutas,

The frequent double graves of a man and a woman indicate the custom of self-immolation by the widow. The wife must follow the death of her deceased husband- a custom which continued among Hindus in India (Suttee) into the present century, and in Lithuania is recorded in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries A.D. (Gimbutas 1963: 42)

As one of the oldest surviving Indo-European languages, the Lithuanian language exhibits numerous resemblances to Sanskrit, suggesting potential historic connections. Prior to their conversion to Christianity in the 13th century, the inhabitants of Lithuania practiced nature worship. The society worshipped a triad of deities – Perkunas, Patrimpas and Pikuolis. This notion of trinity shares many similarities with Hinduism. Lithuania had its first direct experience of India through the efforts of Lithuanian Christian missionaries who began their service in India around the 16th century. Vydunas, a prominent Lithuanian philosopher and ideologue of the 19th century, showed a profound fascination in Indian philosophy. In fact, he went so far as to develop his own philosophical system, drawing heavily from the principles of Vedanta. During the 1930s and 1940s, Antanas Poska and Matas Salcius, both Lithuanian travellers, dedicated several years to the study of Sanskrit and Indian culture while also embarking on journeys to explore these subjects.

India has had a long-standing relationship with Estonia for many centuries. E. Eckhold is believed to be the earliest known individual of Estonian descent to have travelled to India, arriving there in the late 17th century. In 1797, the Estonian seafarer A. J. Von Krusen Stern travelled to Madras and Calcutta. The ‘Pühhapäiwa Wahhe-luggemissed’ (‘Sunday Intermediary Readings’) by Otto W. Masing, published in 1818, was the earliest Estonian written work to mention India.

In the 19th century, Estonia sent its first missionaries to India, namely A. Nerling (1861–1872) and J. Hesse (1869–1873). Subsequently, a number of additional individuals pursued. The missionaries facilitated the transmission of extensive knowledge about India to Estonia, resulting in the publication of several papers and books. These mostly pertained to the evangelical missionary efforts in India but also encompassed discussions on the caste system, religions, teachings of yoga and Indian classical literature. In 1912, writer Andres Saal made a noteworthy contribution by writing extensive pieces on the Indian epic ‘Mahabharata’ play, and folk wisdom in the literary magazine ‘Olevik’ (‘The Present’) (Embassy of Estonia, New Delhi).

In the early 1800s, the University of Tartu issued numerous publications in Sanskrit. The teaching of Sanskrit began at Tartu University in 1837. K.B Usha, associate professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University in India, who has worked extensively on India-Baltic states relations and runs the Baltic Studies, says

Tartu University was home to many world-famous orientalists of Estonia Baltic-German origin. Among them, the renowned scholar of Indian studies Leopold von Schroeder and Buddhologist and Philosopher Hermann Graf Keyserling deserve special mention. Estonian Buddhists played an important role in spreading Buddhism in Europe. The first person who disseminated Buddhism in Estonia was Karlis August M. Tennisons (1873-1962), also known as the Sanghraja of Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia, the Buddhist Archbishop and the Baltic Mahatma. (Usha 2015: 99)

After regaining independence, the Baltic states showed interest in India’s culture, philosophy, myths, etc., which led to the establishment of oriental studies where Indology became one of the important branches of the Baltic Oriental Studies (Usha 2015). In 1996 a separate India studies centre was established at Vilnius University, operating within the Department of Oriental Studies. The 2nd Regional Conference of Central and Eastern Europe on India Studies (CEEIS) was held at Vilnius University in August 2006, with the support of the Indian Council of Cultural Relations (ICCR). The Oriental Centre of Vilnius University, in collaboration with the Lithuanian Embassy, has published a collection of 108 frequently-used Sanskrit words in the Lithuanian language (Pandey 2023). Academic collaboration between Indian and Baltic states universities has been established and various MOUs signed between them. Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), India’s top-ranked university known for academic excellence in the social sciences, runs a course on the Baltic states and the Baltic Sea Region. Since the establishment of the course in 2009, several dozen theses and dissertations have been written related to Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania ranging from economy, security, identity and gender. JNU has also signed several exchange programme agreements with Lithuanian and Latvian universities. Other than JNU, Dev Sanskrit Vishwavidyalaya in Haridwar has also established the Center for Baltic Culture and Studies (CBCS) to foster and promote the cultural activities of both India and the Baltic countries.

The growing cultural relations and understanding between India and the Baltic states have provided a suitable environment for Indian students pursuing their higher education in the Baltic states. In the last ten years, the number of students of Indian origin has increased in the Baltic states, particularly Latvia. According to the official statistics of Latvia, in 2014 the number of Indian students in Latvia was 164 which increased to 2643 in 2023 (Official Statistics of Latvia 2023; LSM+ 2024). Lithuania has also seen a huge rise in the number of Indian students, increasing from 37 in 2011 to 357 in 2014 and to 1000 in 2022 (Sinha 2015). Despite its rise as a technological hub among the Baltic states, Estonia is the least preferable destination for Indian students as only 138 were studying there in 2022 (Ministry of External Affairs, India 2022). Students from the Baltic states also acknowledge the educational standard of India and show a keen interest in studying at Indian universities. In 2020, there were around 900 Estonians, 4000 Latvians and 2000 Lithuanians studying in Indian universities (Jain 2023).

Political cooperation between India and the Baltic states

In the 1920s and 1930s, the Baltic states surfaced for the first time as an independent nation on the world map. In 1921, India recognised the Baltic states for the first time, when they became a member of the League of Nations (Usha 2015: 103). In 1991, after the Soviet disintegration, the Baltic states regained their independence and India established diplomatic relations with them in 1992. In 2008, after 15 years of diplomatic relations, Lithuania was the first Baltic nation to open its embassy in India; Latvia and Estonia followed in Lithuania’s footsteps and opened their embassies in 2013 and 2015 respectively. On the occasion of its 30th year of diplomatic relations with the Baltic states, India opened its first embassy in Estonia in 2021 (ERR 2020), its second embassy in Lithuania in 2023 (LRT 2023) and intended to open its embassy in Latvia in 2024 (WION 2023).

Since 1992, various bilateral agreements have been signed between India and the Baltic states. As shown in Figure 1, the first agreement India signed with Estonia and Latvia was the Declaration of Principles of Cooperation in 1995, and it signed its first agreement with Lithuania in 1993 with the Agreement on Trade and Economic Cooperation. Since then, India and the Baltic states have signed various agreements ranging from economic, technology, cybersecurity and agriculture. The latest MOU Estonia signed with India was in 2019 for the cooperation of cybersecurity and visa waiver on diplomatic passports. India’s latest agreement with Latvia was in 2013 on the prevention of double taxation and tax evasion. Lithuania’s latest agreement with India was in 2019 for an agricultural work plan.

Figure 1: India’s bilateral agreements with all three Baltic states

|

India-Estonia |

|

|

India-Latvia |

|

|

India-Lithuania |

|

Source: Collected by Author from various sources (Embassy of India, Tallinn, Embassy of India, Stockholm, Ministry of External Affairs, India, Embassy of India, Vilnius).

As highlighted in Figure 2, many high-level visits and interactions between government officials have also taken place. The first visit from Estonia to India was by Minister of Foreign Affairs Trivimi Velliste in October 1993, and the most recent visit was paid by Estonia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Margus Tsahkna on 21–23 February 2024. From Latvia, the first high-level visit to India was paid by President Guntis Ulmanis in October 1997, and the latest visit was paid by State Secretary of Ministry of Foreign Affairs Gunda Reire in March 2023. From Lithuania, the first official visit to India was paid by Prime Minister Adolfas Slezevicius in September 1995, and the latest visit was paid by Lithuanian Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis in April 2022. From India, the first official visit to Estonia and Lithuania was paid by Minister of States for External Affairs Shri Salman Khurshid in August 1995, and the latest visit was paid by India’s Vice President Hon’ble Shri M. Venkaiah Naidu in August 2019, the first-ever high-level visit (from India) to the three Baltic countries (The Economic Times 2019).

Figure 2: Bilateral visit between India and the Baltic states

|

India-Estonia |

|

|

By India |

By Estonia |

|

|

|

India-Latvia |

|

|

By India |

By Latvia |

|

|

|

India-Lithuania |

|

|

By India |

By Lithuania |

|

|

Source: Collected by Author from various sources (Embassy of India, Tallinn, Embassy of India, Stockholm, Ministry of External Affairs, India, Embassy of India, Vilnius)

Even though the number of mutual official visits suggests dynamic development of relations, it is disappointing to note that, despite maintaining thirty years of diplomatic relations, the cooperation between India and the Baltic states has not reached its potential due to their limited engagement and the absence of a diplomatic representative from India in the Baltic states. India's engagement with the Baltic nations appears to align with the evolving dynamics of its foreign policy. The Baltic countries exhibit not just quick economic growth but also possess advanced technological capabilities. They aim to establish a unique identity that goes beyond the EU and NATO, built upon their capabilities in economic, scientific, technological and digital governance fields.

The current prime minister of India has started emphasising the engagement with the small states of the Eastern European region. In an interview with a news channel (Times Now), Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi highlighted his policy towards small states by saying, ‘we also need to understand that we shouldn’t consider smaller countries insignificant. . . . The small countries of the world are as important as big nations’ (Modi 2016). The recent visit of India’s Vice President M. Venkaiah Naidu to all three Baltic states has established the foundation for increased collaboration between India and the Baltic region by offering a chance to explore potential areas for cooperation in the future. These countries view India as an untapped market, whereas India seeks innovative technologies and e-governance from this region.

Economic relations between India and the Baltic states

India and the Baltic states are situated in different parts of the world, and are indeed distinct in many ways; however, there are some similarities. In geography, culture and language, both India and the Baltic states are very diverse. The Baltic states are part of the second largest democracy (the EU) and India is the largest democracy in the world. Cultural diversity is a vital stronghold of the Baltic states as it is for India. Though there is a historical cultural link between India and the Baltic states, economic relations between India and the Baltic states have been fairly limited.

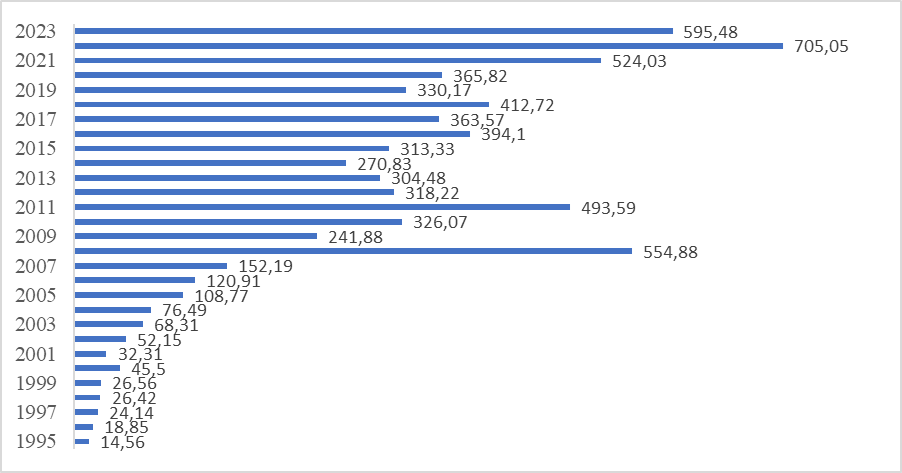

Figure 3: Total Trade between India and the Baltic States in (1995–2023)

Source: Calculated by author based on Export Import Data Bank of OECD and UN Comtrade Database (In US million dollars)

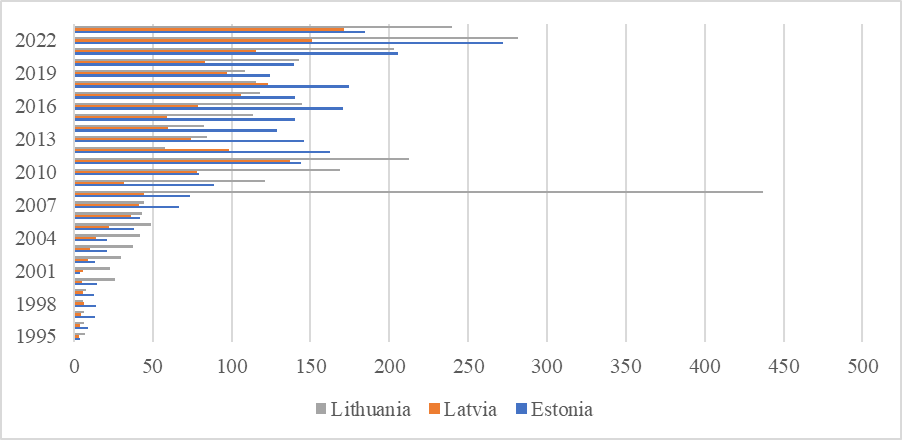

Figure 4: Bilateral Trade between India and All Three Baltic States (1995–2023)

Source: Calculated by author based on Export Import Data Bank of OECD and UN Comtrade Database (In US million dollars)

Two vital cooperation platforms remain significant for the Baltic states’ economic relations with India: the EU and the Baltic Sea Region (BSR). India has fairly good economic relations with many BSR nations and the EU is one of the largest investors in India. As shown in Figure 3 & 4, trade between India and the Baltic states has increased manifold over the period, and overall trade between India and the Baltic states has doubled in the last ten years. Trade between India and the Baltic states stood at USD 595.48 million in 2023. In 2022, trade between India and the Baltic states was USD 705.05 million and USD 524.03 million in 2021, which shows the constant growth of trade between India and the Baltic states.

India-Estonia

The bilateral trade between Estonia and India has grown gradually since the establishment of diplomatic relations. Trade data from the OECD and the UN suggests that bilateral trade between India and Estonia was USD 184.54 million in 2023, USD 272.11 million in 2022 and in 2021 stood at USD 205.71 million. Since 1996, trade between India and Estonia has grown by an average of 26.24 percent every year. In 2023, Estonia imported USD 95.98 million worth of products from India and the top products were electrical machinery and equipment, organic chemicals, and articles of iron & steel. In the same year, Estonia exported USD 88.55 million worth of products to India. The top products that India imports from Estonia are mineral fuel and mineral oil, wood pulp, electric machinery and equipment, and articles of wood and wood charcoal (OECD and UN Comtrade Database).

Since Estonia has a good capacity in cybersecurity, information technology and blockchain, India is looking for collaboration in these fields to enhance their capabilities. Estonia is also trying to attract IT companies to establish data centres in Estonia (Embassy of India 2024). In 2018, Indian business tycoon Mukesh Ambani became an e-resident of Estonia and, along with Union IT Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad (The Economic Times 2018), set up a research centre in Estonia to analyse and understand the digital society of the Baltic nation and what benefits India can extract (Embassy of Estonia, New Delhi 2019). Apart from the IT sector and blockchain, India and Estonia are also looking into potential collaboration on green energy tech including green hydrogen and wind energy. In a recent visit to India, Tiit Risalo, Estonia’s economy minister, expressed interest for close cooperation with the Adani group and the Indian government on the research and development of green hydrogen (Mattoo 2024).

India-Latvia

The bilateral trade between India and Latvia was USD 151.11 million in 2022, which increased 13.18 percent by 2023 and stood at USD 171.03 million. The major products exported from India to Latvia in 2023 were pharmaceutical products, rubber tires, organic or inorganic compounds of precious stone and metals. In the last twenty-five years, the exports of India to Latvia have enlarged at yearly average of 20.18 percent, from USD 3.34 million in 1995 to USD 171.03 million in 2023. In 2023, Latvia exported USD 49.08 million worth of products to India. The major products India imports from Latvia are iron and steel, edible vegetables and certain roots and tubers, and wood and wood charcoal (OECD and UN Comtrade Database).

India-Lithuania

Lithuania is India’s largest trading partner among the Baltic states. Lithuania’s trade with India in 2023 stood at USD 239.91 million. This is -14.87 percent less than the bilateral trade between India and Lithuania in 2022, which was USD 281.83. In 2023 Lithuania imported USD 139.99 million worth of products from India. The top products India exported to Lithuania were electric machinery and equipment, fish and other seafood, chemical products, iron & steel, and pharmaceutical products. Like Estonia and Latvia, Lithuania’s exports to India grew from USD 2.93 million in 1996 to USD 99.92 in 2023. Lithuania’s exports to India were recorded at the highest level in 2008 when it saw a jump of 2,945 percent compared to 2007 (see figure 4). This was due to India’s import of fertiliser, driven by the global fertiliser crisis caused by high oil prices and the US shift towards biofuel corps. This situation forced countries like India and China to stock fertiliser in large quantities to guarantee their food stocks (Vidal 2008). The top products Lithuania exports to India are iron & steel, salt, sulphur, lime, cement, electrical machinery and equipment, coffee, wood and wood charcoal (OECD and UN Comtrade Database).

Lithuania invites Indian companies to invest in pharmaceuticals, biotechnology and life sciences and the country is expecting a boom in the coming years. In a 2019 joint press conference with Indian Vice President Venkaiah Naidu, Lithuanian President Gitanas Nauseda asked Indian companies to invest in those areas. At the same time, they agreed to ‘enhance cooperation in areas such as agriculture, food processing, information technology, financial services, and also financial technology’ (Delfi 2019).

Trade data indicates that India’s exports to the Baltic states have grown rapidly, especially after the Covid pandemic. India and the Baltics both continue to diversify their economic partnership. India, as the fastest growing economy with a young and skilled workforce, can gain access to new markets and technology from the Baltic states. The Baltic states, in turn, have a strong track record of innovation and a focus on digitisation and e-governance. Meanwhile, the Baltic countries can benefit from India’s large and growing economy.

Changing geopolitics and India-Baltic states’ relations

Recent confrontations like the US-China trade war, the India-China Border clash, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and Israel-Hamas conflict have brought major changes in world politics (Tchakarova 2023). In this changing geopolitical scenario, India has also renewed its attention to Europe. India is not only reaching out to big nations but also to small nations including the Baltic states. India’s Europe policy is still focused on engaging both the European Union (EU) as a whole and its individual member states separately. However, there is also growing interest in building cooperation efforts in certain sub-regions, such as central and Eastern European countries (Xavier & Kumar 2017).

With the rise of China as a threat perception in the West, the Baltic states became more cautious regarding China’s role in the Baltics. A few years ago, it would have been impossible to imagine that Lithuania would have emerged as one of China's most vocal critics. Lithuania’s relationship with China has gone from wrong to worse due to recent steps of Lithuania, such as leaving the 17+1 format because Vilnius believes that Beijing is trying to use the format to divide the European states and strengthen its influence in Europe. Some of Lithuania’s actions include excluding Huawei in the development of 5G technology on the recommendations of the 2020 national threat assessment, passing a motion to condemn China’s policy against Uyghur Muslim and slamming Beijing for clamping down on Hong Kong protesters (Andjauskas 2020; Andjauskas 2021). The tension culminated when Lithuania allowed the Republic of China (Taiwan) to open a representative office in Lithuania. Allowing the Republic of China (Taiwan) to open a de facto embassy in Vilnius using the name Taiwan has irked Beijing (Andjauskas 2022). In response to this step China recalled its ambassador in August 2021 and downgraded its relations to the level of charge d’affaires – a rank below ambassador (LRT 2021).

Besides diplomatic measures, China has also taken economic measures to punish Lithuania. Lithuania’s direct trade with China only accounts for 1% of its total trade; however, Lithuania’s export base economy is home to several companies that make products like laser, furniture, glass, food and clothing for multinational companies that sell to China (LRT 2022). China steadily pushed the pressure button on Lithuania by pressuring multinational companies to avoid using parts and supplies from Lithuania or they would no longer be welcome in the Chinese market. As a result of Chinese economic retaliation, many German firms involved in peat, lasers, car parts and high-tech sectors have suggested that they may have to shut factories in Lithuania. The German Baltic Chambers of Commerce warned the Lithuanian government in a letter that the German investors might need to close their services in Lithuania until there is ‘a constructive solution to restore Lithuania-Chinese economic relations’ as they cannot receive the necessary components from China for production (Sytas & O’Donnell 2022).

China’s confrontation with Lithuania over Taiwan policy, and China’s deadly clash with India, drove Baltic states closer to India (Marjani 2022). Also, cyber-attacks by Chinese hackers on the Baltic states and India forced them to cooperate closely to counter China’s cyber threat. India and Estonia have united to counter cyber threats originating from China and are aiming to strengthen their cybersecurity cooperation. Estonian Defence Minister Hanno Pevkur has accused the Chinese government of recruiting experts to carry out cyberattacks. ‘Every country ready to fight this evil is more than welcome in Estonia’, he said in Times Now, expressing his invitation to the Indian defence delegation (Chowdhury 2024). The collaboration between Estonia and India signifies a courageous move towards a better-protected digital future in the critical cyber warfare arena. This strategic alignment enables both parties to cooperate and enhance their defensive capabilities against China's ongoing cyber threat.

In recent years many European nations like France, Germany, the UK, etc have unveiled their Indo-Policy strategy. In 2021, the EU also officially released the joint communication to the European Parliament about the EU strategy for cooperation in the Indo-Pacific (European Commission 2021) to counter China with the creation of multilayer cooperation with like-minded Indo-Pacific partners such as Japan, South Korea and Australia (Pugliese 2024). The Baltic states have also shown their interest in the Indo-Pacific; Lithuania in particular has released an Indo-Pacific Strategy document in 2023 which shows Lithuania’s strategy response to ‘global geopolitical shifts that have a direct effect on our country and the EU’ (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Lithuania 2023). These ‘shifts’ comprise the China-Russia ‘no limits’ collaboration, which includes threats to topple the global rules-based system, Russia's protracted invasion of Ukraine and the consequent growth and change of NATO’s force posture, and the consequences for NATO and its partners (Garrick & Andrijauskas 2023). Lithuania emphasises India’s importance in its Indo-Pacific strategy to maintain the rules-based order and for resilient economic growth. In an interview with Indian Media while visiting India in November 2023, Lithuanian Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Egidijus Meilunas highlighted India’s importance in their Indo-Pacific strategy, saying:

India has a prominent role to play in our strategy. We will aim at mutually beneficial cooperation with India, the largest democracy and one of the largest economies in the world. This year, with the opening of the Indian embassy in Vilnius, we witnessed a very positive momentum in our bilateral relations. We have to work together to foster our economic and trade relations, very glad that our trade turnover and exports are increasing. I am confident that in due time will [sic] be considering about the developing our bilateral security and defence dialogue with India. (Sharma 2023)

In the changing geopolitical dynamic, both India and the Baltic states are trying to maximise the benefit by cooperating closely. They are working together on their shared desire to maintain the multilateral rules-based order and increase the representation of international institutions. Their interest in changing international institutions is most visible in the UN Security Council; India wants a permanent seat, while the Baltic states want better representation in both permanent and non-permanent membership categories. Their mutual commitment to upholding the rules and regulations in the maritime domain is quite visible. Both parties are mutually concerned with guaranteeing maritime security and upholding the freedom of navigation in separate regions: the Baltic Sea and the Indo-Pacific (Adomenas 2022; Rajiv 2018: 2).

In the Eurasian landmass China is becoming a prominent player and growing relations between China and Russia have alarmed the Baltic states. The growing naval drills by Russia-China in the Baltic Sea Region have also alarmed the Baltic states and created strategic challenges and security dilemmas for the Baltic states (Scott 2018). ‘This economic leverage translates to political leverage able to be exerted on the Baltic states by China’ (Scott 2018: 25) to weaken solidarity within the grouping and in the EU. In addition to investment from the EU, the Baltic states are seeking to attract external investment and to establish themselves as regional transport hubs. India is an appealing option to counter Chinese investment due to its support for the International North-South Transport Corridor, which can connect the Baltic Sea region with the Indian Ocean region. Due to its strategic location, Latvia sees itself as a conduit between both the European Union and the Russian hinterland. Latvia seeks increased investment and commerce from India, as well as access to its all-weather ports. During his 2017 visit to India, Latvian Prime Minister Maris Kucinskis said that ‘Latvia is focusing on the transport and logistics. . . . Building direct link [sic] and establishing direct contact through ports will establish a close relationship between the two countries’ (Business Standard 2017). Lithuania also discussed the advantages of Klaipeda port with India, considering the expertise of India in port infrastructure development and Lithuania’s location as a gateway to the Eastern European Region (PIB 2023).

Although the relations between India and the Baltic states are growing, at the same time Baltic and Western leaders have shown irritation over India’s refusal to join international condemnations of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and its repeated abstention in the UNSC’s (United Nations Security Council) votes on the issue of Russia-Ukraine War (Mohan 2022). Since the fall of the USSR, Indian foreign policy has largely been dominated by the strategic autonomy discourse. However, Russia’s aggression in Ukraine forces India to strike a balance between its long-term trusted partner Russia and the growing and important relationship with the US and the Quad. India firmly believes that it is best to avoid provoking Moscow since doing so could drive Russia into China’s sphere of influence. For India, the worst-case scenario would be a formal alliance between Russia and China, in which China might exert control over Russia's engagement with India. India is already in a border dispute with China, and the current standoff with China has resulted in the deployment of a large number of troops and heavy weapons along the border with China in the Himalayan region; additionally, Russia is India's largest weapon supplier; antagonising Russia in this scenario could prove fatal for New Delhi (Lieberherr 2022). Though the EU and Baltic states have shown discomfort with India’s position on Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, they agree to disagree on this aspect. Baltic states understand the circumstances that force India to not take a stand in the Russia-Ukraine war and even know that India will maintain its position of non-alignment. Therefore, India’s Relations with the Baltic states will remain intact despite India’s position on Russia’s aggression against Ukraine.

Conclusion

The cooperation between India and the Baltic states has been largely driven by political, economic and cultural factors. Since the establishment of the diplomatic relations, all three factors have greatly contributed to bringing these two different regional states together, but the cultural link between India and the Baltic states is the vital factor driving their cooperation. In the last three decades, the relations between India and the Baltic states have not reached the position they could have due to their geographical distance and the lack of will for diplomatic engagement from both sides which hindered cooperation. However, the recent geopolitical changes in world politics and the rise of China brought India and the Baltic states to work more closely together. Their democratic ethos and belief in rule and value-based order are also determining factors that drive the relations. Cultural similarity and increasing people-to-people engagement play an important role in swinging the relations upward. The Baltic states' rise in economic, technological and digital innovation and governance have also increased India’s interest where India can try to learn and gain a foothold.

In the coming decade, India will be one of the top three largest economies in the world and the Baltic states want to divert their business from China to India as many Western countries are already doing. The Baltic states see India as a tool to counter China in the Baltic Sea Region, Central Asia and Indo-Pacific region. At the same time, India is also convincing the EU and other Western nations to recognise the threat of China not only to India but also to the current international order. India also wants to develop a greater Indo-Baltic engagement on regional and international issues which can allow India to have a more diverse perspective in Eastern, Central and Northern Europe. In an era of geopolitical transformations, the security of the Baltic region, South Asia region and Indo-Pacific region are interconnected. It is increasingly crucial to collaborate closely to maintain international law and develop the ability to address direct and indirect threats, whether they arise in the Indian Ocean region, the Indo-Pacific region or the Baltic Sea region.

***

Funding

No funding information.

Acknowledgements

The Baltic Sea Area was new to me when my PhD Supervisor introduced it to me during the M.Phil. coursework, So, I would like to thank my Supervisor, Dr. K.B. Usha who always encouraged me to find new gaps in the Baltic Sea area. The author is also thankful to the CEJISS editors and technical team, and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback and comments on the earlier version of this manuscript.

Dr. Karan Kumar is an early career scholar with a Doctoral Degree in Russian and Central Asian Studies, from Jawaharlal Nehru University, India. His Doctoral thesis investigated the development of the Baltic Sea Region through the lens of identity, security and economic dimensions. He has also submitted an M.Phil. thesis on NATO’s expansion and its implication on the Baltic States. He was awarded with Erasmus+ Fellowship for an exchange programme to visit as a research fellow at Kaunas Technology University, Lithuania, in 2018; Moreover, he holds a master's degree in International Relations from Pondicherry University, India. His area of research concentrated on the Baltic Sea Region, the Security Dynamics of Russia and NATO’s Expansion, and India, China and Baltic States Bilateral Relations.

References

Adomenas, M. (2022): About the Strength of the Weak. Thirteen Theses on the Assumptions and Principles of the New Foreign Policy of Lithuania. LRT, 06 December, <accessed online: https://www.lrt.lt/naujienos/nuomones/3/1837798/mantas-adomenas-apie-silpnuju-stiprybe-trylika-teziu-apie-naujosios-lietuvos-uzsienio-politikos-prielaidas-ir-principus>.

All India Association of Industries (AIAI) (2015): Lithuania Seeks Investment Cooperation with India. 30 April, <accessed online: https://aiaiindia.com/lithuania-seeks-investment-cooperation-with-india/>.

Andrijauskas, K. (2020): Sino-Lithuanian Relations in 2020: Shedding the Masks? Eastern Europe Studies Centre, 30 November, <accessed online: https://www.eesc.lt/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Sino-Lithuanian-Relations-in-2020-Shedding-the-Masks-Konstantinas-Andrijauskas.pdf>.

Andrijauskas, K. (2021): Lithuania’s Decoupling from China Against the Backdrop of Strengthening Transatlantic Ties. Eastern Europe Studies Centre, 11 August, <accessed online: https://www.eesc.lt/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/eesc-review-lithuanias-decoupling-from-china-against-the-backdrop.pdf>.

Andrijauskas, K. (2021): The Sino-Lithuanian Crisis: Going Beyond Taiwanese Representative Office Issue. Institut Francais des Relations Internationales, 08 March, <online accessed: https://www.ifri.org/en/briefings-de-lifri/sino-lithuanian-crisis-going-beyond-taiwanese-representative-office-issue>.

Business Standard (2017): India Visit a Turning Point in Bilateral Relations: Latvian PM. 6 November, <accessed online: https://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ians/india-visit-a-turning-point-in-bilateral-relations-latvian-pm-117110601348_1.html>.

Chada, A. (2020): India’s Innovation-Driven Nordic-Baltic Engagement. The Diplomat, 11 November, <accessed online: https://thediplomat.com/2020/11/indias-innovation-driven-nordic-baltic-engagement/>.

Chatterji, S. K. (1967): Balts and Aryans: In Their Indo-European Background. Shimla: Indian Institute of Advance Studies.

Chowdhury, S. (2024): India-Estonia Cyber Security Cooperation to Combat Growing Threat from Chinese Hackers. Times Now, 25 May, <accessed online: https://www.timesnownews.com/world/europe/india-estonia-cyber-security-pact-to-combat-growing-threat-from-chinese-hackers-article-110410893>.

Delfi (2019): President: We hope for More Indian Investment. 19 May, <accessed online: https://www.delfi.lt/en/business/president-we-hope-for-more-indian-investment-82012891>.

Development is my conviction, it's my commitment: PM Narendra Modi, 27 June 2016, <accessed online: https://www.narendramodi.in/pm-modi-s-exclusive-interview-with-times-now-full-transcript-arnab-goswami-497175>.

Dutta, A. (2019): India-Baltic Relations: Review of Vice President’s Visit to the Region, Indian Council of World Affairs, 15 April, <accessed online: https://icwa.in/show_content.php?lang=1&level=3&ls_id=3240&lid=2497>.

Embassy of Estonia, New Delhi (2019): Reliance Industries Opens Research Centre in Estonia. 19 May, <accessed online: https://newdelhi.mfa.ee/reliance-industries-opens-research-center-in-estonia/>.

Embassy of Estonia, New Delhi (2024): Cultural Relations: Estonia and India. 14 May, <accessed online: https://newdelhi.mfa.ee/cultural-relations/>.

Embassy of India, Sweden & Latvia (2024): Indo-Latvia Trade. 16 May, <accessed online: https://www.indembassysweden.gov.in/page/indo-latvian-trade-main/>.

Embassy of India, Tallinn (2024): India-Estonia Bilateral Relations, 19 May, <accessed online: https://www.indembassytallinn.gov.in/bilateral-brief.php>.

Embassy of India, Vilnius (2024): Fact Sheet. 18 May, <accessed online: https://www.eoivilnius.gov.in/fact-sheet.php>.

ERR (2020): India to Open Embassy in Estonia. 16 May < accessed online: https://news.err.ee/1223902/india-to-open-embassy-in-estonia>.

European Commission (2021): Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council: The EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific, 16 September, <accessed online: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/jointcommunication_2021_24_1_en.pdf>.

Finnemore, M. & Sikkink, K. (1998): International Norms Dynamics and Political Change. International Organization, 52(4), 887–917.

Garrick, J. & Konstantinas A. (2023): Why Does Lithuania Need an Indo-Pacific Strategy? The Diplomat, 17 May, <accessed online: https://thediplomat.com/2023/10/why-does-lithuania-need-an-indo-pacific-strategy/>.

Govardhan (2015): Influence of Gandhian Principles of Nonviolence in the Singing Revolution (Sajudis Movement) of Lithuania. International Journal of Applied Social Science, 2(5&6): 146-156.

Grare, F. & Manisha R. (2021): Moving Closer: European Views of the Indo-Pacific. European Council on Foreign Relations, 2 September, <accessed online: https://ecfr.eu/wp-content/uploads/Moving-closer-European-views-of-the-Indo-Pacific.pdf>.

Jain, A. (2023): Baltic Expats in India Shatter Colonial Images of the Country and Discover Spiritual Life. The Baltic Times, 4 October, <accessed online: https://www.baltictimes.com/baltic_expats_in_india_shatter_colonial_images_of_the_country_and_discover_spiritual_life>.

Keohane, R. O. (1984): After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

Keohane, R. O. & Nye J.S. (1977): Power and Interdependence: World Politics in Transition. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Kuo, A. M. (2023): China and the Baltics. The Diplomat, 27 May, <accessed online: https://thediplomat.com/2023/09/china-and-the-baltics/>.

Lieberherr, B. (2022): Russia’s War in Ukraine: India’s Balancing Act. Centre for Securities Studies, <accessed online: https://css.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/pdfs/CSSAnalyse305-EN.pdf>.

LRT (2021): China Recalls Ambassador from Lithuania. 10 August, <accessed online: https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1466061/china-recalls-ambassador-from-lithuania>.

LRT (2022): Lithuania Counts on Foreign Partners as German Investors Sounds Alarm Over China’s Pressure. 4 October, <accessed online: https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1570020/lithuania-counts-on-foreign-partners-as-german-investors-sound-alarm-over-china-s-pressure>.

LRT (2023): Indian Embassy Opens in Vilnius. 16 May, <accessed online: https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1954504/indian-embassy-opens-in-vilnius>.

LSM+ (2024): Latvia Radio Probes Study Schemes for Overseas Students. 3 October <accessed online: https://eng.lsm.lv/article/features/features/07.06.2024-latvian-radio-probes-study-schemes-for-overseas-students.a557101/>.

Marija, Gimbutas (1963): The Balts. London: Thames and Hudson

Marjani, Niranjan (2022): The China Factor in India’s Engagement with Europe. The Diplomat, 13 April, <accessed online: https://thediplomat.com/2022/04/the-china-factor-in-indias-engagements-with-europe/>.

Ministry of External Affairs, India (2022): Estimate Data of Indian Students Studying in Abroad. 16 September, <accessed online: https://www.mea.gov.in/Images/CPV/lu3820-1-mar-25-22.pdf>.

Ministry of External Affairs, India (2024): India Latvia Relations. 16 May < accessed online: https://www.mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/Latvia_2015_07_02.pdf>.

Ministry of External Affairs, India (2024): India-Lithuania Bilateral Brief. 13 May, < accessed online: https://www.mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/Ind_Lithuania_2020.pdf>.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Lithuania (2023): Strategic Guidelines for the Indian and Pacific Region of Lithuania for Safer, More Resilient and Economic Growth Future. 28 May, <accessed online: https://urm.lt/uzsienio-politika/lietuva-regione-ir-pasaulyje/lietuvos-bendradarbiavimas-su-indijos-ir-ramiojo-vandenynu-regionu/544>.

Mohan, Raja C. (2022): Ukraine and India’s Strategic Autonomy: The Russian Twist. Institute of South Asian Studies, 4 March, <accessed online: https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/ISAS_Brief_910-.pdf>.

Nye, J. S. (2004): Soft Power. New York: Public Affairs.

OECD (2024): Bilateral Trade in Goods by Industry and End-use, <accessed online: https://data-explorer.oecd.org/

Official Statistics of Latvia (2023): Mobile Students from Abroad in Latvia. 3 October, <accessed online: https://stat.gov.lv/en/statistics-themes/education/higher-education/8098-mobile-students-abroad-latvia?themeCode=IG>.

Pandey, S. (2023): In Lithuania We Take Pride in Having Close Connection with Sanskrit: Envoy Diana Mickeviciene. ANI, 27 March, <accessed online: https://www.aninews.in/news/world/asia/in-lithuania-we-take-pride-in-having-close-connection-with-sanskrit-envoy-diana-mickeviciene20230327221114/>.

PIB (2023): India and Lithuania Discuss Maritime Relations, Press Information Bureau, 20 April, <accessed online: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1979216>.

Pugliese, G. (2024): The European Union and an “Indo-Pacific” Alignment. Asia-Pacific Review, 31(1),17-44.

Rajiv, S. (2018): Bridging the Gap Between India and the Baltics, International Centre for Defence and Security, 1-7.

Scott, D. (2018): China and the Baltic States: Strategic Challenges and Security Dilemmas for Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. Journal of Baltic Security, 4(1), 25-37.

Sharma, S. (2023): India to Play a Prominent Role in our Indo-Pacific Strategy: Lithuania’s Egidijus Meilunas. The Economic Times, 29 May, <accessed online: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/india-to-play-a-prominent-role-in-our-indo-pacific-strategy-lithuanias-egidijus-meilunas/articleshow/105562998.cms?from=mdr>.

Sibal, S. (2023): India to Open Embassy in Latvia, Move Welcomed. WION, May 16, < accessed online: https://www.wionews.com/india-news/india-to-open-embassy-in-latvia-move-welcomed-662330>.

Sinha, K. (2015): Lithuania Sees Huge Rise in Indian Students. Times of India, 4 October, <accessed online: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/europe/lithuania-sees-huge-rise-in-indian-students/articleshow/47996731.cms>.

Sytas, A. & O’Donnell, J. (2022): German Big Business Piles Pressure on Lithuania in China Row. Reuters, 5 October, <accessed online: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/german-big-business-piles-pressure-lithuania-china-row-2022-01-21/>.

Tchakarova, V. (2023): Shifting Sands: Navigating the New Geopolitical Landscape in 2024. Observer Research Foundation (ORF), 11 May, <accessed online: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/shifting-sands-navigating-the-new-geopolitical-landscape-in-2024>.

The Economic Times (2018): Mukesh Ambani Sets up Estonian JV foe E-Governance; Takes up E-residency. 19 May, <accessed online: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/company/corporate-trends/mukesh-ambani-sets-up-estonian-jv-for-e-governance-takes-up-e-residency/articleshow/66497754.cms>.

The Economic Times (2019): Venkaiah Naidu to Visit Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia From August 17-21: MEA. 12 May, <accessed online: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/venkaiah-naidu-to-visit-lithuania-latvia-estonia-from-august-17-21-mea/articleshow/70679247.cms?from=mdr>.

Trade with Estonia (2024): Estonian Business Delegation Advances Export Prospects in India: A Strategic Move to Expand Global Sales. 19 May, <accessed online: https://tradewithestonia.com/estonian-business-delegation-advances-export-prospects-in-india-a-strategic-move-to-expand-global-sales/>.

UN Comtrade Database (2024): Trade Data, <accessed online: https://comtradeplus.un.org/TradeFlow>.

Usha, K. B. (2015): The Evolving Relations Between India and the Baltic States. Lithuanian Foreign Policy Review, 27, 83–109.

Vidal, J. (2008): Soaring Fertiliser Prices Threaten World’s Poorest Farmers. The Guardian, 12 August, <accessed online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2008/aug/12/biofuels.food>.

Waltz, K. N. (1979): Theories of International Politics. Berkeley: Addison-Wesley.

Wendt, A. (1999): Social Theory of International Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Xavier, C. & Arushi K. (2017): Reviving Indo-European Engagement in the Baltic. Carnegie India, 14 May, <accessed online: https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2017/06/reviving-indo-european-engagement-in-the-baltic?lang=en¢er=china>.