Abstract

The end of the Cold War saw a shift in power dynamics globally, changing the security dynamics of many regions globally including those in Africa. With the security void left by these great powers in Africa, regional hegemons have played significant roles in promoting regional peace and stability. Regional hegemons have greatly helped to sustain peace and stability in the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and Southern African Development Community (SADC), but this has not been the case in the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS). This paper seeks reasons why no hegemon (dominant state) exists in the ECCAS region. The study analyses the material resource capacities of regional members and argues that a multiplicity of regional groupings, internal political instability, economic challenges and the neo-colonial hand of France accounts for the absence of a hegemon in the region.

Keywords

Introduction

The global decline in interstate conflicts has brought many security analysts to the conclusion that the nature of global conflicts has changed since the Cold War ended.[i],[ii] The Central African region has in recent times been rocked by a series of clashes between armed groups and military forces. This has particularly been the case in the Congo and the Central African Republic since independence and more recently in Cameroon since 2016. The civil wars in these countries have come to have significant security implications for the sub-region and for other neighbouring countries. Located in a conflict-marred sub-region, Cameroon had for a long time been looked upon as an island of peace. A turn of events in 2016 totally changed this erstwhile legacy with the emergence of the Anglophone war for separation. The Central African Republic has also been marred with episodes of conflict since it gained independence in 1960.

A plethora of conflicts and separatist incidents have rocked many countries in the Central African region and has included countries like Angola, Chad, Congo and the DRC[iii]. While other sub-regions like ECOWAS and SADC have experienced regional interventions in conflicts with initiatives led by regional hegemons, the case of ECCAS has been so different with no state in the region having acted as a hegemon to intervene in conflicts. This points to the assertion that no hegemon has emerged in the ECCAS sub-region and this paper seeks to look at why no powerful states exist with the desire to intervene in conflicts in the Central African region.

The collapse of the Cold War order created new internal and external challenges for African states.[iv] The debt crisis, inter- and intra-state conflicts, coupled with problems arising from the forces of globalisation and marginalisation, global pandemics like HIV/AIDS and general human insecurity on the continent are among the challenges with which African states have been confronted.[v] The end of the Cold War also saw a change in how the US related to issues on the African continent. This was evident with its reluctance to intervene and help Liberia in 1989 and Rwanda in 1994. This reluctance is also evident in Africa to date where the US mostly sends support to fight its ‘wars on terror’ and is reluctant to intervene in other conflicts that destabilise the region and continent as a whole, a responsibility it possesses as a global hegemon stabilising the international system irrespective of the historic US-Liberian relations. No real help came from the USA to stop the 1989–96 Liberian crises.[vi] American forces were deployed to rescue Americans and other foreigners abandoning Liberia to disintegrate into further crisis.[vii] Thus, the limited impact of the USA and Russia in Africa since the end of the Cold War had created a power vacuum within this region so that regional hegemons had to fill and play the pivotal role of restoring peace in their sub-region from the 1990s onwards.[viii]

This paper seeks to advance an explanation for the absence of a dominant state (regional hegemon) in the Central African sub-region to promote peace and stability. To arrive at this explanation, section two examines and critiques a key argument in hegemonic stability theory. Using primary and secondary data sources, the paper’s third section examines the rationale for the absence of a regional hegemon in the Central African region. Data collected will be from secondary sources and will consist of reviews of books, journal articles and official reports. The final part concludes with the factors responsible for the absence of a regional hegemon in Central Africa

Hegemonic Stability Theory

Originally articulated by Kindleberger,[ix] who applied it to the rise and decline of US influence in international politics, the theory of hegemonic stability has since gained legitimacy in the works of several other prominent scholars like Keohane,[x] Modelski,[xi] Krasner,[xii] Gilpin[xiii] and Gadzey.[xiv] Kindleberger argued that inter-national free trade was a public good and its reliable supply depended on the existence of a hegemonic state. In Kindleberger’s words, ‘for the world economy to be stabilized, there has to be a stabilizer, one stabilizer.’[xv] While his work does not directly mention hegemonic stability, his postulations would lead to the emergence of this theory in political science circles. He claims that the Great Depression only occurred because the hegemon at the time, which to him was the US, failed to make the necessary sacrifices to preserve an open international economic system.

Since different states have different economic measures of what satisfies their interests, the hegemon must make arrangements that maintain an open trading order, otherwise states will erect trading barriers and the economic system eventually breaks down.[xvi] In maintaining the liberal economic order, the hegemon has to assume five responsibilities in periods of economic crisis that comprise of maintaining an open market for distress goods; providing long term lending during recessions; providing a stable system of exchange rates; coordinating macroeconomic policies; and being a lender of last resort.

For Kindleberger, only a hegemon is able to assume these duties at its own cost and this is because no other state has enough absolute power to do so. He however also doubts that a group of states can be able to stabilise the international trading system and suspects that such cooperative arrangements would likely fail.[xvii]

Being a multifaceted and complex concept, hegemony means different things to different scholars and this paper adopts the realist variant of the theory. For Schmidt, the realist variant of hegemonic stability theory attempts to tie together the two components of hegemony which are preponderant power and the exercise of leadership.[xviii] Lake believes the hegemonic stability theory consists of two, analytically distinct theories: leadership theory and hegemony theory.[xix] Hegemonic stability theorists start by postulating the presence of a single dominant state. According to Keohane, the theory of hegemonic stability ‘defines hegemony as preponderance of material resources’. He identifies four sets of resources hegemonic powers ought to have control over to be raw materials, sources of capital, control over markets, and competitive advantages in the production of highly valued goods.[xx]

Hegemonic stability theory purports that one important function of a hegemon is the guaranteeing of international order by creating international institutions and norms that facilitate international cooperation. The creation of international regimes is often a function of the presence of a hegemon who is willing to act in a collectively beneficial manner.[xxi] The presence of a hegemonic regime can ultimately produce stability and security. As such, the hegemonic stability theory assumes that during times of global economic growth and prosperity, a dominant state plays a hegemonic role in the international system. This therefore creates a link between periods of hegemony and stability.[xxii]

In War and Change in World Politics, Gilpin explains that systemic change leads to rise of hegemons in international systems.[xxiii] He assumes that the state is the dominant actor in the international system characterised by anarchy. In an anarchical world with few state actors, states are compelled to maximise their relative power over other states in order to ensure their own security and systemic change is therefore only produced by hegemonic war fought by all of the most powerful states in the world in order to gain dominant control of or maintain the ability to structure the international system. Following a hegemonic war, and the establishment of regimes that structure the power of the international system, the relative power of the hegemon decreases over time as both internal and external factors cause a reduction in the hegemon’s economic surpluses. The difficulty to expend resources and maintain the system causes rising non-hegemons to begin questioning its hegemony and this can lead to war with a possible new order emerging.

Hegemonic stability theory, according to Keohane, ‘holds that hegemonic structures of power, dominated by a single country, are most conducive to the development of strong international regimes whose rules are relatively precise and well obeyed.’[xxiv] The functioning of a liberal, open economic order is contingent upon the existence of a hegemon who is willing to exercise the necessary leadership to maintain the system. Nye argues that ‘economic stability historically has occurred when there has been a sole hegemonic power.....Without a hegemonic power, conflict is the order of the day’.[xxv] Economic stability is only possible when there is peace and this is relatively absent all over the sub-region. Wohlforth posits that unipolarity is a stabilising force (he conceives stability to be peacefulness and durability). Three points are used to advance his argument; the United States is a unipolar power; unipolarity is peaceful; unipolarity is durable.[xxvi] For this to change, the power dynamics of the unipolar system would have to change, and no state or alliance of states seems to be in a position to do so. Wohlforth’s second point, the assertion that unipolarity is peaceful, is also grounded in the realities of power dynamics. He sees no other major power in a position to be able to challenge the US and win in a war with it. At the same time, unipolarity minimises security competition among the other great powers. Unipolarity is peaceful, then, because it reduces hegemonic rivalry and minimises uncertainty. Monteiro points out that this peacefulness only extends to the absence of conflict between great powers.[xxvii] Cooley, Nexon and Ward,[xxviii] Chan and Kai He,[xxix] and Karmazin and Hynek[xxx] speak of the possibilities of a hegemon being revisionist. Tendencies like this challenge the unipolarity and stability claims of Wohlforth.

Monteiro contends that unipolarity tends to pose problems for peace but this argument is yet to be tested in Africa for at no point in time has there been a sole hegemon on the continent.[xxxi] This statement by Nye[xxxii] is of relevance to this paper for it tries to show this reality within the case of the Central African region and the series of conflicts at play in the region where there does not exist economic stability.

The Hegemonic stability itself being a prominent theory in International Relations, discourse has not been immune to criticism. Scholars such as Joseph Nye and Olson have succeeded in making forceful counter-arguments against the hegemonic stability theory. Nye points out the erroneous ‘prediction of conflict’[xxxiii] which the theory implies. He clarifies this argument by expounding the US’s surpassing of Great Britain as the largest economy in the world in the 1880s, without any war and instability. But yet again, the United States and Britain had already clashed in wars before and could this not have already been a war between these two powers. Problematising the theory further, I ask if it is necessary for the war to take place only at the specific time as a new hegemon is emerging. I would argue that this does not have to be the case.

Olson[xxxiv] on his part argues that while the presence of a single hegemon stabilises the international system and fosters economic growth, a situation is created where the hegemon eventually bears more costs than benefits and this creates a situation whereby the weaker states in the systems benefit more than the hegemon. At this point, when the hegemon starts to question the fact that smaller states enjoy a ‘free ride’, the tendency might be for these smaller states to want to overthrow the hegemon as its relevance is only needed if they can enjoy the benefits its hegemony provides. Keohane, a key proponent of the theory, believes that the structure of hegemony provides benefits to most states most of the time and had never considered the aspect of rising cost for the hegemon. The possible exclusionary actions of the hegemon (sanctions regime) raise the need for revisiting the theory as implicit in this is the fact that some states will certainly not benefit from the established order, thereby rebelling against the hegemon.

Snidal[xxxv] argues that ‘the range of the theory is limited to very special conditions’, and suggests that the decline of a hegemonic power may demonstrate the possibility of a collective power. According to Snidal, the applicability of the theory can be challenged due to limitations and the theory only holds true empirically under special conditions. Tierney[xxxvi] argues that hegemonic stability theorists are wrong in assuming that unipolarity leads to a stable order. He argues that it is this contestation of unipolarity that compels the great power and other states to build an international order.

Our issue with the criticism of Snidal lies in the fact that even a collective power rise is being resisted already as with the case of the European Union (EU) where states like Hungary and the United Kingdom (UK) are already questioning the power of the collective over their sovereignty. This has led to the UK withdrawing from the EU. Two differences between a hegemon and the collective cooperation is that costs are expected to be shared collectively with sovereignty not being eroded. The challenge, however, as with the case of regional bodies in Africa, is that most countries rarely meet their own financial contributions, thereby prompting the states making large contributions to still dictate decision-making in these bodies and still act as hegemons.

Conceptualising regional hegemons, Lemke believes them to be local dominant states supervising local relations by establishing and striving to preserve a local status quo.[xxxvii] Regional hegemons can be identified by the assumption of a stabilising and leading role, and the acceptance of this role by neighbouring states. Similarly, regional hegemons, or what are sometimes termed ‘regional leading powers’, have also been conceived as states that are influential and powerful in certain geographic regions or sub-regions.[xxxviii] For Ogunnubi & Okeke-Uzodike, regional powers not only possess superior power capabilities and exercise leadership within the region but are also able to convince other states (both within the region and beyond) to accept their leadership.[xxxix]

Flemes distinguishes regional hegemons by using four vital components which are a claim to leadership, power resources, employment of foreign policy instruments and acceptance of leadership. Accepting the role of regional leadership implies that the state in question has taken upon itself the responsibility of entrenching peace and stability and crafting policies for economic initiatives.[xl]

Power is a precondition for hegemony. Nye[xli] claims the sources of hegemonic power include (i) technological leadership, (ii) supremacy in military and economy, (iii) soft power and (iv) control of the connection points of international communication lines. Strange identifies four factors she claims in international political economy: the nation which has those elements more than the others is the most powerful; a state must sustain the capability to influence the other states via threats, defense, denial or escalation of violence; it must enjoy control of goods and service production systems; it should hold the authority of determination and management possibilities in finance and credit institutions; and it must also retain the most effective instruments to influence the knowledge and informatics either technically or religiously through acquiring, production and communication.[xlii]

While major superpowers have for a long time possessed these factors to dominate globally, there is a growing trend for regional hegemony as well, and understanding of how these capabilities are distributed among ECCAS states will enable a clear understanding of why no hegemon exists in the region.

2. Overview of the Central African Region

Central Africa is a region in Africa which is composed of different countries depending on the source of information. The geographical layout of the region differs from its memberships in diverse regional economic bodies as some geographically located Central African countries choose to belong to economic groupings outside the region. In a bid to clear up this ambiguity, the region will be looked at with respect to the regional body that exists in the region (ECCAS). Based on ECCAS membership, the Central African region comprises of the following countries: Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, DRC, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Rwanda, and São Tomé and Príncipe. Being from regions where all countries had been former colonies, the states have often had to grapple with issues of nation building in a multinational context. Below is an overview of Central African states’ country profiles.

Figure 1: Map of Africa highlighting Central African States

Table 1: Material resources of Central African States (To indicate power ranking of the countries and material preponderance)

|

Material Resources |

Angola |

Burundi |

Cameroon |

CAR |

Chad |

Congo |

DRC |

E. Guinea |

Gabon |

Rwanda |

STP[i] |

|

Military Military expenditure (US$ million) 2018 |

2508 |

67 |

405 |

28 |

216 |

273 |

267 |

NA |

240 |

119.5 |

NA |

|

Reg. ranking[ii] |

1 |

8 |

2 |

9 |

6 |

3 |

4 |

– |

5 |

7 |

– |

|

Total armed forces (000) 2019 |

107 |

NA |

14.5 |

7.1 |

30.5 |

10 |

134 |

NA |

5 |

NA |

NA |

|

Reg. ranking |

2 |

– |

4 |

6 |

3 |

5 |

1 |

– |

7 |

– |

– |

|

Energy Oil production (million barrels/day) 2018 est. |

1.6 |

0 |

0.069 |

0 |

0.13 |

0.34 |

0.017 |

0.17 |

0.19 |

0 |

0 |

|

Reg. ranking |

1 |

- |

6 |

- |

5 |

2 |

7 |

4 |

3 |

- |

- |

|

Natural gas production (billion cm) |

3.1 |

0 |

0.9 |

0 |

0 |

1.38 |

0 |

6.1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Reg. ranking |

2 |

- |

4 |

- |

- |

3 |

- |

1 |

5 |

- |

- |

|

Economy GDP (US$ billion) 2018 |

105.7 |

3 |

38.5 |

2.3 |

11.3 |

11.2 |

47.2 |

13.3 |

17 |

9.5 |

0.42 |

|

Reg. ranking |

1 |

9 |

3 |

10 |

7 |

6 |

2 |

5 |

4 |

8 |

11 |

|

Global Competitiveness Index Rank 2018 |

137 |

136 |

121 |

NA |

140 |

NA |

135 |

NA |

NA |

108 |

NA |

|

Reg. ranking |

5 |

4 |

2 |

– |

6 |

– |

3 |

– |

– |

1 |

– |

|

Demographics Population (million) 2018 |

30.8 |

11.1 |

25.2 |

4.6 |

14.4 |

5.2 |

84 |

1.3 |

2.1 |

12.3 |

0.21 |

|

Reg. ranking |

2 |

6 |

3 |

8 |

4 |

7 |

1 |

10 |

9 |

5 |

11 |

|

Land area (thousand sq. km) |

1,246,700 |

27,834 |

475,442 |

622,984 |

1,284,000 |

342,000 |

2,344,858 |

28,051 |

267,668 |

26,338 |

964 |

|

Reg. ranking |

3 |

9 |

5 |

4 |

2 |

6 |

1 |

8 |

7 |

10 |

11 |

|

Overall ranking |

17 = 1 |

NA |

29 = 3 |

NA |

33 = 4 |

NA |

19 = 2 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Source: author’s compilation

From the resource capabilities of these states, it becomes clear that some of these countries like Angola actually experience political stability and economic growth, and despite having the military capabilities as well to project hegemony these states do not do so. While the theory of Hegemonic Stability and existing literature shows the reasons for and benefits of hegemony, this region seems to have no state willing to act as a hegemon for reasons discussed below.

Reasons for Absence of a Hegemon in ECCAS

The absence of a regional hegemon in the Central African sub-region can be attributed to a plethora of factors

a. Multiplicity of Overlapping Regional Groupings

Although there exist a regional economic community, it is often the case that some Member States act in disregard to ECCAS agreements. In 2017, Cameroon ratified the Economic Partnership Agreement with the EU alone in disregard of agreements to negotiate with the EU within the framework of a regional grouping.[43] Individual state decisions like this undermine the integration efforts in the region and clearly show lack of state commitment to foster regional growth and trade protections for other Member States. States that stand to benefit most from collective regional development should have interests in being hegemons as this works for their good generally. An emergent China has an interest in being the hegemon because in so doing, it has smooth trading relations in the entire region and this translates into improved welfare domestically. Ensuring that regional security and trade issues are tackled effectively will ensure stability and the smooth function of the economies of Member States.

While other regional blocs in the continent are signing Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) as a bloc, Cameroon went ahead to sign on an individual basis and remains the only country in the region thus far to have signed. The multiplicity of membership in regional organisations among some Member States in the region makes it difficult for leadership to be committed towards acting as hegemon in one particular region. There exist an array of overlapping memberships among Member States in the region in different regional organisations. ‘Cameroon’s signing of the agreement constitutes a great threat to regional integration’, says economist Dr Ariel Ngnitedem, and Mbom notes that ‘It might destroy regional integration especially if the EU fails to reach a regional agreement with the CEMAC[44] countries.’ [45]

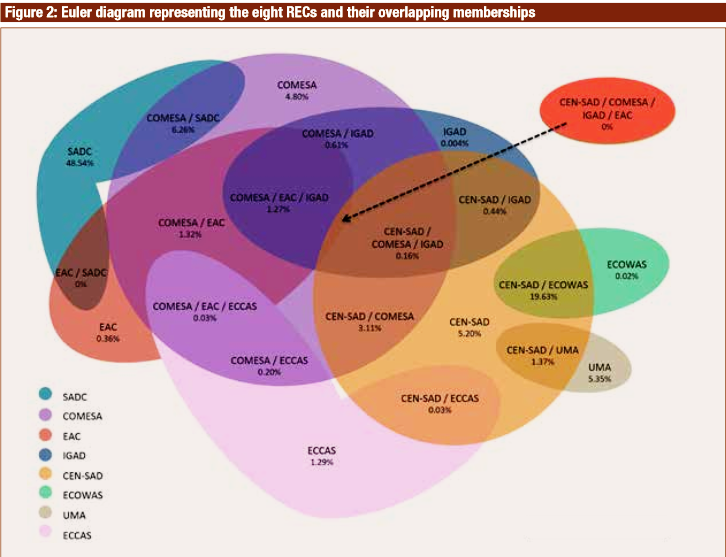

Figure 2: Map of regional communities in Africa with overlapping memberships.[46]

Countries like Angola and the DRC are members of both ECCAS and SADC; the DRC is also a member of COMESA.[47] Rwanda and Burundi are both members of ECCAS, COMESA and the EAC.[48] Chad is a member of ECCAS and CEN – SAD.[49] Even within the ECCAS community, there still exists another sub-regional community – CEMAC[50]. This union is composed of six Central African states – Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon. This multiplicity of group membership has made political commitment to the region less significant among leadership in Member States.[51] With CEMAC having a common currency among its members, its members have economies which are rarely in sync with those of other ECCAS members and they make their decisions without consulting other Member States in the region. As the most stable power in the region, with the most resource capabilities,[1] Angola’s dual membership in ECCAS and SADC means it cannot devote its scarce resources effectively to ECCAS which as a regional grouping has virtually the same objectives as SADC. The inability of ECCAS to succeed as a regional body shows the lack as well of leadership to push the region forward. Every regional body has states willing to push the integration forward. South Africa performs this role effectively in SADC and Nigeria in ECOWAS, the weaknesses of ECCAS as the least effective regional body on the continent can be attributed to its lack of a regional hegemon to foster its growth.

b. Internal Political Instability in the Sub-region

All ECCAS Member States are either plagued with instability, repressive regimes or both. With the end of colonialism, most successive governments in this region have only sought to maintain themselves in power. This has led to a series of conflicts all over the region. Presently, Cameroon, the Central African Republic and the DRC are plagued with civil wars. A majority of countries in the region are faced with sit-tight leaders[52] who manipulate constitutions to stay in power.[53],[54] These internal problems make it difficult for these countries to be able to divert huge resources in exerting influence abroad as they need to run repressive machineries within their countries. Fighting internal conflicts on multiple fronts is so resource draining and does not afford states the time to even concentrate on external issues within the region. Some countries in the region claim their reluctance to project power is due to the respect of non-intervention principles. While the foreign policy directions of some states in this region (like Cameroon)[55] reflects that of non-intervention in the affairs of other states, this can also be attributed to the fact that repressive regimes invest much of their militaries and limited resources to oppress their citizens. The civil war in Angola ended in 2002, and as of now Angola has the most material resources to act as a hegemon; a role it has also proven reluctant to carry out.

c, The Neo-Colonial Hand

Neo-colonialism has been in existence since the independence of most African states as it serves to reduce resource capabilities and restrict the political will of leadership. One salient scholar who attempts captures this phenomenon is Nkrumah:

Once a territory has become nominally independent it is no longer possible, as it was in the last century, to reverse the process. Existing colonies may linger on, but no new colonies will be created. In place of colonialism as the main instrument of imperialism we have today neo-colonialism. . . . The essence of neo-colonialism is that the State which is subject to it is, in theory, independent and has all the outward trappings of international sovereignty. In reality its economic system and thus its political policy is directed from outside.[56]

Within the ECCAS region, this link is strong among the six Member States that make up CEMAC.[57] Using the CFA franc, the currency is pegged to the euro and the monetary policies are decided by France. In a relationship like this, most of these countries are not sovereign and as such cannot actually exercise hegemonic tendencies in the region. The CFA franc was initially pegged to the French franc and later to the euro, with the reserves of countries using this currency kept in Paris. The fiscal policies of these states are not even their making.[58] Other powerful states in the region like Angola will find it difficult attempting to exercise hegemony in the region as this will imply their likelihood of intervening in the affairs of Francophone countries. Such interventions will in essence threaten French interests in the region and in itself could cause conflicts.

These Francophone states are in effect handicapped as their foreign policy trajectories are not theirs to make, with most of their leaders being put and maintained in power by France. The actual power dominating the area is France and it would appear that French influence and interests prevent the emergence of a regional hegemon in the area with France effectively being the hegemon over the Central African region. France incessantly intervenes in these states and has for long been a mastermind of regime change in order to ensure it runs the affairs of its former colonies and the region.[59]

The most stable country in the region is Angola.[60] However, it is a member of both ECCAS and SADC, and a lack of resources means political commitments will hardly be effective to both organisations. The personal interests of Nigeria in ECOWAS and South Africa in SADC to intervene in regional conflicts is fairly absent in ECCAS as evident with the series of on-going conflicts with no state willing to intervene. While this lack of interests, internal economic instability and economic challenges all play a role in restricting the capabilities of states in the region to intervene, the neo-colonial influence in the region is the main reason for the absence of a local regional power with willingness to intervene in conflicts. French hegemony is still strong in the region and local states attempting to intervene could be seen as a desire to alter power dynamics. Theories of hegemonic stability do not account for neo-colonial interference among independent nations in the Central African sub region. While regions like Southern Africa have hegemons, the interference of France in Central Africa can also clearly explain the lack of a hegemon in the sub region.

Hegemonic stability theory requires for a state to possess the capability to enforce the system, the will to do so and a commitment to a system which is perceived as mutually beneficial to the major states. Regionalism in Africa is defined by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and not by member countries. The decisions of states like Angola, Burundi, the DRC and Rwanda to join integration schemes in other parts of the continent show that these states are redefining the rules they want to be subjected to and do not believe the existing rules in ECCAS are mutually beneficial. The presence of other integration schemes inside the ECCAS community further highlights this lack of the belief in mutually beneficial rules within ECCAS. While states like Angola possess the capabilities to serve as regional hegemons within the region, they have not demonstrated the will to do so and it would rather be a member of SADC where South Africa is clearly the Hegemon. Behaviour like this would suggest that maybe states in this region just do not want to intervene and play hegemonic roles as they come with costs of possible instabilities with external countries like France.

Conclusion

Co-operation among states in the region has also overshadowed the ability for a hegemon to emerge as regional organisations like ECCAS and the Economic and Monetary Community of Central African states work to provide the services of a hegemon. Alan James also makes a purposive proposal, which identifies an international system comprising co-operating states, rather than a global hegemon establishing and enforcing rules and regulations. As James puts it: ‘Co-operative activity, in short, does not necessarily imply that the co-operating actors somehow fade into the background; in practice it does not have this effect and it is hard to see how it could possibly do so.’[61] This quotation therefore elucidates effectively, the interpretation that states will act on the necessity to co-operate with other states, but this by no means implies that the sovereignty of the individual states is compromised and a hegemon is established. Within the framework regional organisations, cooperative activity can also serve as a source of stability and this has been seen in the Southern African region for a long time, with recent instability threats being met by the deployment of a regional force.

Regional hegemons play significant roles in peace and stability within the African continent. The African Union and the UN Economic Community for Africa have also underscored the relevance of hegemons in promoting regional cohesion and trade integration among the Regional Economic Communities.[62] Salient examples of countries like Nigeria in ECOWAS and South Africa in SADC have been instrumental in performing these roles. The study sought to find out the reasons for why there is no regional hegemon in Central Africa and after building up on and analysing the material resources of the ECCAS Member States, I concluded that the absence of a hegemon was as a result of multiplicity of regional organisations in Central Africa, domestic political environment, economic challenges and the neo-colonial hand. While the study argues for these reasons, it is also important to note that the main player in the region is France and its activities and interests would conflict with that of a regional hegemon (should one emerge now) for there is no explaining power politics in Francophone Africa without mentioning France.

Endnotes

[1] Vines, A. & Weimer, M. (2011). Angola: assessing risks to stability. Report of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Accessed on 12/15/2019 at https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/publication/110623_Vines_Angola_Web.pdf.

[i] Adebayo Oyebade & Abiodun Alao (eds.) (1997). Africa after the Cold War: The changing perspective on security. Africa World Press.

[ii] Melander, E., Pettersson, T. & Themnér, L. “Organized Violence, 1989-2015.” Journal of Peace Research 53, no. 5 (2016): 727-42.

[iii] Democratic Republic of Congo

[iv] Ojakorotu, V. & Adeleke, A. A. (2017). Nigeria and Conflict Resolution in the Sub-regional West Africa: The Quest for a Regional Hegemon? Insight on Africa, 10(1), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0975087817735386.

[v] Akokpari, J. (2001). Post-Cold War international relations and foreign policies in Africa: New Issues and New Challenges. African Journal of International Affairs (AJIA) 4(1–2), 34–55.

[vi] Ojakorotu & Adeleke, Nigeria and Conflict Resolution in the Sub-regional West Africa: The Quest for a Regional Hegemon?

[vii] Copson, R. W. (2007). The United States in Africa: Bush policy and beyond. Zed Books.

[viii] Adebajo, A. & Landsberg, C. (2003). South Africa and Nigeria as regional hegemons. In M. Baregu, C. Landsberg, (eds.), From Cape to Congo: Southern Africa’s Evolving Security Challenges, 171–203. Lynne Rienner.

[ix] Kindleberger, C. (1973). The world in depression 1929-1939. University of California Press.

[x] Keohane, R. O. (1980). The Theory of Hegemonic Stability and Changes in International Economic Regimes, 1967-1977. In O. R. Holsti et al. (Eds.). Change in the International System. Boulder: Westview Press.

[xi] Modelski, G. (1987). Long cycles in world politics. University of Washington Press.

[xii] Krasner, S. D. (1983). Structural causes and regime consequences: Regimes as intervening variables. In S. Krasner (ed.). International regimes. Cornell University Press.

[xiii] Gilpin, R. (1987). The political economy of international relations. Princeton University Press.

[xiv] Gadzey, A. T. (1994). The Political Economy of Power: Hegemony and Economic Liberalism. New York: St. Martin's Press.

[xv] Kindleberger, The world in depression 1929-1939, pp, 305.

[xvi] Kindleberger, The world in depression 1929-1939.

[xvii] ibid

[xviii] Schmidt, B. (2018). Hegemony: A conceptual and theoretical analysis. Governance and Diplomacy Expert Comments. Dialogue of Civilizations Research Institute. Retrieved on September 26th 2019 from https://doc-research.org/2018/08/hegemony-conceptual-theoretical-analysis/

[xix] Lake, D. A. (1993). Leadership, hegemony, and the international economy: Naked emperor or tattered monarch with potential? International Studies Quarterly 37(4), 459–489.

[xx] Keohane, (1984). After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

[xxi] Krasner, Structural causes and regime consequences: Regimes as intervening variables.

[xxii] Ogunnubi, O. (2016). Effective hegemonic influence in Africa: An Analysis of Nigeria's ‘hegemonic’ position. Journal of Asian and African studies, 52(7), 1-15.

[xxiii] Gilpin, R. (1981). War and Change in World Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[xxiv] Keohane, The Theory of Hegemonic Stability and Changes in International Economic Regimes, 132.

[xxv] Nye J. S. (1990). The changing nature of American power. Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 105, No. 2 (Summer, 1990), pp. 177-192.

[xxvi] Wohlforth, W. C. (1999). The stability of a unipolar world. International Security. 24(1), 5-41.

[xxvii] Monteiro, N. P. (2014). Theory of unipolar politics. Cambridge University Press.

[xxviii] Cooley, A., Nexon, D. & Ward, S. (2019). Revising order or challenging the balance of military power? An alternative typology of revisionist and status-quo states. Review of International Studies, 45(4), 689–708.

[xxix] Chan, S. & Kai He, W. (2018). Discerning States’ Revisionist and Status-quo Orientations: Comparing China and the US. European Journal of International Relations. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066118804622.

[xxx] Karmazin, A. & Hynek, N. (2020). Russia, US and Chinese Revisionism: Bridging Domestic and Great Power Politics. Europe-Asia Studies, 72(6).

[xxxi] Monteiro, Theory of unipolar politics.

[xxxii] Nye, The changing nature of American power.

[xxxiii] Nye, J. S. (2000). Understanding International Conflicts. New York: Longman, pp. 59.

[xxxiv] Olson, M. (1965). The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[xxxv] Snidal, D. (1985). The limits of hegemonic stability theory. International Organization, 39, 579-614.

[xxxvi] Tierney, D. (2021). Why Global Order Needs Disorder. Global Politics and Strategy, 63 (2):115-138.

[xxxvii] Lemke, D. (2002). Regions of war and peace. Cambridge University Press.

[xxxviii] Nolte, D. (2010). How to compare regional powers: analytical concepts and research topics, Review of International Studies, 36, 883.

[xxxix] Ogunnubi, O. & Okeke-Uzodike, U. (2016). Can Nigeria be Africa's hegemon? African Security Review, 25(2), 110-128. DOI: 10.1080/10246029.2016.1147473.

[xl] Flemes, D. (2007). Conceptualising regional power in international relations: lessons from the South African case. Working Paper No. 53. German Institute of Global and Area Studies.

[xli] Nye, J. S. (2003), The paradox of American power: Why the world's only superpower can't go it alone. Oxford University Press.

[xlii] Strange, S. (1987). The persistent myth of lost hegemony. International Organization, 41(4), 551-574, pp 565.

[43] Nsaikila, M. (2016). The Economic Partnership Agreement Goes into Effect – What’s at Stake for Cameroon. Accessed on November 18 2019, at https://www.foretiafoundation.org/the-economic-partnership-agreement-goes-into-effect-whats-at-stake-for-cameroon/

[44] Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa

[45] Mbom, S. (2018) Cameroon goes it alone with controversial EU trade deal, angers regional partners. African arguments. Accessed on November 18 2019, at https://africanarguments.org/2016/09/26/cameroon-goes-it-alone-with-controversial-eu-trade-deal-angers-regional-partners/

[46] UNCTAD, (2018). From regional economic communities to a continental free trade area: Strategic tools to assist negotiators and agricultural policy design in Africa. UNCTAD/WEB/DITC/2017/1, Available at https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/webditc2017d1_en.pdf

[47] Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa

[48] East African Community

[49] Community of Sahel – Saharan States

[50] Economic and Monetary Community of Central African States

[51] The Political Economy Dynamics of Regional Organisations report by European Centre for Development Policy Management, available at https://ecdpm.org/wp-content/uploads/ECCAS-CEMAC-Policy-Brief-PEDRO-Political-Economy-Dynamics-Regional-Organisations-Africa-ECDPM-2017.pdf

[52] São Tomé and Príncipe has experienced smooth transitions since the introduction of multi-party politics in 1991, the DRC just got a new leader replacing Kabila and the CAR is in crisis with a new leader as well. All the other states have sit-tight leaders.

[53] Oyewo, A. T. (2014). Examination of the Root Causes of Unsustainable Development in Africa. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 16(4), 44-56.

[54] Abiodun, T. F. Nwannennaya, C. Ochie, B. O. & Ayo-Adeyekun, I. (2018). Sit-Tight Syndrome and Tenure Elongation in African Politics: Implications for Regional Development and Security. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science (IOSR-JHSS), 23(4), 59-65.

[55] Chatham House (2013). Cameroon across the Divide: Foreign Policy Priorities in West and Central Africa. Interview with Cameroon’s Minister of External Relations, Pierre Moukoko Mbonjo. Accessed on November 18 2019, at https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/Africa/020913summary.pdf

[56] Nkrumah, K. (1965). Neo-Colonialism, The Last Stage of Imperialism. Thomas Nelson & Sons, Ltd.

[57] This monetary union is made of countries that use the CFA franc currency and the reserves of this currency are kept in the French treasury in France.

[58] Sylla, N. S. (2017). The CFA Franc: French Monetary Imperialism in Africa. Review of African Political Economy, available at https://roape.net/2017/05/18/cfa-franc-french-monetary-imperialism-africa/.

[59] Banlilon, V., Sunjo, E. & Abangma, J. (2012). Furthering regional integration in the face of the conflict and security challenge in Central Africa. Tropical Focus, 13(1).

[60] Sören, S. (2017). Secondary Powers vis-à-vis South Africa: Hard Balancing, Soft Balancing, Rejection of Followership, and Disregard of Leadership, GIGAWorking Papers, No. 306, German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg.

[61] James, A. (2000). Issues in International Relations, ed. Trevor Salmon. London: Routledge, pp. 22

[62] Merran, H. (2016). Regional Powers and Leadership in Regional Institutions: Nigeria in ECOWAS and South Africa in SADC, KFG Working Paper Series, No. 76, November 2016, Kolleg-Forschergruppe (KFG) “The Transformative Power of Europe“, Freie Universität Berlin.