Abstract

This article seeks to analyse the process of conflictual rebordering in the EU's relations with Russia. The authors single out three major crises that triggered and shaped the process of toughening the border regime and the related transformations of political meaning of the EU-Russia border: the COVID-19 pandemic, the drastic deterioration of Moscow-Brussels relations in the beginning of 2021 and the war in Ukraine that started on 24 February 2022. Correspondingly, the EU’s reactions to each of these critical junctures might be described through the academic concepts of governmentality, normativity and geopolitics. Our aim is to look at the three ensuing models – governmental, normative and geopolitical rebordering – from the vantage point of Estonia and Finland, two EU member states sharing borders with Russia, yet in the meantime remaining distinct from each other in developing particular border policies and approaches vis-a-vis their eastern neighbour.

Keywords

Introduction

In only a decade, EU-Russia relations have degraded from a multi-dimensional institutional partnership to a standoff followed by a deep freezing of almost all policy tracks after Russia’s invasion in Ukraine on 24 February 2022. The EU reacted by applying sanctions to make Russia pay a dear price for deviation from international norms and as an instrument for containing Russia, to which the Kremlin responded with a complete disruption of relations with Brussels as a key element of Russia’s strategy of unconstrained freedom to act at its own discretion.

In this article we look at the deterioration of Russia’s relations with the EU through the prism of three constitutive events. First, the coronavirus crisis has aggravated the frigid EU-Russia coexistence. Russia’s and the EU’s crisis management strategies were largely detached from each other (Baunov 2021) which expanded the space for conflictuality. The border closure between Russia and the EU in March 2020 looked like a metaphorical completion of the whole cycle of confrontation, symbolically marking the descending trajectory of relations. The lockdown provoked by COVID-19 duly reflected the state of bilateral relations: Europe did not trust Russian official statistics (from electoral to medical), while Russia did not seem to be interested in discussing conditions for a full border reopening with Brussels. In this sense, COVID-19 has proved that Europe can live apart from Russia, and that many Putin sympathisers have apparently overrated the indispensability of Russia for the entirety of the EU.

The second crisis erupted due to the arrest of Alexei Navalny, Russian opposition leader, on his way back to Moscow in January 2021 after being poisoned in Russia and then medically rehabilitated in Germany. A particularly significant sign of the aggravation of tensions between Moscow and Brussels was Josep Borrell’s visit to Russia in February 2021, and its controversial echoes that have incited a chain of events consequential for the EU’s relationship with Russia.

Thirdly, Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has exposed a clash of two fundamentally different conceptions of power in international relations. On the side of the Euro-Atlantic West, power is inherently normative and institutional, and is based on shared principles and rules supporting them by the governmentality of multilateral organisations that prioritise technocratic, legalistic and utilitarian policies over transgressive, revisionist and potentially dangerous politics of sovereign reason. Never before has the contrast between the two philosophies of power been so lucid. By the same token, Russia’s war against Ukraine has demonstrated the distinction between NATO members (such as the Baltic and Central European states) and non-members such as Ukraine, as well as Georgia invaded by Russia in 2008. The decision of Sweden and Finland to apply for NATO membership was a clear indication of a change in structural conditions of security, where governmentality can no longer mitigate geopolitical concerns and is thus shrinking under the pressure of sovereign power.

The borderland location is a politically important factor in each of these conflicts and crises, since some of Russia’s neighbours claim to possess a unique experience with Russia, yet in the meantime they are the most vulnerable to Russia's policies. Two countries – Finland and Estonia – exemplify this ambiguity. On the one hand, both tried to maintain a space for national diplomacies towards Russia: the Finnish foreign minister visited St. Petersburg in the immediate aftermath of Borrell’s failure in Moscow, and the Estonian government that came to power in January 2021 has demonstrated its willingness to restart negotiations with Moscow on the border treaty. On the other hand, structural distinctions between Finland and Estonia are lucid. The former has used its border location for managing the Northern Dimension programme as a multilateral instrument for engaging Russia and its north-west regions in environmental, educational and people-to-people contacts, while the latter has always been trying to persuade its Western partners to reconsider their idealistic perceptions of Russia. The roots of these distinctions are structural and date back to the fall of the Soviet Union that brought economic losses to Finland and political freedom to Estonia. Multiple asymmetries between these two culturally and geographically close neighbours elucidated a strategic importance of balancing sanctions as a deterrence tool with safeguarding unity of EU diplomacy, as well as between harsh criticism of Russia and maintenance of bilateral tracks of relations with Moscow.

Therefore, the overall research puzzle we tackle in this article is how different logics and the ensuing discourses – geopolitical, normative and governmental – shape Russia policies of Finland and Estonia? How may these logics be conceptualised, and what does the imbrication of these logics imply for the two countries? How does the conflation of different rationalities dislocate foreign policies of the two countries? A related puzzle deals with the explanatory potential of the three logics regarding discrepancies between the EU’s external relations and bilateral contacts of the member states with Russia.

By looking at the interaction of Finland and Estonia with their common eastern neighbour, we want to expose distinctions between the two countries that share common institutional (EU membership and the ensuing normative regulations) and geolocational characteristics. Our theoretical approach allows us to capture the patterns of each country’s Russia policy through a combination of certain logics that sometimes operate in unison and overlap, and sometimes contradict each other, thus creating a room for manoeuvre. For this reason, our paper seeks not only to compare the two given countries, but also to broaden the academic discussion on the variability of possible strategies of bordering and re-bordering that are simultaneously affected by geopolitical tensions, national priorities and member states' commitments to EU policies.

Materials and methods

The research is based on an analysis of three critical moments – the border lockdown due to the pandemic, Navalny's imprisonment and the invasion of Ukraine in 2022. We study Finnish and Estonian reactions and approaches to these events and their adjustment to the border policies with Russia. To do so, we draw on discourse analysis of governmental reports and official statements derived from open sources of information such as:

- the websites of official bodies: the Library of Parliament (Eduskunnan kirjasto), Finnish Government (Suomen valtioneuvosto), Estonian Government (Eesti Vabariigi Valitsus), Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Välisministeerium) and Permanent Mission of Estonia to the UN;

- the key news media in Finland and Estonia: Yle Uutiset (http://yle.fi/), Helsingin Sanomat (https://www.hs.fi) and ERR (https://news.err.ee/);

- and findings from previous fieldwork and the interviews collected in Lappeenranta in February-March 2019 for the Finnish case of border governance.

In addressing these debates, we treated them as discourses that construct the multiplicity of actors with their governmental and security practices. We seek to explore how these discourses articulate Russia as a geographic neighbour for Finland and Estonia, and how Russia unfolds discursively in the contexts of various logics and rationalities and official pronouncements. Our study is limited to the period of the escalation of three critical junctures, that is from March 2020 when the first measures of border lockdown were put in place till May 2022 when Finland (along with Sweden), enthusiastically supported by Estonia, applied for NATO membership.

The three critical junctures and the logic of escalation

In this section, we discuss how three crises – the coronavirus pandemic, the political aggravation of Russia-EU relations in the aftermath of the Navalny case and Russia’s aggression against Ukraine – can be approached from the viewpoint of trans-border relations.

The biopolitical lockdown

The ongoing conflict between Russia and the West was complicated by COVID-19, particularly by the unprecedented border lockdown and Russia’s complaints about the EU’s hesitance to accept the Sputnik V vaccine. The gaps between Russia and the EU in tackling COVID-19 can be discerned while looking at the major foreign policy tenets of both parties. As seen from the Russian dominant perspective, globalisation is in crisis, and the pandemic paved the way for a return to national policies and sovereignties. In the Russian interpretation, COVID-19 showcased vulnerabilities of liberal democracies, questioned the idea of liberal internationalism and proved the effectiveness of unilateral actions and bilateral deals. Russian diplomacy tried to use the pandemic to prevent a return to a normative and value-based structure of international relations, and therefore to blur the lines between liberal and illiberal regimes, as well as between democracies and non-democracies, which – in this interpretation – makes all regimes similar to each other, since all the affected countries have to resort to deviations from classic democracy. The Western liberal order, in the eyes of Putin and his associates, does not have competitive advantages over illiberal regimes when it comes to the life protection function (Trenin 2020). Generally, Russia is interested in capitalising on the shifting attention from such issues as the war-by-proxies in Donbas or the annexation of Crimea, to health diplomacy and the mutual recognition of vaccines.

The EU approach is grounded in a different set of premises. Despite all setbacks in the COVID-19 crisis management, the EU stood strongly for global coordination policies exemplified by its contribution to the COVAX initiative. The Commission and member states have taken a common EU approach to securing supplies and facilitating the rollout of vaccines as practical implementations of liberal internationalism.

When it comes to practicalities, during the pandemic Russia tried to diversify its foreign policy toolkit. Putin proposed lifting international sanctions against the most badly affected countries, but it went unnoticed. More visible were performative actions of Russian ‘health diplomacy’ in Italy and Serbia in spring 2020. In 2021 vaccine diplomacy became a new foreign policy tool to re-define the relations with ‘Europe’ (less with the EU and more with member states). In this context Russia found in the vaccine a new policy instrument that could allow the Russian state to reposition itself as a globally indispensable power possessing an effective cure against the deadly disease. However, a common EU-wide approach boiled down to accepting the Russian vaccine only after its certification by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Most EU member states, Estonia and Finland included, adhered to this norm aimed at what in a different context was called a ‘biopolitical demarcation of Europe’ (Baar 2017: 215). Therefore, the COVID-19 crisis has strengthened the cleavages between Russia and the EU, which was exemplified by Putin’s irritation with the reluctance of the EU authorities to accept Sputnik V beyond EMA regulations. In the meantime, the pandemic left it up to each specific country to construct their border policies along the lines of normative, geopolitical or governmentally biopolitical logics to be introduced later.

The Navalny crisis and its repercussions

Conceptually, this conflict has pitted the EU’s adherence to democratic norms and de-legitimation of autocracies, on the one hand, and Russia’s insistence on national sovereignty and the ensuing equality of all power holders, regardless of the nature of their political regimes, on the other. In a practical sense, at the centre of attention was the unfriendly treatment that the head of EU diplomacy received in Russia, including a well synchronised expulsion of European diplomats from Moscow. The EU has introduced a bunch of sanctions based on the EU Global Human Rights Sanctions Regime[1] that envisaged travel bans and the freezing of funds for individuals and entities associated with human rights violations. From its side, the Russian Foreign Ministry declared the president of the European Parliament David Sassoli and the EU commissioner Věra Jourová personae non gratae.

The tug-of-war between Russia and the EU over the imprisonment of Alexei Navalny was followed by harsh tensions between Prague and Moscow regarding Russian intelligence operatives involved in an explosion at a Czech arms depot in 2014 that killed two people. In May 2021, twelve European countries expelled Russian diplomats as a sign of solidarity with Czechia. Russia included Czechia, along with the United States, in a list of ‘unfriendly countries', a new concept in the Russian foreign policy toolkit. The coordinated attempt of Germany and France to replicate the Biden-Putin summit in Geneva with the symmetric move of inviting the Russian president to resume the tradition of EU-Russia summits was blocked by a consolidated position taken by Central European and Baltic states.

Russia’s war against Ukraine

From the viewpoint of the Russian mainstream discourse, the so-called ‘crisis’ in Ukraine was the ‘last drop’, the ‘final clarifying issue’, (Haukkala 2021: 196) that allegedly left Russia with no choice than to intervene, to which the EU, from its perspective, had to respond with sanctions. Under these conditions, the Russian policy is one of the few foreign policy domains where the EU does have a common approach. The institutional coherence shown by the EU put the Russian elite in a disadvantageous position: even the most Russia-friendly European governments voted for sanctions when it comes to their compliance with a shared policy of the Union. While Russia perceives sanctions as an illegitimate geopolitical tool, the EU sees them as a way to make Russia pay an economic price for deviation from normative rules of democracy and as an instrument of preventing Putin’s regime from undertaking other illegitimate actions in the future.

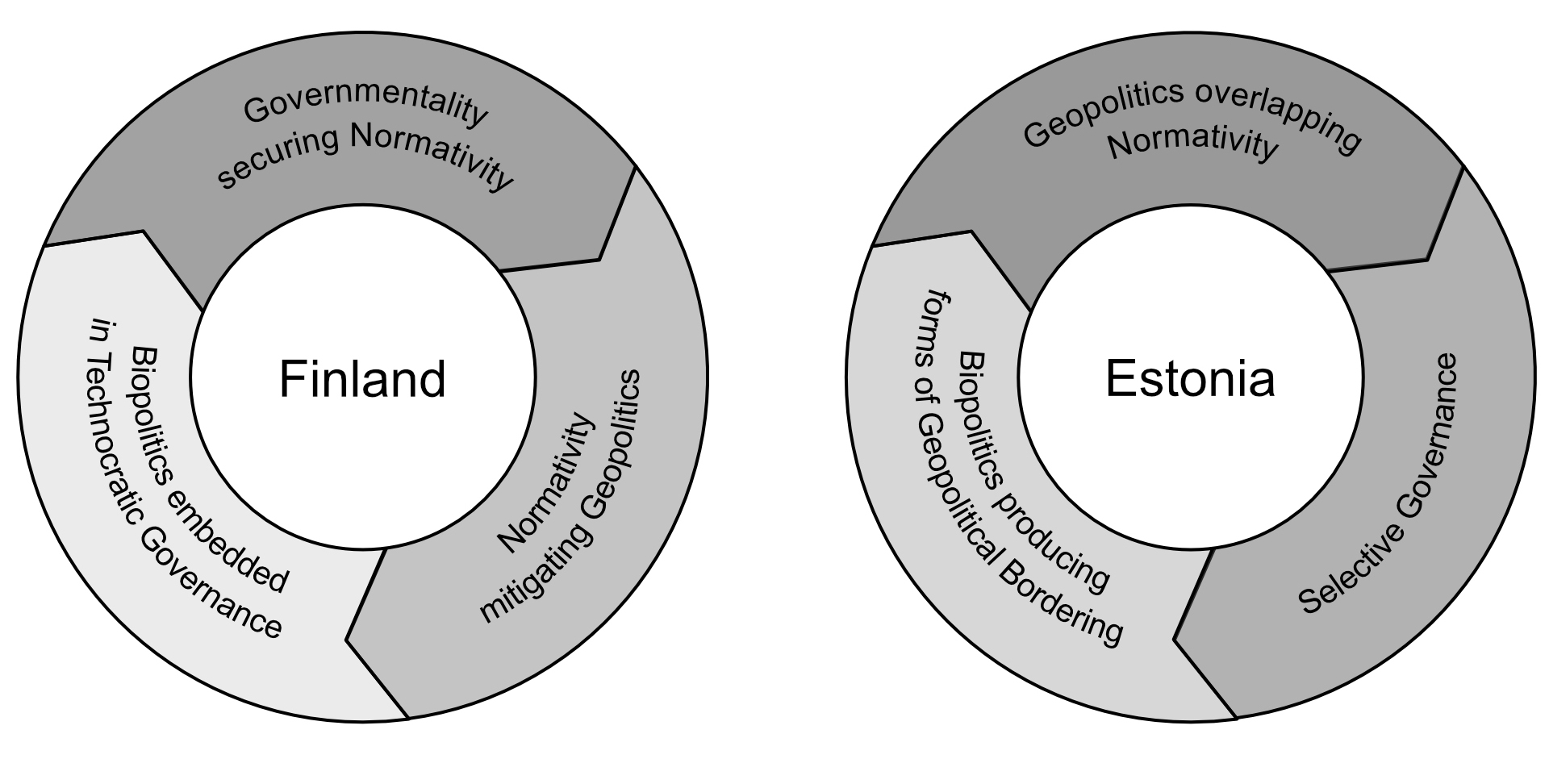

Based on empirical material, in the following section we show how the three events might be explained through three logics that intersect in Estonian and Finnish contexts expanding the room for policy manoeuvres (Pic.1). Our goal is to open these binarised conflicts to a discussion of three different logics or rationalities (in a Foucauldian sense) that shape policy choices of EU member states: geopolitics, normativity and governmentality. These logics manifest themselves through particular discourses that develop in parallel to each other, overlap or clash, thus producing various fields of tensions and hybridities. A pluralistic approach to the EU’s relations with Russia is particularly topical since, as some observers suggest, ‘in the absence of any improvement in Russia-EU ties in the short to medium-term, it might be pertinent to focus on building bilateral ties between Russia and individual European states’ (Kapoor 2021). This primarily concerns countries bordering Russia, since the deterioration of the Kremlin’s relations with the EU still leaves some space for interaction between neighbours. However, the critical state of EU-Russia relations creates a more fertile ground for multiple asymmetries in foreign policy tactics and diplomatic styles of countries sharing borders with Russia, which might be explained by a cleavage between the EU’s consolidated position on sanctions and the autonomy of each member state to conduct its trans-border policies, which creates some ambivalence within the EU, and allows each state to manoeuvre.

Fig 1. Display of mixed logics in Finland and Estonia

Source: authors

Introducing the three logics

In this section, we introduce the three logics constitutive for EU-Russia relations, explain how they overlap and discuss what policy effects they entail. None of these logics belong to a specific actor. They rather function as discursive fields in which different interpretations of values, spaces and governance interact with each other.

This taxonomy is grounded in the discussions on different dimensions of the EU power based on structures of international order (Wagner 2017). Our approach is consonant with the assumption that logics of power in EU-Russia relations can’t be reduced to a single category, and that different forms of power do not exclude each other (Casier 2018: 103-104). The simultaneous operation of different options of policies in general and bordering in particular creates certain ambiguity which in the meantime implies a ‘particular productive dynamic’ (Ahrens 2018: 203). Each logic is an intersubjective construct reshaped through interactions with actors beyond the liberal international order who might ascribe to the EU's normative or governmental policies geopolitical meanings (Michalski & Nilsson 2019: 445).

Let us start with the normative logic that in the EU’s interpretation is grounded in transforming international politics wherein normative commitments and value-based foreign policies play increasingly prominent roles. In the categories of the English school, this transformation might be described as a transition from an international system to an international society and then to an international community. This trajectory explains the prominence of the normative logic in EU foreign policy: the post-Cold War European order drastically changed the understanding of power from military force projection or economic coercion to sharing liberal norms, responsibilities and institutions through communication and engagement. The EU’s normativity envisages common or compatible values and identities, a post-national, post-sovereign, post-Westphalian, networked type of foreign policies, and a greater role for NGOs. The EU’s normative actorship presupposes that liberal norms define interests and gains, that these norms geographically expand and that the EU is a norm-projector, as exemplified by the Eastern Partnership (EaP) project. In this sense, the concept of normative power not only constructs the EU’s identity (Diez, Manners & Whitman 2011), but also defines the normal (and therefore the deviant) and implies a balance between normative ends and normative means, along with the ability to set a common normative agenda as a basis for the institutional power of multilateral diplomacy through a system of partnerships. Within this logic, the EU is a producer of various regional spaces premised upon a nexus between institutions and identities – the Northern Dimension, the EU’s Baltic Sea Strategy or the Black Sea Synergy.

This normative logic was unfolding in a sharp contrast with the Russian claim that integration into the Western-centric system of rules and values would not give Russia an unconditionally equal status, or what Russians prefer to dub ‘respect’. This explains a trajectory of Putin’s illiberal transition – from adaptation to the main principles of liberal democracy to its parodic imitation, then to contesting the very idea of norm-based international politics. The crucial component of this turn is the fascination with sovereignty and the ensuing reinterpretation of power as a type of material ownership and a physical possession of tangible and measurable resources, as opposed to the understanding of power as embedded in communicative and institutional relations. Russia’s disdain for normativity stems exactly from a disbelief in the possibility to derive power from immaterial sources – commitments to rules and values, techniques of good governance or communicative skills. The gap between the two political philosophies, normative (ideational) and realist (materialist), is one of the frontiers that delineates liberalism and illiberalism, and Russia under Putin has meaningfully contributed to the construction of this divide.

The conflictual interaction with Russia has reinvigorated the EU's geopolitical logic. Policy experts suggest that the EU and its major member states need to be more geopolitical and less ideational/‘romantic’ when dealing with Russia (Pishchikova & Piras 2017: 113). This perspective is rooted in the perception of the growing power of Russia, including Russia’s abilities to permeate and penetrate Europe from inside (through recruiting ex-politicians for lucrative jobs and support for anti-establishment parties), along with the fear that the EU’s intransigent normative position will ultimately push Russia towards an alliance with China. However, the EU’s geopolitics might be characterised as a ‘hybrid’ (Nitoiu & Pasatoiu 2020) realm of complex interactions between spatial/territorial/geographic calculations and normative agenda. Accordingly, the EU’s normative policies might have geopolitical effects since the EU's ‘productive/enabling power’ transforms its neighbours through the force of attraction and mechanisms of external governance and expands their scope of choices for the EU’s partners (Hyde-Price 2006).

The concept of governmentality is based on a Foucauldian legacy and can be regarded as a managerial response to problems that cannot be tackled through normative or geopolitical policy tools. The application of this concept to the sphere of border studies is marked by a duality. On the one hand, governmentality is usually discussed as a productive form of power aimed to achieve greater freedom through knowledge-based practices grounded in the logics of the market and liberal political economy. Governmentality operates through (self-)regulative incentives and implies risk assessment, calculation, best practices promotion, fostering competitiveness through indexing, benchmarking and other empowerment techniques. It exemplifies a technocratic model of steering, incentivising and rationalising policy making (Lemke 2013: 37). Governmentality tools do not impose coercive power but rather help to optimise limited resources. Governmental mechanisms incorporate communicative and transformational power with its spill-over effects in such policy spheres as anti-corruption, transparency and accountability, anti-discrimination, civil service, intellectual property, public procurement, environmental protection, energy efficiency and education (Dean 2010). The EU's agenda of external governmentality includes best practices transfer, learning at a distance and educational exchange programmes, along with measures of conflict reconciliation through dialogue and democratisation. Externalisation of norms includes transformative impact over neighbours, modernisation assistance with respective commitments (through conditionality), and visa liberalisation.

On the other hand, border governmentality implies certain forms of othering, which is illustrated by controlling cross-border immigration. In the terrain of the EU’s neighbourhood policy, the bordering function of governmentality seems to be quite important: in the European Neighborhood Policy (ENP) and EaP, political practices and their governmental rationality are based on the idea of governing through neighbourhoods. The ENP and EaP represent the types of soft power through which the EU gently enforces the implementation of its rules and regulations beyond its territory to ensure its security. Hence ‘the ENP and EaP governmental rationalities are deeply entrenched in the Eurocentric spatial imaginaries of the EU’ (Grzymski 2018: 591). Thus, traditional matters of territorial control and sovereign border are replaced by ‘the governmentality - security dispositif’ (Vasilache 2019: 687), which can give rise to new forms of othering and division.

Within governmental logic there is ample space for biopolitical practices related to measures of controlling, managing and administering human bodies through the investment in matters affecting lives and protecting the physical existence of the population. Biopolitics places human bodies at the centre of social, cultural and political relations, shaping such concepts as nation-building, security, borders, ideology, inclusion and exclusion. In biopolitics, borders are constructed on the contingent basis of distinguishing between groups of population who are taken care of, and those whose protection is not unconditional, which ultimately sets rules of belonging and conditions of abandonment. In this regard, border biopolitics might be approached as an assemblage of medical, immigration and transportation authorities, aimed at codification of incoming groups of people, their examination and ascription to them of certain statuses (Walters 2002: 563-575). The pandemic represents a case of drastically constrained mobility and circulation of travellers across the borders (Kenwick & Simmons 2020) that play a role of biopolitical ‘filters’ (Murphy 2019: 9). Of particular importance is the idea of a ‘generalized biopolitical border’ (Vaughan-Williams 2009) mostly applied to the refugee crisis to demonstrate that the EU’s external borders not only delineate national jurisdictions but also filter out and categorise border crossers for which various biopolitical norms, rules and procedures are established. A similar approach was applied for studying ‘biometrical borders’ as an element of the war on terror (Amoore 2006). Due to the generalisability of the concept of a biopolitical border it can be extended to other cases where borders function as institutional spaces producing practices of exclusion from and inclusion in the neighbouring polities.

In the context of our analysis, these concepts play different explanatory roles. А combination of normative disagreements and geopolitical cleavages is a key driver for the crisis in EU-Russia relations that shapes policy choices of individual member states. Governmentality ought to be regarded as a set of specific policies designed by individual member states as a response to the growing complexities in the geopolitical and normative spheres. The case of Finland is particularly illustrative of the practical significance of this concept. The biopolitical elements of governmentality exacerbated by the outburst of COVID-19 is an additional factor that further complicates bilateral relations, which the case of Estonia seems to corroborate.

Some authors have discussed different contexts in which the adherence to norms might be based on a biopolitical background (Farneti 2011: 959-960). This might be illustrated by EMA’s regulations integrated into the EU's normative approaches to vaccination. Another important linkage is between governmentality and normativity: ‘If the international realm is thickening due to the institutionalization of liberal norms about human rights, market economy, democracy and the rule of law, then there seems to be a good case for subjecting the preconditions for the emergence of these norms to a governmental reading’ (Neumann and Sending 2007: 694). By the same token, the prevalence of biopolitical governmentality might be viewed as a road to post-liberalism (Chandler 2015: 12). The terminological distinctions, along with the dissimilar experiences of Finland and Estonia, only actualise the academic interest in the governmentality-normativity nexus.

A game of logics: The case of Finland

The Finnish discourse on Russia is double-edged, exemplifying a form of governmentality with a practical value for domestic purposes. A broader range of public statements, particularly in Navalny’s case, positions Finland within the European system of values. We explore how these discourses discuss Russia as an object of bilateral relation and how Russia is discursively deployed in the contexts of governmental rationalities, normative claims and geopolitical concerns.

Finland’s Russia policy is a search for a balance between expansive governmentality and normative commitments to EU solidarity implemented through technicalities of governmental practices of managing trans-border relations. The commitment to EU normativity eventually resulted in the technocratisation of Finnish-Russian cross-border cooperation, which permitted both countries to maintain border activities, and allowed switching from highly politicised issues to more practical matters of trans-border collaboration and detaching Finnish-Russian relations from antagonistic geopolitics. To illustrate that, we track the changing patterns of trans-border cooperation from its early stage of nascent governmentalisation to its current mode.

At the dawn of the post-Soviet period, prevailing trends of decentralisation encouraged Russia to strengthen its cooperation with Finnish partners. Between 1996 and 2004, Russian nascent civil society obtained substantial help from the EU-funded programmes of technical assistance – TACIS and cross-border regional development – INTERREG (Scott 2010). In the mid-2000s, the institutional mechanism of EU support for cross-border initiatives with Russia turned into different instruments of ‘pedagogical governance’ (Prozorov 2004), which sought to promote the Finnish model of civil society for border management but were limited by Russia’s capabilities (Laine 2013: 187-201). The EU-driven territorial development was traditionally based on principles of partnership, participation and a bottom-up and multi-level approach to regional governance. This sort of governmentality coincides with the neoliberal logic of differences that inclusively absorbs differential positions of local authorities, economic, cultural and social actors making them partners equally responsible for common initiative. The scale of these policies expanded dramatically within the pioneering projects in sectoral, regional and local dimensions to a great extent resembling the key characteristics of ‘good governance’ in the EU. Nevertheless, in the mid-2000s, EU projects started facing limitations due to the growing contradictions between Putin’s centralisation approach and the EU vision of cross-border governance. Political and fiscal freedoms of Russian regions were affected by Putin’s ‘vertical of power’ (Ross 2007), which later discontinued regional practices of social entrepreneurship and risk-management (Yarovoy 2010). Nevertheless, as some studies show (Belokurova 2010; Koch 2019), by shifting from explicitly democratic ambitions towards more depoliticised and technical problem-solving targets of regional management, the ENP’s financial instruments managed not only to obtain a necessary legitimation but also to support Russian-Finnish cross-border governmentality (Laine & Demidov 2012; Scott & Laine 2012).

Discrepancies between the changed centre-periphery landscape in Russia and the EU’s priorities have directly affected Finland. While the Finnish side has succeeded in using the allocated EU funds for local needs (Scott 2010) and sustaining people-to-people relations as well as civil society networks in border regions (Scott & Laine 2012), the Russian government proceeded with an imitation of grassroots activities (Demidov & Belokurova 2017), establishing a new technocratic rationale for programme implementation on the Russian territory. For instance, after the annexation of Crimea, a new set of rules was adopted for the EU programme South-East Finland-North-West Russia Cross-Border Cooperation 2014-2020, SEF–NWR CBC[2]. To receive the ‘green light’[3] for operations in Russia, this programme had to adjust to the so-called ‘foreign agent’ legislation. The changes predominantly concerned limitations in participation for Russian NGOs and prioritisation of the Moscow-driven large infrastructure projects over local initiatives. This significantly reduced opportunities for Russian third sector participants of cross-border cooperation and increased the number of state-affiliated NGOs and Moscow-based governmental agencies participating in EU programmes at the expense of local agents in Russia. Finally, there is a growing gap between Russian officials, sinking deeper into ‘bad governance’, and their European counterparts adhering to the ‘ideals and values of participatory democracy’ (Yarovoy 2021). Thus, technical governance and fast-track policy implementation were prioritised over the contribution of grassroots actions and ‘people-to-people’ activities which weakened the projects’ scope and legitimacy.

Despite all this, ‘the EU’s approach to EU-Russia civil society cooperation has not radically changed as a result of the 2014 crisis in the official relations: the existing instruments of democracy promotion were kept and adapted’ (Belokurova & Demidov 2021: 295). In fact, Finnish partners often emphasise ‘personal relationship and trust’ (Fritsch et al. 2015; Koch 2018) between Finnish municipalities and local administrations in Karelia or St. Petersburg. Moreover, the former director of Managing Authorities of the SEF–NWR CBC Tiina Jauhiainen highlighted[4] that depoliticisation of the cross-border programme is a key resilience strategy against the 2014 geopolitical complications. In this respect, EU governance created some opportunities for communication on both sides of the border. The border functioned as an area of cooperation, where relations are governmentalised, and practical issues of material background are prioritised. The centre of gravity shifted from the EU level to the technical management of two states. The dominant logic of depoliticisation in Finnish-Russian relations transforms the geopolitical conflictuality in the direction of pragmatism, supported from both sides of the border.

COVID-19: Biopolitics embedded in technocratic governance

Finland’s COVID-19 crisis management was an extrapolation of governmentality to the biopolitical functioning of the borders. The EU’s hard line stance on the non-recognition of Russia’s vaccines (Nilsen 2021) was balanced by Finnish governmental calculation and calibration of security and individual practices of risk-taking. Despite an epidemiological threat from Russia (Khinkulova 2021), the Finnish Border Guard (RAJA 2021) issued rather flexible recommendations and case-by-case assessments on border crossers arriving from third countries such as Russia.

From March–April 2021, relatives and family members were allowed to enter Finland despite the fact that Finland still kept the borders shut for non-essential trips with Estonia, which had lower infection rates and death tolls compared to Russia. In mid-July 2021, the Russian SovAvto bus-line[5] resumed regular trips from St. Petersburg to Helsinki and Lappeenranta for ‘passengers with the necessary documents and permits of the countries of departure and arrival’, while Finland kept restrictions (Finnish Government 2021) on cross-border public transport with Russia in place. Likewise, de facto exceptions were made for Finnish fans travelling to the European Football Championship in St. Petersburg, which technically contravened the official recommendations of ‘avoiding unnecessary travel to Russia’ (THL 2021) and subsequently caused a spike of corona cases in Finland (Yle 2021a).

In the official statements, Finland adhered to the EU normative rule. For instance, the question of accepting Sputnik V and its certificates in Finland was clearly relegated to EMA authority. To neutralise the biopolitical issue at stake, Foreign Minister Haavisto mentioned that Finland prefers to maintain closed borders and Corona-testing rules with all neighbours. However, in the actual biopolitical border management the Finnish authorities relied on governmentality tools that transformed the problematisation of security into a technical and pragmatic rationale of self-government, risk-taking and self-care. In such a way, technocratic governance at once fostered biopolitical operation of the border and maintained a balance between the EU rules and the Finnish border regulations regarding crossing, passing and containing the human flows. Moreover, on several occasions, Finnish parliamentarians speculated on the possibility of benefiting from the Sputnik V vaccine, putting forward the question of state-to-state procurement with Russia in case of the positive decision from the EMA.

The case of Navalny: Normativity mitigating geopolitics

The scope of the official rhetoric in the Finnish Parliament, backed by a governmental rationale, is grounded in a chain of equivalences between economic, environmental and border/neighbourhood priorities. In 2020–2021, even amid Navalny’s imprisonment, Russia was predominantly mentioned in connection to practical issues of coordinating telecommunication policies in border regions, COVID-related restrictions, Finnish export to Russia and Russian imports of raw materials to Finland. Aimed at solving technical and matters-of-fact issues, the tone of the rhetoric bore a non-political character. Russia in this respect was most commonly seen as:

1. a ‘partner’ with various connotations, i.e., economic; strategically important; potential; unreliable; difficult; unstable; and in specific areas: in the Baltic Sea; in climate change actions; in the Northern Dimension;

2. a powerful and dangerous but important neighbour that Finns know best how to deal with.

By that time, Russia was problematised in the Parliamentary debates as an object of state governance and not as a geopolitical challenger. A dislocation of conflictual meanings occurred through depoliticisation of transborder issues and a technocratic approach to the neighbourhood. The problem for Finland was how to maintain positive relations with a powerful neighbour, capitalising on geographic proximity and treating Russia as a ‘partner’. This governmental logic unfolded through productive policies of cross-border cooperation between the two neighbours. This logic supported the Finnish strategy of cultural diplomacy in building bridges between Russia and the EU, and making the Finnish position less political and more technical.

In Finland, a normative logic operates along the prevailing technocratisation and governmentalisation, mitigating geopolitical issues and providing a room for articulating them. To illustrate this, we examined a range of statements of the Finnish politicians on Navalny’s case,[6] which symbolically positioned Finland within the European value system but without far-reaching practical implications. It provided a secure space for voicing concerns over violations of human rights in Russia, while remaining in the mode of partnership with Moscow.

In January 2021, the Finnish government reacted to Navalny’s imprisonment by demanding his release. The Prime minister Sanna Marin joined the consolidated position of the Euro-Atlantic West demanding an investigation of the poisoning, and release of all arrested for peaceful protests in Navalny’s support (Yle 2021b). President Sauli Niinisto supported this claim, saying that there was ‘no ground for arrest’ (Yle 2021b). However, Niinisto did not admit the links between injustice toward Navalny and Putin’s interference in the court decision-making, referring to his unfamiliarity with Russian law, while Foreign Minister Haavisto defined this situation as a failure of democracy in Russia (which implied that Finnish foreign policy officials still think about Russia in democratic terms) (Yle 2021c).

On 15 February 2021, Haavisto met with his Russian counterpart Sergei Lavrov (Gråsten 2021) and stated that Navalny’s case is an international issue due to the decision of the Human Rights Court and the European Council. The Finnish position in this case was to protect international law and a rule-based system, of which Russia is a part. At the same time, both ministers repeated that old agreements on the Arctic and cross-border cooperation are still in place, yet each counterpart formulated it in his own way. While Lavrov reaffirmed close relations between the two countries, referring to the cooperation with pre-EU Finland, Haavisto stressed the importance of today's issues in the context of Finnish commitment to the EU and NATO policies. In a nutshell, Finland was privileged as a reliable partner in the Kremlin’s rhetoric, maintained all the established agreements with Russia on border, energy, ecology cooperation, and preferred to treat Russia as a peculiar democracy that had problems with the opposition. On the top of that, Finland was ready to continue the exchange of opinions on controversial issues, while going deeper into the negotiations on the matters that concern border and neighbourhood issues.

In this respect, sharp statements on human rights had a largely declarative character as a gesture of support for the EU's normative agenda. In practical terms, Finland was consistently committed to the strategy of building bridges between the EU and Russia through cultural diplomacy and cross-border connectivity. The vocal debate in January 2021 over the violation of human rights, which Finland traditionally stands for, did not have much to do with the actions of the Finnish government that did not pay particular attention to this issue due to more urgent matters such as COVID-19 or the EU’s ‘recovery package’. The question of ‘what do we do with Russia?’ was left to the EU level. Thus, the Finnish normativity went along with the EU value-based agenda but did not imply any radical shifts in relations with Russia after Navalny’s imprisonment. Within this approach, a series of public statements supportive of liberal values caused no serious consequences for relations with Russia.

Responding to Russia’s invasion in Ukraine

Finnish-Russian multilateral diplomacy as a ‘functional dialogue’ (Hakahuhta 2021) illustrated the prevalence of the technocratic logic of governmentality over geopolitical issues. Along with various forms of ‘depoliticization’ (Ylönen et al. 2015), this reduced geopolitical tensions in the most important areas of the Finnish economy. Unless it comes to open war, a functional dialogue with Russia continued to be a legitimate practice. For instance, after almost two months of the ‘special operation’ in Ukraine, a few Finnish researchers (Kojo & Husu 2022) became perplexed by the question of how it was even possible to continue cooperation with Russia in such a critical niche as nuclear energy, given that Finland has never recognised the legality of the annexation of Crimea. The authors exposed the shortcomings of the pragmatic approach behind ‘nuclear diplomacy’ with ROSATOM,[7] and revealed that a critical take on Russia as an ‘unreliable partner’ has been diminished by depoliticising appeals to a history of good practices, previous neighbourhood experience, cost minimisation and dismissing geopolitical risks in business and energy policy. The desire ‘to present the purchase of Russian nuclear technology . . . as an energy, economic and climate policy, without a geopolitical dimension - by keeping one's head cold and talking about energy as energy’ (Kojo & Husu 2022) seemed rational until recently.

Similar discrepancies can be observed after the 2022 restart of the war in Ukraine. Despite official statements in support of Ukraine and open assertion of actual hybrid threats emanating from Russia (Yle 2022a), including the ‘instrumentalized immigration’ (Finnish Administrative Committee 2022), Finland’s take on Russia still went along the EU rule-of-law register and did not lead to any drastic steps, such as the expulsion of Russian enterprises from Finland or the closure of borders. On 25 February Finland deprived the representatives of the Russian government of diplomatic immunity when applying for a Schengen visa, but this did not affect the rest of Russian citizens (Finnish Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2022). The Russian Embassy in Helsinki operated in a regular mode. At the end of March 2022, the Finnish state-owned railway company VR suspended passenger traffic to Russia, but not freight (Yle 2022b). And the Yangon taxi services were not banned in Helsinki the way it happened to Yandex business activities in Estonia and Latvia (Linnake 2022). When these palliative measures were called into question in the Parliament, the responsible committee typically explained that everything is in line with the common position of the EU and all the possible risks are assessed case by case (Finnish Parliament 2022a, 2022b).

By the same token, from the very beginning of the war, Finnish authorities recommended refraining from travelling to Russia (Yle 2022d), but no urgent actions against a possible spill-over of the Russian aggression were planned. In this regard, Finland still inscribed its big-brother-neighbour policy into the EU's normative standpoint toward Russia and yet relied on the principles of ‘liquid neutrality’ (Roitto & Holmila 2021) that allows for the emergence of a depoliticised space for transborder activities. Helsinki was trying to detach cross-border cooperation from geopolitical tensions, applying the logic of governmentality as a way to avoid entanglement in conflicts with Russia. This manoeuvre entailed the depoliticisation of both the administrative and cultural dimensions. For instance, the pre-war polls (Finnish Government Communications Department 2022) showed that the attitude of the Finns has significantly changed towards Russia, but not towards Russian citizens living in Finland. Therefore, Finland could strike a balance between its domestic leadership in protecting the equality and liberal rights of all its inhabitants, and complying with EU regulations regarding Russian aggression in Ukraine.

However, the all-national polls on NATO have revealed a watershed in public opinion of Finland. A record-high 62 percent of respondents supported the alliance with NATO at the end of February 2022 in the absence of an official stance from the Finnish Government (Yle 2022c). Niinistö and Marin openly announced their pro-NATO attitudes only at the parliamentary debates devoted to Finnish application to the North-Atlantic alliance at the end of March. Parliamentary hearings over Russia in February–May 2022 indicate a clear shift in tone and rhetoric: from March Russia appeared exclusively as an ‘aggressive neighbor’ and an ‘unreliable’ ex-partner, which can only be countered by a united position of the EU. Starting from this moment Finland sought to join NATO as a reaction to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, yet in the meantime still avoided boosting military confrontation elsewhere. Within this narrative, Russia was seen as an equal participant in international law, whose economic, social or cultural rights must not be violated unless they pose an acute and proven threat to Finnish society. Moreover, in the official rhetoric of the parliamentary discussions, Russia remained a neighbour that Finland has to live with, which makes Russian society a potential ‘partner’ of the future border dialogue. Apparently, previous models of technocratic governance are seen as yet capable of mitigating geopolitical conflicts and continuing pragmatic dialogue with Russia relying on the EU rule-of-law normativity.

Estonia’s trilemma

For Estonia, adherence to a common normative approach to Russia by and large overrides potential advantages of trans-border governmentality. Estonian geopolitical calculus implies European normative solidarity as a precondition for belonging to the trans-Atlantic West that secures the very independence of the country. As a flip side of this strategy, both geopolitical and biopolitical bordering became essential elements characterising Estonia’s relations with Russia. In 2021 as a – largely symbolic – gesture of securitising Russia, the Estonian government started to build a border fence. A particularly sensitive issue in this regard is the sizable Russophone population of Estonia which is often ‘treated by political elites with suspicion because of their instrumentalization by Russia, adversely affecting their prospects of integration’ (Pigman 2019: 31).

COVID-19 and the governmental rebordering

The biopolitical dimension of the functioning of Estonia's border with Russia became prominent with the outbreak of COVID-19. Two types of biopolitical bordering emerged. The first one was an effect of Estonia’s reluctance to unilaterally accept Sputnik V regardless of the preference for this vaccine among Estonian Russian speakers (TASS 2020). Some Estonian commentators opined that ‘it would be good for Estonia if Sputnik V is registered by EMA’ (Gabuev, Liik & Trenin 2021). However, joint EU-wide approaches prevailed over pragmatic considerations. Moreover, in June 2021 the Estonian health authorities identified Russia as a source of epidemiological threat and introduced additional measures of control on the border (Barsyonova 2021).

The second type of bordering was triggered by a lower scale of vaccination in the Russian speaking county of Ida-Virumaa whose population was negatively affected by the falling revenues from tourism from Russia, as well as the shrinking cross-border trade and business. These developments became an additional divisive factor for Estonia that struggles to foster the integration of local Russian speakers into the Estonian national mainstream (Wright 2021a). During the pandemic Ida-Virumaa boosted its reputation as an Estonian domestic Other and as a region that biopolitically differs from the rest of the country when it comes to vaccine scepticism. The head physician of the Narva city hospital framed the debate in biopolitical categories by saying that the major problem for fighting COVID-19 in this city is that its dwellers ‘are not afraid of death’ (Parv 2021). Some Estonian politicians and medical professionals proposed introducing special measures for the predominantly Russophone county. Being largely disconnected from Russia and treated through the lens of exceptionalism by Estonian political and medical authorities, Ida-Virumaa faced a double bordering, which challenged the policy of socio-cultural integration long pursued by the Estonian government.

Estonia’s normative standpoint

Geopolitically, Estonia’s attitudes to its eastern neighbour are to a large extent defined by Russia’s reiterative accusations toward the Baltic States of discriminating against the Russophone population (Russian Foreign Ministry 2021). In the first public explanation of the critical state of Russia-EU relations after Borrell’s visit to Russia in February 2021, Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov particularly underscored the malign, in his view, role of the Baltic States in making EU foreign policy ‘Russophobic’. This was a replica of the decades-long Russian disdain for Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian membership in the EU and NATO. The fact that the three countries were referred to in an explicitly confrontational speech meant that this Baltic trio remained an object of information attacks from Russia. Moscow did not unconditionally accept their integration with the Euro-Atlantic West, and instead kept trying to portray them as troublemakers within the EU and NATO. The mutual expulsion of diplomats from Moscow and Tallinn in February 2021, followed by the detention of the Estonian consul in St. Petersburg in July 2021, added a new element to the reciprocally alienated relations.

For Estonia, Russia is not a global player (Turovski 2021) but rather a potentially dangerous neighbour. For years, Estonia has tried to convince other EU member states that Europe needs to stay vigilant when it comes to Russia’s policy of political conditionality that treats dialogue not as a normal state of affairs but as a reward for loyalty (Rumer & Weiss 2021). As a non-permanent UN Security Council member in 2020-2021, Estonia has clearly positioned itself at the frontline of opposition to Russia's annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas. In the words of the Estonian foreign minister, ‘Russia’s aggressive foreign policy, its abandonment of voluntary international commitments and democratic values and attempts to alter the security architecture of Europe have a direct impact on the security environment around us’ (Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2021a).

However, as former President Ilves put it, Estonia does not waste time thinking of being invaded by Russia (The Agenda 2019). Being deeply integrated in EU foreign and security policy, Estonia, however, has from time to time experimented with developing its own pathways to the Kremlin. In particular, the former Estonian president Kersti Kaljulaid’s meeting with Vladimir Putin in Moscow in 2019 was an example of Estonian bilateral diplomacy rather than a policy coordinated with EU partners. In February 2021, another attempt to appeal directly to the Kremlin was undertaken; the Estonian foreign minister confirmed the interest of the Estonian government to come back to the unresolved ratification of the Border Treaty (Stoicescu 2020). On the one hand, this statement was made largely due to domestic reasons: the new government that came to power after the resignation of the former governing coalition was eager to position itself as a functional team, ready to repair the reputational losses associated with a series of controversial statements made earlier by the members of EKRE, a national populist party that was part of the tripartite governance in 2019–2021. Yet on the other hand, a return to a positive agenda in relations with Russia was announced in the beginning of the new crisis in EU-Russia relations related to the Navalny affair, and developed in parallel with the heated discussion about sanctions. The policy of developing a bilateral track in dealing with Russia found some support among the Estonian expert community: ‘should a Russian fighter jet crash over Lithuania, or a NATO one lose a missile over Estonia, it would be good for the capitals concerned to exchange information directly, as opposed to relying solely on the link between NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander Europe and the Chief of the Russian General Staff’ (Liik 2020).

However, Estonian attempts to establish a bilateral communicative liaison were rejected by Russia. As a de facto precondition for the resumption of the border treaty ratification process, the Russian Foreign Ministry referred to its concerns about the status of the Russian-language community in Estonia, along with what the Kremlin dubs ‘falsification of history’. The mainstream Russian media was assuming that Estonia would be included in the list of ‘unfriendly countries’ that the Kremlin compiled in May 2021. The initial list, however, contained only the US and Czechia, yet it was extended in 2022. As a clear sign of disdain for Estonia, Russia refused to send its delegation to the World Finno-Ugric Congress held in Tartu in June 2021, and Aeroflot has cancelled the previously resumed Moscow-Tallinn flights. Apart from that, Estonia became an object of a new type of information attack that employed deep fake technology to imitate Leonid Volkov, a close associate of Navalny, whose face image was used to trick a group of Estonian MPs (Wright 2021b).

Estonia’s normative agenda, being a key point in its foreign policy philosophy, to a large extent is the opposite to realist geopolitics which might particularise and marginalise Estonia as a small country: ‘If one can break our value base and make our cooperation only based on interests of individual countries, then we will end up exactly where we did in 1939-1940’ (Brookings Institution 2019). This standpoint was particularly exemplified by this country’s non-permanent membership in the UN Security Council. Two countries – Ukraine and Georgia – whose territorial integrity was violated by Russia were objects of special attention (Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2021b). In particular, Estonia convened a session on Crimea in the UN Security Council aimed to demonstrate an international support for human rights and discrimination of civilian populations in the Russia-occupied Ukrainian peninsula (Estonianmfa 2021). On other occasions, the Estonian foreign minister Urmas Reinsalu expressed explicit concern for Russia’s increasing military presence in Libya (Permanent Mission of Estonia to the UN 2020a) and condemned Russia’s unwillingness to cooperate on the MH17 catastrophe (Permanent Mission of Estonia to the UN 2020b). In an Estonia-convened meeting devoted to the 75th anniversary of the Second World War, Russia was accused of using the Victory Day of the 9th of May to manipulate history through the rehabilitation of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact (Permanent Mission of Estonia to the UN 2020c). In October 2020, Estonia expressed public sympathies with the Georgian government that was cyber-attacked by Russia’s military intelligence service ‘in an attempt to sow discord and disrupt the lives of ordinary Georgian people’ (Permanent Mission of Estonia to the UN 2020d). From the UN Security Council tribune, the Estonian Foreign Ministry has also condemned the assassination attempt on Alexei Navalny (Permanent Mission of Estonia to the UN 2020e).

Another aspect of normativity is solidarity within the EU. Estonia’s normative support for Czechia in expelling Russian diplomats in April 2021 became a matter of political debates that stretched beyond this specific case and extended to the matters of EU solidarity. Since the expulsion of diplomats was not an EU action, but rather a gesture of solidarity with another EU member state, this incident has further complicated the search for a balance between geopolitical factors shaping Estonia’s relations with Russia, and Estonia’s commitment to shared norms and values in its communication with the EU and its individual member states.

Estonia was definitely right in its normative conclusions about Russia as a non-democratic country detaching itself from the European values, as well as in translating these normative assessments into geopolitical by securitising Russia’s distinctions from the West. However, a major challenge for Estonia is how to transform these normative and geopolitical discourses into practices of governmentality (Liik 2020) that are mostly manifested in two domains. One is the trans-border management of water resources in Lake Peipsi and the Narva River shared with Russia. Estonia’s rotating presidency in the UN Water Convention that started in October 2021 has become possible largely to the previous record of successful implementation of a number of bilateral environmental programmes with its neighbours, including Russia (Aaslaid 2021). This example shows that even low-profile and underfunded programmes of Estonian-Russian trans-border cooperation might have a positive effect in a broader international context. Another terrain is cultural: as a combination of people-to-people diplomacy and soft power projection, Estonia is one of the most enthusiastic promoters of Finno-Ugric cooperation that includes fostering ties with kindred ethnic groups in Russia. Key target groups of this type of cultural governmentality are educators, students, scholars, artists and performers from Finno-Ugric regions of Russia whose contacts with Estonian counterparts are supported by the Estonian government through a plethora of programmes.

Estonia and Russia’s military intervention in Ukraine

From the outset of the war the Estonian government straightforwardly demanded a thorough investigation of war crimes committed by Russian troops in Ukraine (Estonian Foreign Affairs Committee 2022a) and the creation of an international tribunal for this purpose (Estonian Foreign Affairs Committee 2022b). Estonia is one of the countries in Europe that unequivocally assumed that the only option suitable for the West in this war is Russia’s defeat.[8] Estonian prime minister Kaja Kallas called Russia the only enemy of Estonia (Mikhailov 2022), due to which her government lobbied for an enhanced military presence of NATO permanent military units all across the eastern flank.[9] In the view of the Estonian president, Russia can’t be part of European security architecture.[10] Leading Estonian think tankers were highly critical of Emmanuel Macron’s conciliatory approach to the Kremlin (Raik & Arjakas 2022), and suggested that the German government should more robustly distance itself from Russia (Lawrence 2022). Estonia used different regional platforms for a better coordination of regional responses to the aggression, including the Bucharest Nine, along with regular meetings of the Foreign Affairs Committees of the parliaments of the Baltic States (2022c) and the Baltic-Nordic parliamentary sessions (Estonian Foreign Affairs Committee 2022d).

The Estonian president qualified the aggression as ‘Putin’s war, not a war of the Russian people’.[11] However, the policy of isolation and exclusion of Russia extended to the cultural sphere. The government has banned from performing in Estonia a group of Russian artists supportive of the war in Ukraine. The University of Tartu and Tallinn University refused to accept applications from Russian citizens living in Russia, and later the Estonian government discontinued the issuance of work and study visas for Russian citizens.

Russia’s intervention in Ukraine was consequential for the Estonian Russophone minority. Many local Russian speakers have publicly repudiated the aggression and expressed overt solidarity with Ukraine. In the meantime, others were unhappy with such preventive measures taken by the Estonian government as the repeal of gun licenses from non-citizens, the ban on public demonstration of war-supportive symbols, deportation to Russia war supporters and ubiquitous exposure of Ukrainian flags.

The policy of rebordering pursued towards Russia is in sharp contrast to a drastic debordering of Estonia’s relations with Ukraine, a country that became, in the eyes of the Estonian government (2017), central for Euro-Atlantic security. Estonia was one of the first countries that immediately after the commencement of the war raised the issue of granting a candidate status to Ukraine (Estonian Foreign Affairs Committee 2022e). The Estonian Parliament called on speeding up the delivery of military aid to the Ukrainian Armed Forces, increasing financial support to Ukraine and to neighbouring countries hosting the war refugees, as well as planning for the long-term reconstruction of Ukraine (Estonian Foreign Affairs Committee 2022f).

Conclusion

In the concluding section we dwell upon three major points. First, our research has shown the analytical value of the three logics for explaining the three crises that shape EU-Russia relations. The three critical junctures reveal that Finland’s and Estonia’s policies are conditioned by different combinations of these logics. When it comes to COVID-19, the EU’s reaction was shaped by a mix of biopolitical and governmental logics; in response, Russia geopoliticised the EU’s stand by accusing the EU authorities of intentionally blocking the access of Sputnik V into the European markets. The drastic deterioration of bilateral ties since January 2021 was driven by the collision of EU’s normative approach to the Navalny affair and Russian reaction that ascribed to Brussels’ geopolitical motivations, (mis)interpreting EU’s normativity as an interference into Russian domestic affairs.

Second, the three logics are instrumental for shedding light on different types of actorship in times of crises. The distinct yet simultaneous logics of geopolitics, normativity and governmentality configure a range of policy options of EU member states towards Russia. The two compared countries in consideration significantly differ from each other in this regard (Table 1).

Table 1. Unfolding the logics in Finland and Estonia

|

Logics/countries |

Finland |

Estonia |

|

Geopolitics |

Acceptance of Russia’s power and cooperative relations with Moscow as a recipe for Finland’s security |

Membership in the EU and NATO as security warranty |

|

Normativity |

Support of EU sanctions against Putin’s regime and centrality of human rights and humanitarian issues in foreign policy agenda |

Normative solidarity of the trans-Atlantic West and accentuation of value-based distinctions between democracies and non-democracies |

|

Governmentality |

Technical approach to cross-border management, depoliticization of the EMA/EU approach |

Environmental and cultural diplomacy, accompanied by biopolitical othering of Russia that affects local Russophones |

Source: authors

The prevailing logic of governmentality secures Finland’s commitments to normativity. In this regard, the predominantly depoliticised cross-border relations may reconcile the contradiction between the priorities of member states and their commitments to the EU consensus. Finland’s Russia policy is seeking a balance between normative commitments to EU solidarity and practical governmentality. More precisely, normativity is implemented through technicalities of governmental practices of managing trans-border relations. Normative politicisation and governmental depoliticisation are the two sides of the Finnish official thinking.

In the case of Estonia, normativity overlaps with and is affected by a geopolitical agenda that enhances the country’s sovereignty through its association with the EU normative power and the concomitant bordering of Russia. Estonia’s Russia policies are to a much greater extent embedded in normative approaches that, however, are adjusted to the other logics. Estonian geopolitical calculus considers European normative solidarity as a precondition for belonging to the Euro-Atlantic West that secures the independence of the country. As a flip side of this strategy, both geopolitical and biopolitical bordering became essential elements characterising Estonia’s relations with Russia. Estonia’s adherence to common regulations of vaccine registration was a good illustration of a balance between biopolitical and normative frames of reference. The geopolitical rationality made Estonia heavily rely on NATO military support as the cornerstone of national security, while avoiding closing down the bilateral track of communication with Moscow. By the same token, Estonia practiced governmentality through maintaining cultural relations with Russian Finno-Ugric communities and developing low-profile cross-border programmes.

Both Tallinn and Helsinki express solidarity with the EU position on Russia in respect of political freedoms, COVID-19 policies and the rule of law. However, Finnish-Russian relations can be mapped at the intersection of EU normativity and practical governance, while Estonia places a stronger emphasis on blending normative power with geopolitical mechanisms of protecting the national territory. For Finland, mundane issues of direct relevance to the border communication facilities, economic growth, territorial security, and water and land pollution define the content of technical management between the neighbours. While for Estonia major concerns are measures of border security, including its military dimension.

Our study confirms that each of the three logics/rationalities is a matter of divergent interpretations not only between Russia and the EU but also between individual member states. Estonia understands the normative position as a prevalence of a common EU-wide values-based solidarity over economic gains, while Finland finds a balance between commitment to joint rules of dealing with Russia and depoliticised trans-border cooperation. The geopolitical frame of action for Estonia implies deep integration with transatlantic security infrastructure, while for Finland it is based on good-neighbour relations that, of course, need to be readjusted to Finland’s NATO membership. The Finnish model of governmentality is less topical for Estonia due to a high level of securitisation of bilateral relations with Russia. In biopolitical regards, both Finland and Estonia have adequately assessed epidemiological threats coming from Russia, and adhered to the regulations provided by EMA.

One more inference from our analysis, partly supported by previous research (Raik et al. 2015), concerns important distinctions regarding connections and disconnections between the logics as put into practice by the two countries. Estonian foreign policy implies two clearly articulated linkages – between normativity and geopolitics (the values-centric security perspective), and between normative approaches and biopolitics (adherence to common policies under the auspices of EMA). In the meantime, Estonia delinks normativity as a collective frame of EU’s policy towards Russia from ‘islands’ of trans-border governmentality that are in the hands of member states. Similarly, Estonia disconnects biopolitics as a sphere of technical policies from more politicised and confrontational geopolitics.

In the case of the Finnish foreign policy the picture appears different. Like Estonia, Finland looks at biopolitics from a normative angle adhering to the principle of EU solidarity, yet – unlike Estonia – puts a premium on liaising normative power and the force of governmentality. As for disconnections, Finland’s government sees normative pronouncements towards Russia detached from and unrelated to the domain of governmentality, and is not supportive of geopoliticisation of the coronavirus crisis. The different instrumentalisation of the three logics is a powerful explanatory factor that might shed more light on distinct policies of EU member states towards Russia beyond the two countries researched in this article.

***

Funding

Tatiana Romashko’s contribution to this article was supported by the Kone Foundation (Koneen Säätiö), grant number 87-47404.

Andrey Makarychev is professor of regional political studies at the University of Tartu Johan Skytte Institute of Political Studies. He teaches courses on ‘Globalization’, ‘Political Systems in post-Soviet Space’, ‘EU-Russia Relations’, ‘Regional Integration in post-Soviet Space’, ‘Visual Politics’ and ‘The Essentials of Biopolitics’. He is the author of Popular Biopolitics and Populism at Europe’s Eastern Margins (Brill, 2022), and co-authored three monographs: Celebrating Borderlands in a Wider Europe: Nations and Identities in Ukraine, Georgia and Estonia (Nomos, 2016), Lotman's Cultural Semiotics and the Political (Rowman and Littlefield, 2017) and Critical Biopolitics of the Post-Soviet: from Populations to Nations (Lexington Books, 2020). He has co-edited a number of academic volumes: Mega Events in post-Soviet Eurasia: Shifting Borderlines of Inclusion and Exclusion (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), Vocabularies of International Relations after the Crisis in Ukraine (Routledge, 2017); Borders in the Baltic Sea Region: Suturing the Ruptures (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017). His articles have been published in such academic journals as Geopolitics, Problems of Post-Communism, East European Politics and Societies, European Urban and Regional Studies, among others.

Tatiana Romashko is a grant researcher and PhD candidate at the Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Her research interests include Finnish-Russian cross-border cooperation, Russian politics and cultural policy. Tatiana is currently finishing her dissertation on the emergence of state cultural policy in modern Russia. The main results of her doctoral research have been published as journal articles (in Russian Politics) and book chapters. In 2023-2026, Tatiana Romashko will work on the project ‘Russian World’ Next Door: discourses of Russian political communication and cultural diplomacy in Finland, supported by the Kone Foundation.

References

Aaslaid, A. (2021): Estonia is Organizing a Significant Meeting on Transboundary Watercourses. Ministry of Environment of Republic of Estonia, 29 September, <accessed online: https://envir.ee/en/news/estonia-organising-significant-meeting-transboundary-watercourses>.

Ahrens, B. (2018): Normative power Europe in crisis? Understanding the productive role of Ambiguity for the EU’s Transformative Agenda. Asia Europe Journal, 6, 199–212.

Amoore, L. (2006): Biometric Borders: Governing Mobilities in the War on Terror. Political Geography, 25, 36-351.

Baar van, H. (2017): Evictability and the Biopolitical Bordering of Europe. Antipode, 49 (1), 212–230.

Barsyonova, N. (2021): Kadri Liik: strany Baltii v Otnoshenii Rossii Mogli by Deistvovat Vmeste s ES i NATO [Kadri Liik: The Baltic States Could Act Together with the EU and NATO on Russia]. ERR, 24 April, <accessed online: https://rus.err.ee/1608189115>.

Baunov, A. (2021): The Pandemic Has Failed to Unite Russia and Europe. Moscow Carnegie Centre, 27 January, <accessed online: https://carnegie.ru/commentary/83741?fbclid=IwAR3m46eQUrfujJHPmU1VqE0cge9-0hMVQhN9hph9mD0dod_zNorVURXLcI8>.

Belokurova, E. (2010): Civil Society Discourses in Russia: The Influence of the European Union and the Role of EU–Russia Cooperation. Journal of European Integration, 32(5), 457-474.

Belokurova, E. & Demidov, A. (2021): Civil Society in EU-Russia Relations. In: Romanova, T. & Maxine, D. (eds.): The Routledge Handbook of EU-Russia Relations. New-York, Routledge, 289-299.

Brookings Institution (2019): Estonia in an Evolving Europe. YouTube, 13 March, <accessed online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8gylx-ZmNo4>.

Casier, T. (2018): The Different Faces of Power in European Union–Russia Relations. Cooperation and Conflict, 53(1), 101–117.

Chandler, D. (2015): Postliberalism as an International Governmentality. Journal of International Relations and Development, 18, 1-24.

Dean, M. (2010): Governmentality: Power and Rule in Modern Society. London: Sage.

Diez, T., Manners, I. & Whitman, R. G. (2011): The Changing Nature of International Institutions in Europe: The Challenge of the European Union. European Integration, 33(2), 117-138.

Estonian Government (2017): Ratas: Ukraine’s Future will determine European security architecture in the coming decade. Republic of Estonia Government, 6 April, <accessed online: https://valitsus.ee/en/news/ratas-ukraines-future-will-determine-european-security-architecture-coming-decades>.

Estonian Foreign Affairs Committee (2022a): Mihkelson: All War Crimes Must Be Punished. Foreign Affairs Committee, April 6. <accessed online: https://www.riigikogu.ee/en/press-releases/foreign-affairs-committee-en/mihkelson-all-war-crimes-must-be-punished/>.

Estonian Foreign Affairs Committee (2022b): Statement by Foreign Affairs Committee Chairs of National Parliaments Calling for the Creation of an International Criminal Tribunal. The Parliament of Estonia, 7 March, <accessed online: https://www.riigikogu.ee/en/press-releases/foreign-affairs-committee-en/statement-by-foreign-affairs-committee-chairs-of-national-parliaments-calling-for-the-creation-of-an-international-criminal-tribunal/>.

Estonian Foreign Affairs Committee (2022c): Share Print Baltic Foreign Affairs Committees Discuss Strengthening Security of the region in Lithuania. The Parliament of Estonia, 10 June, <accessed online: https://www.riigikogu.ee/en/press-releases/foreign-affairs-committee-en/baltic-foreign-affairs-committees-discuss-strengthening-security-of-the-region-in-lithuania/>.

Estonian Foreign Affairs Committee (2022d): Share Print Meeting of Nordic and Baltic Chairs of Foreign Affairs Committees Focuses on Russia’s Aggression in Ukraine. The Parliament of Estonia, 4 April, <accessed online: https://www.riigikogu.ee/en/press-releases/foreign-affairs-committee-en/meeting-of-nordic-and-baltic-chairs-of-foreign-affairs-committees-focuses-on-russias-aggression-in-ukraine/>.

Estonian Foreign Affairs Committee (2022e): Marko Mihkelson: It Is Time to Grant Ukraine the Status of a Candidate Country for the EU. The Parliament of Estonia, 25 February, <accessed online: https://www.riigikogu.ee/en/press-releases/national-defence-committee-en/marko-mihkelson-it-is-time-to-grant-ukraine-the-status-of-a-candidate-country-for-the-eu/>.

Estonian Foreign Affairs Committee (2022f): Chairs of the Parliamentary Foreign Affairs Committees of Northern Europe Call on Increasing Support to Ukraine. The Parliament of Estonia, 17 June, <accessed online: https://www.riigikogu.ee/en/press-releases/foreign-affairs-committee-en/chairs-of-the-parliamentary-foreign-affairs-committees-of-northern-europe-call-on-increasing-support-to-ukraine/>.

Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2021a): Report. Republic of Estonia Government, 16 February, <accessed online: https://vm.ee/en/news/report-foreign-policy-minister-foreign-affairs-eva-maria-liimets-parliament-estonia>.

Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2021b): Estonia in the UN Security Council. Republic of Estonia Government, June, accessed online: https://vm.ee/en/activities-objectives/estonia-united-nations/estonia-un-security-council.

Estonianmfa/YouTube channel of the Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2021): Crimea: 7 years of Violations of Ukraine’s Sovereignty and Territorial Integrity in 2013. YouTube, 21 March, <accessed online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f2kk9qM1jbo>.

Farneti, R. (2011): The Immunitary Turn in Current Talk on Biopolitics: On Roberto Esposito’s Bios. Philosophy and Social Criticism, 37 (8), 955-962.

Finnish Administrative Committee (2022): Valiokunnan Mietintö HaVM 16/2022 vp HE 94/2022 vp [Committee Report HaVM 16 /2022 vp HE 94/2022 vp]. The Finnish Government, 21 September, <accessed online: https://www.eduskunta.fi/FI/vaski/Mietinto/Sivut/HaVM_16+2022.aspx>.

Finnish Government (2021): Restrictions During the Coronavirus Epidemic. The Finnish Government, 26 July, <accessed online: https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/information-on-coronavirus/current-restrictions>.

Finnish Government Communications Department (2022): Behavioural Study: Preparedness, Community Spirit and Clear Operational Recommendations Improve Finns' Ability to Deal with Crises. The Finnish Government, 12 April, <accessed online: https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/-/10616/behavioural-study-preparedness-community-spirit-and-clear-operational-recommendations-improve-finns-ability-to-deal-with-crises>.