Abstract

The paper aims to analyse Hungary’s evolving foreign policy in a changing world order since the politico-economic regime change of the early 1990s, but with the main focus on relations with the member states of the BRICS group since the initiation of Hungary’s ‘Global Opening’ policy in 2011. As such, the paper aims to offer a comparative overview of Hungary’s engagements with the five core members of the BRICS. By following the theory of poles and paying attention to the changing world order, Hungary’s foreign policy is critically examined to pave the way for a geopolitical analysis of bilateral relations with the BRICS members. Trade, security and soft power (culture and education) will be analysed in more depth and scrutiny.

Keywords

Introduction and theoretical background

Following the demise of the Soviet Union, the ‘unipolar moment’ was defined by the United States’ unrivalled dominance, both militarily and culturally, contrasting the bipolar world order that permeated the Cold War period. Kenneth Waltz’s neorealist theory of polarity (Waltz 1979; Buzan 2013) seems to be a key framework for understanding these shifts, as it classifies global orders based on the number of major powers, or poles, that dominate economically, militarily and technologically. According to this theory, a unipolar system like the one seen after the Cold War is characterised by one superpower, while bipolar and multipolar systems have two or more major powers. Although material factors like military budgets are often prioritised in this analysis, soft power elements can also play a significant role in defining polarity (Vörös & Tarrósy 2024).

Waltz argued that bipolar systems, such as the US-Soviet setup during the Cold War, are the most stable because they create a clear balance of power, reducing the likelihood of major interstate conflict (Waltz 1979). This perspective was appealing to both Washington and Moscow during the Cold War, as it allowed them to dominate global affairs. However, Waltz viewed unipolar systems as inherently unstable due to the absence of counterbalancing forces, which could encourage other states to push back against the dominant power. Critics like Huntington, however, disagreed, arguing that in a unipolar world, the dominant power can maintain its supremacy unchallenged for an extended period (Huntington 1999). The post–Cold War era, sometimes described as ‘non-bipolar’ due to a lack of clear neorealist consensus, saw the US retain its hegemony, but growing challenges began to emerge.

As global dynamics have shifted, the emergence of regional powers such as China and the reassertion of Russia have signalled the reemergence of multipolarity, with some scholars pointing to the rise of tripolarity involving these three powers (Motin 2024). By the early 2000s, it became apparent that the United States was reluctant to maintain its previous unipolar stance, leading to what some scholars have described as a post-hegemonic, multipolar world order (Tálas 2021). Emerging states, including BRICS nations, seem more inclined toward fostering a multipolar system, which allows them to assert regional influence while countering US dominance. This potential for global multipolarity, where middle powers and regional actors challenge the interests of the United States of America, continues to reshape international relations today (Vörös & Tarrósy 2024).

In this paper, three research questions (RQs) will be investigated. The primary research question, and thus the most critical, is RQ1: ‘What are Hungary’s relations with members of the BRICS, and how has Hungary been re-positioning itself amidst new geopolitical challenges?’ This question is central to understanding Hungary’s evolving role within the shifting global landscape and its strategic engagement with BRICS countries. The other two questions, RQ2: ‘What are the power dynamics behind the changing international arena that contribute to the positioning of the BRICS?’ and RQ3: ‘How has Hungary’s foreign policy changed since the political transition at the beginning of the 1990s?’, are supplementary. Indeed, they provide essential context by examining the broader global dynamics influencing BRICS and Hungary’s historical policy shifts, but they ultimately support the focus of RQ1.

Our methodology embraces a multi-year research project including field projects, archival work and document analysis. Since the publication of ‘Hungary’s Foreign Policy after the Hungarian Presidency of the Council of European Union’ in 2011, we have presented several analyses of the government’s ‘Global Opening’ policy. This was defined as ‘revitalising Hungary’s ties with those parts of the world that have been accorded lesser importance in Hungary’s foreign policy focus in recent years (or have always been outside the scope of that focus); increasing our role in shaping the global agenda and strengthening our activism in meeting global challenges’ (MFA 2011: 9). We aim to show that this paper is a sequel to the previous research we have done on the topic, which can still be considered underexplored. With this in mind, the intention with this piece is to contribute to a better understanding of Hungarian foreign policy in a changing international landscape.

First, the analytical framework is set up within the theoretical context of poles, the importance of geopolitics and the notion of pragmatism in international relations. Then, Hungarian foreign policy regimes will be analysed in the context of BRICS-dynamics in the global arena. Focus will be laid on Hungary’s relations with the core BRICS member states as emerging non-Western actors. Soft power elements such as trade, security and education will be dealt with in more depth and scrutiny. Finally, responses will be offered to the initial research questions together with some concluding thoughts, as well as suggestions for some directions for further research.

Geopolitics and the rise of the BRICS

The essence of contemporary global politics appears to be shaped by the geopolitical tensions between hegemony, represented by the United States, and the power equilibrium sought by China, Russia and other emerging powers. Interestingly, rising powers such as Brazil, South Africa and India have become increasingly influential in global affairs due to their economic growth, military capabilities and strategic positioning. The power transitions from the Global North to the Global South over the last decade have been salient considering the rising powers’ aspirations and growing engagement in global governance (Freddy & Thomas 2023: 395). These countries often pursue their interests through alliances, coalitions and organisations that usually aim to promote common goals, meet common needs and resolve common problems (Tripathi 2010). Some of the common goals entail fostering South-South economic cooperation, political stability and collective security among member states. It is worth mentioning that beyond multilateralism and economic partnerships, these alliances and trans-regional integration initiatives can lead to the challenging of traditional global power structures, the emergence of new power blocs and the shift of alignments in the international system. It is within this context that the BRICS has presented itself as the voice of the Global South (Pant 2023) since its establishment back in 2009. Comprising emerging market economies and developing countries (Xiaolin 2023), this intergovernmental organisation seeks to establish a more equitable and fairer world via the promotion of peace, security, development and cooperation (South African Government 2013).

The burgeoning prominence of BRICS or BRICS+, as some tend to informally call it after its 2024 enlargement, stems from its significance in terms of economic growth and human capital. Following the new membership of Iran, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt and Ethiopia, the bloc is now home to more than 40% of the world’s population. Even more, the BRICS accounts for 37.3% of the world GDP, which is more than double the EU’s share, as the EU does not reach 15% of the global GDP (European Parliament Research Service 2024: 2). Committed to expanding its ranks, reforming major multilateral institutions such as the UN Security Council and the International Monetary Fund and de-dollarising the global financial system, the BRICS seems to be on a quest for greater global influence (European Parliament Research Service 2024). This cherished influence was interpreted by some scholars as a sign of declining Western dominance (Kapoor 2023: 4) and even as an attempt by the bloc to reshape an international system that is unfairly dominated by the US (McCarthy 2024). The recent BRICS summit on 22–24 October 2024 in Kazan further proves that, despite the rejection of the war in Ukraine, aspirations for a transformation of the world order are alive and well, and BRICS could indeed become a key organisation in the (shaping) of the new world order. In the realisation of any such aspiration and in our understanding of power shifts and dynamics across the arena, interpretations play a role, and as Ó Tuathail underscores, most geopolitical production in world politics is of a practical type, where ‘practical geopolitics refers to the spatializing of practices of practitioners of statecraft [. . .] those who concern themselves with the everyday conduct of foreign policy’ (Ó Tuathail 1996: 60). In this vein, we are looking at the changing practices in Hungarian foreign policy, highlighting the presence of pragmatism among the practitioners involved.

Hungary’s foreign policy since the initiation of its ‘Global Opening’

Several of our previous works have explored the major dimensions and critical partnerships within Hungary’s foreign policy matrix since the political transition at the end of the 1980s. We examined new or revisited agenda items alongside certain challenging issues and connections, such as the evolving foreign policy priorities in a dynamic global system (Tarrósy & Vörös 2014), the ‘Global Opening’ policy (Tarrósy & Morenth 2013) and Hungary’s increased pragmatism in fostering relations with countries like China, Turkey, Russia, the Gulf states, Sub-Saharan Africa and other emerging regions. This pragmatism stems from the belief and the idea that the world is changing, that it is becoming multipolar and that in such a structure Hungary must maintain relations with all the key actors – possible poles within this system – to foster its national interests. In particular contexts of either problematic or promising situations, stemming from the Realist school of thought in international relations, any pragmatic policy is shaped ‘in line with the national interest, know[ing] the facts of existing conditions, and pay[ing] special attention to power and its alignments’ (Cochran 2012: 2). In our contemporary international system, such pragmatism can be traced in any of the actors’ behaviour to ‘seek power and calculate interest in terms of power’ (Ibid: 8). Such power-driven interest, especially in today’s heightened global focus on security and securitisation, ‘is always relative to the social and political situation in which foreign policy is crafted’ (Ralston 2011: 79).

In the context of the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine (as of the writing of this paper), it is essential to emphasise that one of Hungary’s most significant foreign policy challenges, as an EU member state, is its relationship with Putin’s Russia. The Hungarian government’s ability to navigate this relationship, leveraging a deep understanding of Russia’s regional geostrategy based on the Primakov doctrine, is crucial (Lechner 2021: 20–21; Sz. Bíró 2014: 41).

Upon our latest detailed analysis of Hungarian foreign policy, we identified the necessity for a more nuanced approach; yet, in the current era of global uncertainties and concerns, Hungarian foreign policy can be characterized—albeit to a limited extent—as pragmatic. Pragmatic, as it replaced the traditional Western orientation of Hungarian foreign policy established following the regime transition by recognizing other options beyond the EU–NATO–immediate neighbourhood policy triangle. This realization has enabled Hungary to implement its strategies regarding the growing East and the prospective South. Although these initiatives lacked coherence and were perhaps unsuccessful and temporary, they demonstrated that relinquishing all our interests in these nations at the conclusion of the 1980s and the onset of the 1990s was a misguided move. Consequently, Hungary should avoid finding itself in the same situation once more. (Tarrósy & Vörös 2020: 132)

At that point, it was evident that this new foreign policy was not consistently pragmatic and, in certain instances, lacked logical coherence. The Orbán administration has aligned its foreign policy with domestic political objectives, resulting in a diminished credibility regarding its international actions (Ibid.).

Now, a few years later, it has to be said that the situation has not changed, and in fact Hungary has further isolated itself from its Western partners, pursuing an increasingly serious anti-Western foreign policy. Pragmatism, as we can state today, would allow and prioritise relations with emerging actors, while maintaining Western partnerships, which would fit much better into the multipolar worldview defined and envisioned by the Hungarian government. A unilateral foreign policy that criticises Western actors – such as in the context of the Russo-Ukrainian War – without condemning Russia is likely a pragmatic miscalculation in terms of power. This approach would pigeonhole the country, hindering its ability to achieve its objectives. One of these aims is to unequivocally use connectivity to become a link between the West and the East. Since 2010, Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz, in coalition with the Christian Democratic People’s Party (KDNP), has consistently emerged victorious in national elections, securing a constitutional majority in parliament in 2010, 2014, 2018 and 2022. Numerous internal and foreign policy changes have been implemented, including managing relations with an array of ‘non-traditional’ partners as part of the new chapters of the Global Opening doctrine (see Puzyniak 2018).

The pivot towards the East, particularly Russia, Central Asia and China, alongside re-engagement with the South, including Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, has dominated Hungary’s foreign policy priorities.

With a heightened focus on international visibility, Hungary has effectively utilised soft power, too, particularly after the introduction of the Stipendium Hungaricum state scholarship in 2013 (see Császár et al. 2023). This initiative, with a focus on China-Hungary educational relations (Tarrósy & Vörös 2019), exemplifies Hungary’s active foreign policy in regions at Europe’s periphery, Asia and certain African countries, as well as in neighbouring nations and across the diaspora (Kacziba 2020: 82). However, this aspect of Hungary’s foreign policy is not widely recognised within its society, where more emphasis is placed on government protection and securitisation schemes addressing refugee flows, energy dependency and the ongoing war in the country’s immediate vicinity.

As we can see, for some time, pragmatism at least at a rhetoric level has been a salient feature of Hungarian foreign policy, which could also enhance its neighbourhood policies. One prime example of this, based on security considerations of the broader macro region, coupled with shared historical ties, intercultural connections and economic interests with neighbouring countries, drove Hungary into closer collaboration with Serbia, whose EU accession efforts it supported (Vörös & Tarrósy 2022).

We cannot, however, ignore the prominence of European structures. As a member of the EU, Hungary is not able to make itself independent of the Union’s foreign policy, and the EU is not capable of independent foreign policy action, and, if anything, the conflict in Ukraine has shown that the EU remains dependent on the United States. ‘The war erupted just as the EU was beginning to emerge from the economic crisis following the outbreak of the novel coronavirus and was about to start growing again. One might say that the timing of the war is unfortunate, but in fact wars always come at the wrong time. At the same time, the fact that Europe’s response to the invasion of Ukraine has been so doctrinaire, often against its own economic interests, does not suggest that the EU leadership is capable of assessing what Europe’s interests really are in the new world order’ (Ugrósdy 2024: 201). What is needed, therefore, is an autonomous, strategically independent Europe, which is well understood by Hungarian foreign policy. However, with its constant vetoes, Hungary is one of the impediments to the potential creation of this unity – in order to achieve the domestic policy goals already mentioned.

As we have already stated, ‘rebuilding this credibility should be the ultimate goal of the government, therefore, the discourse should not be about offended reactions and confrontation but about trade, business and economic interests; not about political party goals but country priorities’ (Tarrósy & Vörös 2020: 132) – and within this context, BRICS can remain a significant and meaningful option to fully benefit from the changes of the world order.

BRICS and the changing world order

Overview of the BRICS-dynamics

The BRIC acronym was coined by Goldman Sachs analyst Jim O’Neill in 2001 to highlight Brazil, Russia, India and China as emerging economies that were poised to surpass the G7 in growth. O’Neill argued for restructuring global policy frameworks like the G7 to better represent these growing markets, proposing a shift to a ‘G9’ that would include BRIC nations along with a unified EU to represent European interests (O’Neill 2011). While the G7 persisted without these states, O’Neill’s analysis had a significant impact, prompting the BRIC countries to begin organising joint meetings. By 2009, they institutionalised their collaboration in Yekaterinburg, Russia, and with South Africa’s addition in 2010, the coalition became BRICS.

Since then, BRICS has increased its influence through initiatives like the New Development Bank, formed to support members’ financial interests alongside organisations like the IMF and World Bank. BRICS countries now frequently coordinate on political and economic issues, seeking to consolidate their positions in international forums, as evidenced by their shared approach to UN Security Council votes (Feledy 2013). According to Haibin (2013), the BRICS economies, with their expanding size and diplomatic activity, are steadily gaining a larger role in international decision-making, making BRICS an attractive coalition for other emerging powers interested in balancing Western-dominated global institutions. While there is no official list of the states that have applied for BRICS membership, they are presumably among the emerging powers.

New BRICS members/aspirants

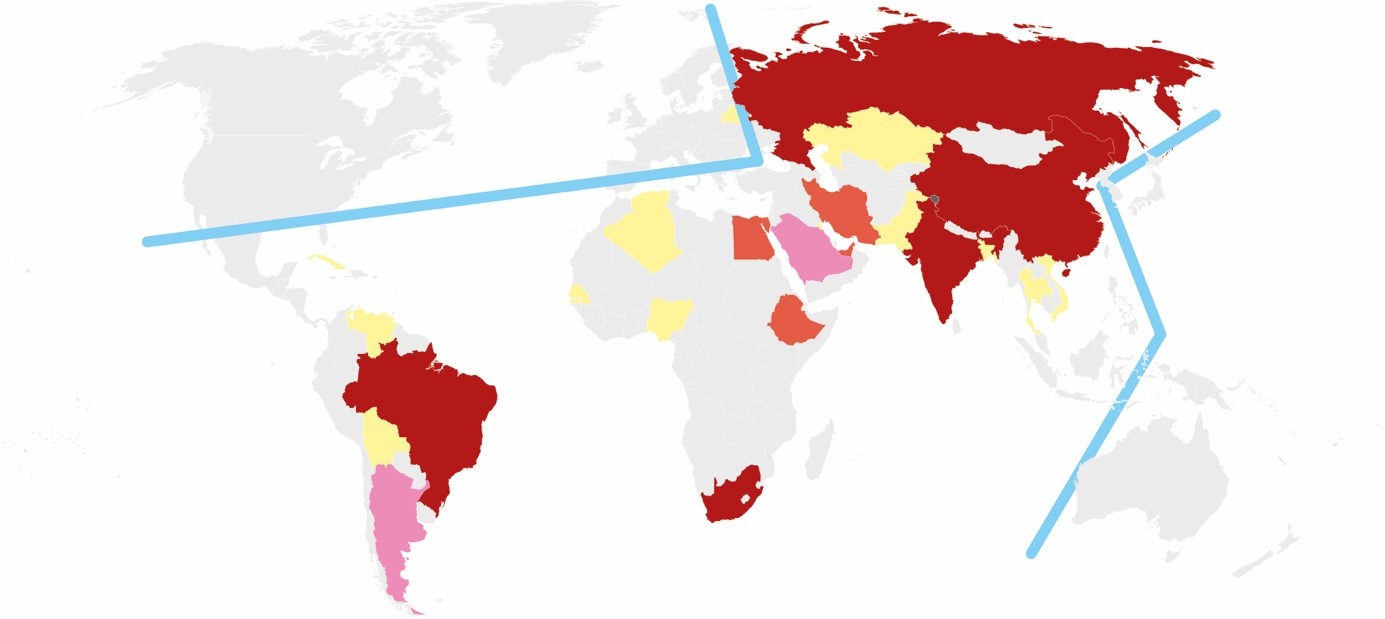

Considering the bloc’s economic benefits, burgeoning global influence and potential to shape the future of global finance, more and more nations have become eager to join BRICS. As of 2023, more than twenty countries, including Indonesia, Algeria and Nigeria, have formally approached BRICS countries to become full members (BRICS Portal 2023). Out of this growing number of interested countries, Iran, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Ethiopia, Egypt and Argentina were formally invited to join the bloc and reinforce its ranks following the 15th BRICS summit in Johannesburg in August 2023. This marked the bloc’s second expansion in more than a decade, a move zealously relaunched and urged by China during its BRICS presidency in 2022. This enlargement move was hailed as the most important development in the previous decade of BRICS history (Lissovolik 2024: 2). As Figure 1 shows, the grouping arguably aims to be a platform for empowering the Global South and giving greater prominence to its perspectives in global discussions (European Parliament Research Service 2024: 3). In this vein, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa posited that, through its new expansion, the BRICS grouping has embarked on a new chapter in its efforts to build a world that is fair [. . .] just [. . .] inclusive and prosperous (France24 2023).

Figure 1: BRICS in the world: Global South and Global North positions unaltered?

Legend: Red: BRICS (Original 4+1), Orange: New members from 2024, Pink: Countries approved for accession but which decided not to join, Yellow: Applicants according to various reports.

Source: Authors

Starting on 1 January 2024, the new cohort of countries became official members of the bloc except for Argentina and Saudi Arabia. Following the election of far-right President Javier Milei, Argentina withdrew from BRICS days before its planned entry to the bloc. In a similar vein, Saudi Arabia’s membership has not yet been made official, as more internal deliberations have been conducted concerning this polemical move. The membership of one of the world’s leading oil exporters and one of the Gulf´s biggest political and financial heavyweights is expected to give the bloc added heft (Fassihi et al. 2023). The region’s historical ties with the US, along with the changing geopolitical scene following the war in Gaza, are slowing down the ongoing negotiations between Saudi Arabia, Israel and the US.

Iran’s involvement in the BRICS expansion initiative has proven to be a significant diplomatic win, considering its long isolation due to its nuclear advances and support for Russia’s war against Ukraine. Though battered by Western sanctions, Tehran is still an important regional power and one of OPEC’s largest oil producers. In fact, it holds the world’s second largest gas reserves and a quarter of the oil reserves in the Middle East (Fassihi et al. 2023). Moreover, the United Arab Emirates’ decision to join the alliance is expected to further strengthen its economic ties with China and India, its two largest trading partners, and increase its role in the Middle East. The strong ties between the UAE and the US, mainly in the security sector, did not stop the country from adopting a pragmatic foreign policy that works on reinforcing trade and partnerships with both China and Russia. The presence of Saudi Arabia and the UAE together with Iran in the same bloc would not have been possible was it not for the Saudi-Iran détente brokered by China in March 2023.

Unlike Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, Egypt is not one of the world’s largest energy suppliers but rather one of the top recipients of American aid (Axelrod 2011: 3). Egypt joined the BRICS in a bid to bolster its economic relationships with prominent developing nations, most notably China and India, which are Egypt’s top two trading partners. Considering its ailing economy, Egypt suffers from various troubles such as inflation, dollar shortage and rising debt. Thus, it perceives the BRICS membership as an invaluable opportunity to ease its economic pressures via attracting more investments from member countries, trading in its local currency and improving its access to strategic commodities like wheat. The African presence in the bloc has been further boosted with the new membership of Ethiopia, which is the second most populous country on the continent (Le Monde 2023). Besides its prominent human capital and key role in founding the African Union, Ethiopia is one of the world’s fastest growing economies with a 7.2 percent growth during the previous fiscal year (2022–2023) (World Bank 2023: 2). Following the Tigray civil war of 2020–22, the US cut trade privileges and suspended food aid from the country (Fassihi et al. 2023). Thus, joining the BRICS seems to have been an opportunity to move further from the American orbit via securing alternative economic partnerships and attracting new investments.

Hungary’s relations with the core BRICS members

Hungary’s relations with the BRICS states, therefore, fit into the foreign policy concept of building relations with new potential poles – power centres of gravity – in a changing world, and in this respect treats the members of the organisation as middle powers – emerging economies with this potential. Hungarian foreign policy, pragmatic in its rhetoric, is focused solely on building political and economic relations with these states, looking ahead to the future and aligning with the perceived powers of the emerging world order. In this sense, Hungary views BRICS as a strategic partner and a promising platform for fostering economic collaboration and diplomatic partnerships outside of the Euro-Atlantic sphere. Acknowledging that ‘we are now living in a multipolar world order’ and that ‘Asia will be the dominant center of the world’, PM Orbán sees the BRICS as a pathway to diversify Hungary’s foreign alliances and reduce its over-dependence on the West (BRICS News 2024; Hungarian Conservative 2024). By fostering relations with BRICS nations, Hungary is positioning itself as a ‘bridge’ that connects East and West, aiming not only for collaboration but also for substantial economic and political gains from both blocs (Hungarian Institute of Foreign Affairs 2024) . In a world order marked by shifting power dynamics and the growing voices of the Global South, Hungary’s alignment with the BRICS can be considered as a sign of its flexible diplomacy and adaptive pragmatism. Through this dynamic pragmatism, Hungary seeks to bolster its international autonomy and build partnerships that advance its strategic goals within an increasingly multipolar global order.

1. Brazil

In the context of increasingly diversifying Hungarian foreign policy, one notable example is Hungary’s growing relationship with Brazil. This relationship has developed within the broader context of Hungary’s Global Opening policy, in line with its central aims to expand economic, political and cultural ties beyond the traditional trans-Atlantic focus on Europe and North America.

Historically, Hungary and Brazil have had limited interactions, largely due to geographical distance and differing regional priorities. However, the end of the Cold War and subsequent globalisation trends have provided new opportunities for these two nations to explore bilateral cooperation. The establishment of diplomatic relations in March 1961 laid the foundation for future engagements, but it is only in recent decades that substantial progress has been made.

One important dimension of bilateral ties that evolved over time from the turn of the 20th century up until the 1956 Hungarian Revolution is the presence of Hungarians and Hungarian descendants in Brazil. Today, this number is estimated to be at least 100,000. According to Csrepka:

the Hungarian community in the city and region of São Paulo today numbers more than 10,000, and there is also a significant number of Hungarians in other cities: Rio de Janeiro, Curitiba, and Porto Alegre. Therefore, it is not easy to estimate the number of descendants, which could vary between 150 and 300 thousand. (Csrepka 2022: 129)

This diaspora community is seen as a crucial thread between the two countries, also with regard to fostering business-related cooperation.

Amongst the different policy layers, economic engagement forms a cornerstone of Hungary-Brazil relations. Brazil, as the largest economy in Latin America, presents significant opportunities for Hungarian businesses. Trade between the two countries has been steadily increasing, with Hungarian exports to Brazil including machinery, pharmaceuticals and agricultural products. Conversely, Brazil exports mainly raw materials and food products to Hungary. In addition to this dimension and beyond a continuous political dialogue, certain issues such as sustainable development, international security and migration, as well as education and technology exchanges were placed high on the bilateral agenda – particularly during Jair Bolsonaro’s presidential term (2019–2023). In October 2019, Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó said that Hungary wanted to ‘develop “the closest ever” ties with Brazil, since the two countries’ leaders share[d] very similar approaches to global politics’ (About Hungary blog 2019), referring to the fine understanding between President Bolsonaro and Prime Minister Orbán. This ‘closest’ tie was reaffirmed in February 2024 when Bolsonaro spent two nights in the Hungarian embassy in Brasília, ‘presumably to hide from Brazilian authorities that were investigating his alleged coup attempt’ (Leali 2024).

In terms of soft power and cultural diplomacy, the Hungarian government has offered Brazilian students opportunities to pursue full-degree bachelor’s and master’s studies in fields such as agriculture, engineering, natural sciences, sports, social sciences and the arts within the framework of the Stipendium Hungaricum scholarship scheme.[1] Brazil has an annual quota of 250 students provided by the Hungarian government on a bilateral basis. The scholarship is financed from taxpayers’ contributions to the national budget and it does not contain EU elements. Moreover, other cultural diplomacy initiatives include Hungarian cultural festivals and exhibitions in Brazil, with the intention of raising awareness about Hungarian heritage and culture. These activities complement the broader strategy of enhancing Hungary’s soft power on the international stage. Complementing these efforts, Brazil sent Brazilian students to Hungary (and many other parts of the globe) with its own governmental scheme: between 2011 and 2015, the Science without Borders scholarship programme allowed 100,000 scientific exchanges overseas in areas identified as priorities for the country’s development – mostly in STEM fields (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) (Estudo No Exterior n.d.).

2. Russia

Hungary’s relationship with Russia is shaped not only by its socialist past, but also by its energy dependence, which has become a key issue since the Russo-Ukrainian War. Until the outbreak of the conflict in 2022, Hungary imported 85% of its natural gas and over 60% of its oil from Russia (ATV 2022). Despite Hungary’s sometimes hesitant vote for EU sanctions, the Russian share of imports remained significant – mainly due to the fact that Hungary, as a land-locked country, was already highly dependent on Russian energy. In the event of a full cut of Russian imports, it is unequivocally ‘the countries of Central and Eastern Europe that would face the highest prices due to internal bottlenecks preventing LNG from reaching these markets from West to East’ (Kotek et al. 2022: 240). The Hungarian government’s position demanding slower action and sanctions is a logical request, and this has also been accepted by the community which allows for further imports, although Ukraine is likely to stop gas transit at the end of 2024, posing new questions for the players in the region.

Hungary is often criticised for these very actions, and while the economic interest is understandable, in many cases Budapest has indeed adopted a softer policy towards Moscow, and the 2023 Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) summit between Orbán and Putin did not help the acceptance of the Hungarian side’s position within the EU. The Hungarian government explains its cooperation by multilateral interests and a changing world order, but, as we have already discussed in the section on pragmatic foreign policy, it seems implausible that Hungary aims to become a truly pragmatic actor while drifting further and further away from Western values. Its pro-Russian stance has in fact made the country a lonely actor within the EU, even at the cost of pushing the Visegrad Cooperation (V4, including Czechia, Slovakia and Poland together with Hungary) into crisis. The previously important scheme of four CEE countries helped Orbán to set the goal of becoming the new engines of Europe – but because of the Hungarian interpretation of the war, the V4 is hardly a club of countries with similar interests and understandings within the EU anymore. Moreover, the continuous vetoes of Hungary regarding further sanctions on Russia creates an even more hostile environment for Budapest within the EU, further questioning the pragmatic approach.

Regarding Russia, there are two more issues worth mentioning: one is the nuclear power plant expansion at the town of Paks, about 60 miles southwards along the river Danube, which has been dragging on for years and it is rather questionable if the Russians will finally build it – although both sides are waiting to admit this. The other is the Hungarian army mission in Chad, which will take place outside the EU, NATO and the UN in a region where Russia’s interests are growing and where anti-Western sentiment is so palpable: it is no coincidence that some fear (RLI 2024) that the Hungarian military presence could serve Russian interests.

3. India

Since the establishment of bilateral diplomatic ties in 1948, Hungary’s relations with India have been described as friendly, multifaceted and substantive (Embassy of India, Hungary and Bosnia & Herzegovina 2023). Besides the recently growing number of high-level visits from both countries, India and Hungary signed a new series of bilateral treaties and agreements in various fields such as investment, education and water management. In 2015, the total bilateral trade between India and Hungary was USD 578.3 million. This figure hit a new record in 2022 as it reached USD 1.2 billion with USD 790.7 million Hungarian imports and USD 491million Hungarian exports (Embassy of India, Hungary and Bosnia & Herzegovina 2023). Major Hungarian exports to India include mechanical appliances, electrical machinery and medical and surgical instruments. India was the largest greenfield investor in Hungary in 2014 and the number of Indian investments has been growing ever since as many companies expanded their bases in the country. The Indian presence in Hungary includes major companies such as Apollo Tyres, Sun Pharmaceuticals and Tata Consultancy Services. As of 2020, the total investment value of Apollo Tyres reached EUR 700 million, with the company employing over 800 workers (Embassy of India, Hungary and Bosnia & Herzegovina 2023). In total, Indian companies in Hungary provide employment to over 10,000 people. Education is another field of growing cooperation between the two nations as 44 candidates from Hungary availed the Indian Technical & Economic Cooperation (ITEC) programme between 2007 and 2023. According to Tempus Public Foundation, the number of Indian holders of the Stipendium Hungaricum scholarship, offered by the Hungarian government, rose from 60 students in 2015 to 420 students in the 2023–2024 academic year (Tempus Public Foundation 2023). India has an annual quota of 200 student placements. In a similar vein, cultural links between India and Hungary have been steadily evolving since the opening of the Indian Cultural Centre in Budapest in 2010. The Amrita Sher-Gil Cultural Centre has been organising various cultural activities like yoga, dance and Hindi classes. In 2016, the Ganga-Danube Cultural Festival was launched, featuring artists, performers and dancers from India. Other cultural initiatives and celebrations reinforcing the cultural ties between the two countries entail the International Day of Yoga, the Indian Film Festival and Mahatma Ghandi’s birth anniversary (Szenkovics 2019: 13). Individual institutional activities, such as the International Seasons intercultural events series of the University of Pécs,[2] further enhanced bilateral linkages.

4. China

Hungary’s relations with China are widely depicted as multifaceted and prosperous mainly after Orban’s 2010 ‘Eastern Opening’ Policy. The Fidesz leader’s desire to develop economic relations with the non-Western world has been at the core of deepening the Sino-Hungarian ties (Végh 2015: 47). Following a meeting in Budapest in 2011, leaders of China and 16 countries of Central and Eastern Europe announced the China-CEE cooperation mechanism (Embassy of Hungary Beijing 2023). The 16+1 initiative[3], now known as the 14+1, was launched with the aim of bolstering and strengthening relations between Beijing and these CEE countries through broadening investments and business prospects. Supporting Chinese initiatives in Europe, Hungary was the first European country to join the Belt and Road Initiative through projects like the Central European Trade and Logistics Cooperation Zone (CECZ) and the Budapest–Belgrade (BuBe) railway line. ‘Along the new routes of this emerging connectivity network via the Silk Road Economic Belt and the Maritime Silk Road, Central and Eastern European countries clearly present a strategic region for China’ (Tarrósy & Vörös 2019: 259).

China is, indeed, one of Hungary’s major trading partners globally and its most important partner in Asia (Szunomár & Peragovics 2019: 3). Bilateral trade between China and Hungary hit USD 14.52 billion in 2023, an increase of 73% compared to 2013 (Asian Financial Cooperation Association 2024). Top exports from Hungary to China were navigation equipment, electrical transformers, and parts and accessories of motor vehicles (Observatory of Economic Complexity 2024). Interestingly, Beijing has been Hungary’s leading foreign investor since 2020 as China’s direct investments reached EUR 7.6 billion in 2023 (Asian Financial Cooperation Association 2024). Recently, BYD, the Chinese electric vehicles giant, picked the Hungarian city of Szeged as the site of its first car factory in Europe. In the field of education, the first Confucius Institute (CI) in Hungary was established at Eötvös Loránd University in 2006. Following its inauguration, other Confucius Institutes were founded in Szeged, Miskolc and Pécs. The one in Pécs is the only traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)-focused CI in Europe. In the 2023–2024 academic year, about 345 Chinese students held Stipendium Hungarian scholarships (Tempus Public Foundation 2023). The inauguration of Hungarian centres in Beijing and Tangshan and the planned construction of Fudan University in Budapest – as the first overseas campus of the Shanghai-based institution – are but examples of the burgeoning educational cooperation between the two nations. These are coupled with several cultural events, which can grab the hearts and minds of the populations of both countries. Among the events organised by the Beijing Hungarian Cultural Institute, for instance, we find several education-related ones, such as the Kodály Point programme, which was started in October 2015, offering ‘music classes in small groups for children between the age 3-12, for adults, and also choir classes for poor children from the neighbourhood’ (Tarrósy & Vörös 2019: 267; Embassy of Hungary 2019).

5. South Africa

According to the official website of the Hungarian Embassy in Pretoria, former Ambassador Attila Horváth highlighted that the Republic of South Africa ‘occupies a prominent place in [Hungary’s] network of relations with sub-Saharan Africa’.[4] In a 2014 interview with the then South African ambassador to Hungary for the US-Africa portal AFKInsider, Ambassador Johann Marx explained, ‘Hungary and South Africa share a common experience in that both countries emerged in the early 1990s from relative global isolation, due to the so-called “Iron Curtain” imposed on Hungary by Soviet occupation following World War II, while during the same period, South Africa experienced the ideological “Iron Curtain” of apartheid.’ Therefore, it is not surprising that both Hungary and South Africa were ‘obliged in the years that followed to focus on their economic re-integration in their respective regions’, according to Ambassador Marx (Tarrósy 2014).

In terms of investments, large South African companies were active in Hungary in the 1990s – notable examples include SAB, Mondi, Group 5, Intertoll, Ster-Kinekor and Steinhoff International. Moving into the new millennium, small and medium-sized companies, such as Naspers and CNS, began expanding their business activities in both directions. In 2013–14, South African investments in Hungary were estimated at about USD 250 million. Trade figures reveal that while in 2014 the total volume stood at USD 283 million (with Hungary enjoying an 88% trade surplus), by 2020 the total had decreased to USD 194 million, still favouring Hungary substantially (with a surplus of USD 136 million, or 82% of the total), but with a minor 6% increase on the South African side. In recent years, real estate has emerged as the primary sector for South African capital, with the South African property developer NEPI Rockcastle being the largest real estate investor in Central and Eastern Europe (Tarrósy 2022).

From a political perspective, both Hungary and South Africa consider it important to develop bilateral linkages. Reflecting this, on 13 May 2013, they established the South Africa-Hungary Joint Economic Commission to develop and diversify relations. In a November 2015 meeting, the two governments outlined areas of cooperation: education and training (including student exchange for skills development), manufacturing (joint ventures on car components and bus manufacturing), pharmaceuticals, water management and water technology, agriculture, tourism and banking.

As underscored several times, education and research are pivotal in reshaping Hungary’s presence in Africa, potentially forming the basis for long-term cooperation, and the Stipendium Hungaricum public scholarship programme is a key component of Hungary’s foreign policy and evolving Africa policy. With an annual quota of 100 places for South African students, those who graduate from Hungarian universities often become advocates for bilateral collaboration. In addition, a new government scholarship targets the descendants of former emigrants, focusing on diasporic communities. The Hungarian Diaspora Scholarship is available for members of the Hungarian diaspora living outside of the European Union, Serbia and the Zakarpattia Oblast of Ukraine. Local diaspora organisations issue letters of recommendation, facilitating the process.

For South Africa, the Hungarian Alliance of South Africa is involved in this process. The alliance, with roots dating back to 1932 and re-established in 1953, has continuously worked to preserve Hungarian language, values and culture in South Africa. Its mission includes nurturing these cultural aspects, commemorating important events in Hungarian history, and fostering a strong Hungarian community in South Africa. The alliance is the official partner of the Hungarian government, which engages with its diasporic communities through the Diaspora Council. This council forms part of a broader governmental effort to support diaspora communities. As Prime Minister Orbán emphasised in his 2019 speech to the Diaspora Council, the aim is to ‘join the blood circulation of the Hungarian nation’ (Tarrósy 2022).

Conclusion

In this paper, our hypothesis posited that while BRICS members and countries aspiring for membership demonstrate an increasing preference for a multipolar global order, the prevailing dominant power appears inclined towards re-establishing a bipolar scenario. Amidst these evolving dynamics, it has been observed that Hungary, since the early 2010s, has been advancing its ‘Global Opening’ foreign policy initiative, shifting its previously pragmatic agenda towards prominent new doctrines concerning the emerging Global South, particularly focusing on the East. In any case, it seems that the Hungarian government’s global assessment of the changing world order and the role of the BRICS in this transformation is in line with global political realities. While the relations with emerging countries that have been developed on the basis of this recognition have corresponded to this perceived future, the idea of multipolarity has not been maintained in relations with the Western, Euro-Atlantic partners: the pragmatic approach has been disappearing. Pragmatic considerations of the broader macro-region, along with shared historical ties, intercultural connections and economic interests with neighbouring countries, have driven Hungary into closer collaboration with Serbia, for example, and have positioned the country as a key actor in the macro region of the Western Balkans. However, it can be concluded that by 2024, Hungary had further isolated itself from its Western partners, pursuing an increasingly anti-Western foreign policy. This discernible shift suggests that Hungary’s foreign policy directions are growingly influenced by ideological preferences, especially those that align with a multipolar vision of the world, as outlined in BRICS-oriented frameworks. Yet, as Hungary leans further toward anti-Western policies, it risks severing ties that could otherwise support its strategic and economic interests.

Pragmatism, as we have emphasised, would facilitate relations with emerging actors while maintaining Western partnerships, aligning more effectively with the multipolar worldview defined and envisioned by the Hungarian government. Therefore, the fading away of pragmatism in Hungarian foreign policy, and in particular the changing pattern and evolving nature, requires more nuanced critical attention and research.

Working with our research questions allowed us to come to the conclusion that the power dynamics of the changing international arena is multifaceted, which requests a critical geopolitical approach to shed light on its complexities, amongst which we find the importance of soft power and cultural diplomacy both as useful approaches and tools. The analysis of Hungary-BRICS relations enriches our understanding of Hungary’s foreign policy shifts, highlighting its evolving priorities, strategic ambitions and adaptive responses to the changing international landscape. Through this lens, the paper reveals that BRICS states as much as Hungary, with its aspirations to forge closer ties with BRICS, use soft power to widen and strengthen their engagements. State scholarships have been placed high on the political agendas and can prove Nye’s predicament about ‘smart power’ (Nye 2004: 32), which in fact is about how to combine hard and soft power to enhance the positions of the given actor in the international system. Offering such opportunities to foreign publics can contribute to ‘winning the hearts and minds’ and to building support constituencies for the Hungarian interest abroad – former graduates undoubtedly cultivate ties with their alma maters and host countries and can, therefore, function as real actors of furthering bilateral relations. Hungary’s relations with members of the BRICS have dynamically developed and showed the evolving context of rather this ‘smart power’ approach than the formerly evident pragmatism the country strived for. As a next step, the deeper investigation between smart power and pragmatism in international relations may contribute to a better understanding of the changing world order, which cannot neglect the growing voices of the countries of the Global South.

***

Funding

No funding information.

István Tarrósy is Full Professor of Political Science at the Department of Political Science and International Studies, University of Pécs (UP), Hungary, and Visiting Professor at Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland. He also directs the Hungarian Africa Research Center and is head of the Doctoral Program in International Politics at UP. He was a Fulbright Visiting Scholar at the Center for African Studies (CAS) of the University of Florida in 2013-14. He is member of the China–Africa Working Group at CAS and Courtesy Affiliate Professor at the Center for Arts, Migration and Entrepreneurship (CAME). He is co-convenor of the Collaborative Research Group ‘Africa in the World’ of AEGIS African Studies in Europe. His research interests include Afro-Asian relations, China–Africa dynamics, the international relations and geopolitics of Sub-Saharan Africa and global African migrations, Hungarian and Central European foreign policies towards the Global South, and the changing world order. He is Editor-in-Chief of the Hungarian Journal of African Studies (Afrika Tanulmanyok).

Hajer Trabelsi is MA in International Relations and PhD candidate at the Doctoral Programme in International Politics, Department of Political Science and International Studies at the University of Pécs, Hungary. Her research interests include geopolitics, Sino-American tensions and Chinese Foreign Policy. Hajer is currently working on her dissertation touching upon the geopolitical implications of the COVID-19 pandemic through the lenses of Sino-American tensions.

Zoltán Vörös is a habilitated Doctor of Political Science, Associate Professor and Academic supervisor of the International Relations BA Program at the Department of Political Science and International Studies at the University of Pécs. He has been a researcher and a project manager for several European Integration Fund and Refugee, Migration and Integration Fund projects, as well as in charge of University projects and Chair of a University Committee in Internationalisation. He is an editor of Afrika Tanulmányok/Hungarian Journal of African Studies and Pólusok/Polarities academic journals. He was a guest lecturer at Metropolitan State University of Denver between 2017 and 2022, and is a regular visiting lecturer at higher education institutions, and was the organiser of the DRC Summer School from 2008 to 2023, one of the most relevant summer schools of the CEE region. His research interests cover international relations and security studies, focusing on China's foreign and security policy and the global implications of its economic rise.

References

About Hungary (2019): FM: Hungary wants to build "closest ever ties" with Brazil. About Hungary, 10 October, <accessed online: https://abouthungary.hu/news-in-brief/fm-hungary-wants-to-build-closest-ever-ties-with-brazil>.

About Hungary (2023): Youth counselling center built with Hungarian support inaugurated in Ethiopia. About Hungary, 19 April, <accessed online: https://abouthungary.hu/news-in-brief/youth-counselling-center-built-with-hungarian-support-inaugurated-in-ethiopia>.

AFCA (2024): CEIS releases China-Hungary investment and cooperation report in Budapest. AFCA, 7 May, <accessed online: https://www.afcaasia.com/Portal.do?method=detailView&returnChannelID=23&contentID=1788>.

ATV (2022): Az orosz olajimport betiltásán dolgozik az EU, a magyar kormány ellenáll [The EU is working to ban Russian oil imports, but the Hungarian government is resisting]. atv.hu, 16 April, <accessed online: https://www.atv.hu/belfold/20220416/az-orosz-olajimport-betiltasan-dolgozik-az-eu-a-magyar-kormany-ellenall>.

Axelrod, M. C. (2011): Aid as Leverage? Understanding the U.S.-Egypt Military Relationship (Master's thesis). The Lauder Institute, University of Pennsylvania, <accessed online: https://lauder.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Axelrod.pdf>.

BRICS News [@ BRICSinfo] (2024, May 11): Hungary Prime Minister Viktor Orbán speech to Chinese President Xi Jinping. [Post]. X, <accessed online: https://x.com/BRICSinfo/status/1789144627729101076>.

BRICS Portal (2024): Why 40+ Countries Want to Join BRICS. BRICS Portal, 24 August, <accessed online: https://infobrics.org/post/39185/>.

Buzan, B. (2013): Polarity. In: Williams, P. D. (ed.) Security Studies – An Introduction. London: Routledge, 155–169.

Buzna, V., Goreczky, P., Kránitz, P., Salát, G. & Seremet, S. (2024): 5 Facts - A Growing BRICS and the Changing International System. Hungarian Institute of Foreign Affairs, 24 October, <accessed online: https://hiia.hu/en/5-facts-a-growing-brics-and-the-changing-international-system/>.

Császár, Zs., Tarrósy, I., Dobos, G., Varjas, J. & Alpek, L. (2023): Changing geopolitics of higher education: economic effects of inbound international student mobility to Hungary. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 47(2), 285–310.

Cochran, M. (2012): Pragmatism and International Relations. A Story of Closure and Opening. European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy, 2(4), 1–22.

Csrepka, M. B. (2022): Hungarians and their dual identity in São Paulo. Alkalmazott Nyelvtudomány, 22(2), 126–145.

Embassy of Hungary Beijing (2023): Political and Diplomatic Relations, <accessed online: https://peking.mfa.gov.hu/eng/page/politikai-kapcsolatok>.

Embassy of India (2023): India-Hungary Bilateral Relations, <accessed online: https://www.eoibudapest.gov.in/page/india-hungary-relations/>.

Estudo No Exterior (n.d): Science without Borders, <accessed online: https://estudonoexterior.com/science-without-borders>.

European Parliament (2024): Expansion of BRICS: A quest for greater global influence? <accessed online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2024/760368/EPRS_BRI(2024)760368_EN.pdf>.

Fassihi, F., Yee, V., Alcoba, N. & Walsh, D. (2023): What to Know About the 6 Nations Invited to Join BRICS. The New York Times, 28 August, <accessed online: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/23/world/asia/brics-nations-new-members-expansion.html>.

Feledy, B. (2013): Birodalmi bukfencre készülünk. [We are preparing for an imperial tumble]. Kitekintő, 16 March, <accessed online: http://kitekinto.hu/velemeny/2013/03/26/birodalmi_bukfencre_keszulunk/#.Urh3P_TuJic>.

France24 (2023): BRICS invites six new members to join bloc in bid to champion ‘Global South’. France24, 24 August, <accessed online: https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20230824-brics-set-to-invite-six-new-members-to-join-bloc-in-bid-to-champion-global-south>.

Freddy, H. J. & Thomas, C. J. (2023): Status Competition: The BRICS’ Quest for Influence in Global Governance. China Report, 59(4), 388–401.

Freedman, L. (1999): The New Great Power Politics. In: Arbatov, A. G., Kaiser, K. & Legvold, R. (eds.): Russia and the West. The 21st Century Security Environment. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 21–43.

Haibin, N. (2013): BRICS in Global Governance A Progressive and Cooperative Force? Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Perspective, <accessed online: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/iez/global/10227.pdf>.

Hungarian Ministry of Defence (2024): Military and defence industrial cooperation between Hungary and the United Arab Emirates, 22 April, <accessed online: https://defence.hu/news/military-and-defence-industrial-cooperation-between-hungary-and-the-united-arab-emirates.html>.

Huntington, S. P. (1999): The lonely superpower. Foreign Affairs, 78(2), 35–49.

Kacziba, P. (2020): Political Sources of Hungarian Soft Power. Politics in Central Europe, 16(1S), 81–111.

Kapoor, N. (2023): Sino-Russian partnership in the ‘Asian Supercomplex’: choices and challenges for India. Journal of Eurasian Studies, 15(2), 239–252.

Kiss, B. & Zahorán, Cs. (2007): Hungarian Domestic Policy in Foreign Policy. International Issues and Slovak Foreign Policy Affairs, 16(2), 46–64.

Kotek, P., Selei, A. & Takácsné Tóth, B. (2022): Oroszország gázpiaci erejének vizsgálata Európában a közös EU-stratégia tükrében. [Examining Russia's gas market power in Europe in the light of a common EU strategy]. Verseny és szabályozás, 2022(1), 224–242.

Kovács, E. (2020): Diaspora Policies, Consular Services and Social Protection for Hungarian Citizens Abroad. In: Lafleur, J.-M. & Vintila, D. (eds.): Migration and Social Protection in Europe and Beyond (Volume 2), IMISCOE Research Series, Cham: Springer, 245–258.

Leali, G. (2024): Hungary hid Brazil’s Bolsonaro in embassy while police investigated alleged coup attempt. Politico, March 25, <accessed online: https://www.politico.eu/article/hungary-hid-bolsonaro-from-brazilian-police-amid-coup-investigation/>.

Lechner, Z. (2021): Orosz külpolitikai diskurzusok a posztszovjet időszakban [Russian Foreign Policy Discourses in the Post-Soviet Period ]. Valóság, 64(7), 16–25.

Le Monde (2024): Iran, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Argentina, Egypt and Ethiopia set to join the BRICS. Le Monde, 24 August, <accessed online: https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2023/08/24/iran-saudi-arabia-egypt-uae-argentina-egypt-and-ethiopia-set-to-join-the-brics_6106146_4.html>.

Lissovolik, Y. (2024): BRICS expansion: new geographies and spheres of cooperation. Editorial for special Issue. BRICS Journal of Economics, 5(1), 1–12.

Marlok, A. Z. (2024): Bridge among Cultures and Worlds: István Zimonyi’s Work Related to the Arab World in the Light of Egyptian–Hungarian Cultural Relations. Journal of Central and Eastern European African Studies, 3(2), 177–200.

McCarthy, S. (2023): China has a sweeping vision to reshape the world – and countries are listening. CNN, 10 November, <accessed online: https://edition.cnn.com/2023/11/09/china/china-xi-jinping-world-order-intl-hnk/index.html>.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) (2011): Hungary’s Foreign Policy after the Hungarian Presidency of the Council of European Union. Budapest, <https://brexit.kormany.hu/admin/download/f/1b/30000/foreign_policy_20111219.pdf>.

Motin, D. (2024): Two’s Company, Three’s a Crowd: Tripolarity and War. Central European Journal of International and Security Studies, 18(2), 5–33.

Nye, J. S. (2004): Soft Power. The Means to Success in World Politics. New York: Public Affairs.

O’Neill, J. (2001): Building Better Global Economic BRICs. Goldman Sachs, Global Economics Paper, No. 66, <accessed online: https://www.goldmansachs.com/intelligence/archive/archive-pdfs/build-better-brics.pdf>.

Ó Tuathail, G. (1996): Critical Geopolitics. The Politics of Writing Global Space. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Pant, H. V. (2023): From BRICS to BRICS Plus: Old Partners and New Stakeholders. Observer Research Foundation. (No. 214) https://www.orfonline.org/public/uploads/posts/pdf/20231229212147.pdf

Puzyniak, A. (2018): Hungarian foreign policy after 2010 – selected problems. Facta Simonidis, 11(1), 231–242.

Ralston, S. J. (2011): Pragmatism in International Relations Theory and Research. Eidos: Revista de Filosofía de la Universidad Del Norte, 14, 72–105.

RLI (2024): Hungary is setting closer cooperation with Russia in Chad, 14 May, <accessed online: https://lansinginstitute.org/2024/05/14/hungary-is-setting-closer-cooperation-with-russia/>.

Scheffer, J. (2024): Viktor Orbán at Tusványos: ‘Donald Trump is the last chance for America to maintain its global supremacy’. Hungarian Conservative, 27 July, <accessed online: https://www.hungarianconservative.com/articles/current/tusvanyos_viktor-orban_speech_donald-trump_global-supremacy_brussels_war_peace-mission_new-world-order/>.

South African Government (2013): Fifth BRICS Summit – general background, <accessed online: https://www.gov.za/events/fifth-brics-summit-general-background>.

Sz. Bíró, Z. (2014): Oroszország és a posztszovjet térség biztonságpolitikája [Security Policy of Russia and the Post-Soviet Space], 1991–2014 (II.). Nemzet és Biztonság, 2014/4, 37–55.

Szenkovics, D. (2019): Cultural Ties between Hungary and India. A Short Overview. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae European and Regional Studies, 16(1), 91–119.

Szunomár, Á. & Peragovics, T. (2019): Hungary. An Assessment of Chinese-Hungarian Economic Relations. In: Comparative Analysis of the Approach Towards China. Institute of World Economics, Centre for Economic and Regional Studies, Hungarian Academy of Sciences; Prague Security Studies Institute; Institute of Asian Studies (IAS); Belgrade Fund for Political Excellence (BFPE); Centre for International Relations. <accessed online: http://real.mtak.hu/id/eprint/100137>.

Tálas, P. (2021): A poszthegemoniális nemzetközi hatalmi rendről. [On the post-hegemonic international power order] In: Kajtár, G. & Sonnevend, P. (eds.): A nemzetközi jog, az uniós jog és a nemzetközi kapcsolatok szerepe a 21. században: tanulmányok Valki László tiszteletére. [The role of international law, EU law and international relations in the 21st century: studies in honour of László Valki] Budapest: ELTE Eötvös Kiadó, 841–854.

Tarrósy, I. (2014): South African Brands Find Market In Central Europe, AFKInsider, 21 July, <accessed online: https://moguldom.com/65423/south-africa-invests-central-europe/>.

Tarrósy, I. (2022): Hungarian Community in South Africa and New Opportunities for International Cooperation in the Post-Apartheid Era. In: Kachur, D., Szewczuk, S. & Rademeyer, C. (eds.): Socio-Economic Connections between Eastern Europeans in South Africa: Conference proceedings 2022. Cape Town: Sol-Plaatje University, 6–16.

Tarrósy, I. & Morenth, P. (2013): Global Opening for Hungary: A New Beginning for Hungarian African Policy? African Studies Quarterly, 14(1–2), 77–96.

Tarrósy, I & Vörös, Z. (2014): Hungary’s global opening to an interpolar world. Politeja, 28, 139–162.

Tarrósy, I. & Vörös, Z. (2019): Kínai–magyar együttműködés a felsőoktatásban és a kutatásban: Hetven év áttekintése a kétoldalú diplomáciai kapcsolatok fényében. [Sino-Hungarian cooperation in higher education and research: a review of seventy years of bilateral diplomatic relations]. In: Goreczky, P. (ed.): Magyarország és Kína: 70 éves kapcsolat a változó világban [Chinese-Hungarian Cooperation in Higher Education and Research: A Seventy-year Overview in Light of Bilateral Diplomatic Relations. In : Goreczky, P. (ed.): Hungary and China: 70 years of Relations in a Changing World ] Budapest: Külügyi és Külgazdasági Intézet, 196–213.

Tarrósy, I. & Vörös, Z. (2020): Hungary’s Pragmatic Foreign Policy in a Post-American World. Politics in Central Europe, 16(s1), 113–134.

Tempus Public Foundation (2023): Stipendium Hungaricum hallgatók statisztikai száma az állampolgárság országa szerint [Statistics of Stipendium Hungaricum Students by Country of Citizenship] , 2015–2023, <accessed online: https://tka.hu/palyazatok/7619/statisztikak>.

The Observatory of Economic Complexity (2024): China/Hungary, <accessed online: https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/chn/partner/hun>.

The Observatory of Economic Complexity (2022): Ethiopia/Hungary, <accessed online: https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/eth/partner/hun>.

The World Bank (2023): Ethiopia Country Program Evaluation, <accessed online: https://ieg.worldbankgroup.org/sites/default/files/Data/reports/ap_ethiopia_cpe.pdf#:~:text=2.4%20Ethiopia%20has%20been%20one,to%20US%24925%20in%20202>.

Trading Economics (2024): Hungary Exports to United Arab Emirates. Trading Economics, <accessed online: https://tradingeconomics.com/hungary/exports/united-arab-emirates>.

Tripathi, S. P. M. (2010): Relevance of International Organizations. The Indian Journal of Political Science, 71(4), 1243–1250, <accessed online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/42748951>.

Ugrósdy, M. (2024): Nyugaton a helyzet változatlan: Európa, az Európai Unió és a világrend átalakulása [The situation in the West remains unchanged: Europe, the European Union and the transformation of the world order] In: Vörös, Z. & Tarrósy, I. (eds.): Átalakuló világrend. Az unipoláris pillanat vége? [A changing world order. The end of the unipolar moment?] Budapest: Ludovika, 181–207.

United Arab Emirates Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2021): Cultural Cooperation, 7 June, <accessed online: https://www.mofa.gov.ae/en/Missions/Budapest/UAE-Relationships/Cultural-Cooperation>.

Végh, Zs. (2015): Hungary’s “Eastern Opening” policy toward Russia: ties that bind? International Issues & Slovak Foreign Policy Affairs, 24(1/2), 47–65.

Vörös, Z. (2022): Kínai geopolitika a 21. században: a globális világrend megkérdőjelezése? [Chinese geopolitics in the 21st century: challenging the global world order?] Eurázsia Szemle, 2(1), 8–28.

Vörös, Z. & Tarrósy, I. (2022): Hungarian Foreign Policy Agenda in Relation to Serbia and the Process of European Integration. In: Mileski, T. & Dimitrijević, D. (eds.): International Organizations: Serbia and Contemporary World, Vol. 1. Belgrade–Skopje: Institute of International Politics and Economics (IIPE), Ss. Cyril and Methodius University, Faculty of Philosophy, 532–546.

Vörös, Z. & Tarrósy, I. (2024): Az átalakuló világrend és a pólusok elmélete. [The changing world order and the theory of poles] In: Vörös, Z. & Tarrósy, I. (eds.): Átalakuló világrend. Az unipoláris pillanat vége? [A changing world order. The end of the unipolar moment?] Budapest: Ludovika, 11–35.

Waltz, K. N. (1979): Theory of International Politics. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

Xiaolin, M. (2023): BRICS reflects rising voice of Global South. China Daily, 13 September, <accessed online: https://epaper.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202309/13/WS6500dc2da31020d7c67bc926.html>.

[1] See <https://stipendiumhungaricum.hu/>.

[2] See <https://www.facebook.com/InternationalSeasonsPTE>.

[3] Greece officially joined the 16+1 initiative in 2019 and the initiative became known as the 17+1 initiative. However, Lithuania announced its exit from the initiative in 2021, and was later followed by Estonia and Latvia.