Abstract

This paper combines anthropological and other critical security studies with research on cultural work to better understand the impact cultural institutions may have on the (de)securitisation of minority groups. Today minority issues represent a recurrent theme in various national and European contexts. Often perceived as a threat to social cohesion and linked to multiple successive crises, minorities and migrants have been the focus of security measures at different times. This paper focuses on the EU-funded project ‘Agents of Change: Mediating Minorities’ and explores how cultural work aimed at diversity and inclusion interacts with the dynamics of securitisation. Zooming in and out between the project goals and definitions, mundane local practices, institutional work and the broader (trans)national contexts, this paper discusses its intervening effects while also acknowledging numerous contradictions that make any straightforward narrative of minority desecuritisation difficult. With the help of empirical examples, this paper demonstrates a way to widen research beyond typical securitising and securitised actors and it contributes to a more nuanced understanding of the contexts of securitisation. Although the countermoves initiated by cultural work are never guaranteed to succeed, studying them opens new pathways to reflect upon the ambiguity of (de)securitisation as an open-ended process involving different actors, power relations and operating at multiple interdependent scales. These countermoves also indicate the shifts taking place in the current ways of thinking about and approaching minorities, challenging dominant constructions driving securitisation.

Keywords

Introduction

In the past decades multiple successive crises of public order, national identity, health and global relations have clearly skewed the uneasy balance between two competing discourses about justice and security. Despite efforts to create a more fair and inclusive society, a focus on threats from a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural composition of states has become prevalent in everyday discourses. This perspective influences social relations, urban development and state institutions, constantly conflating new securitised needs and concerns. But more than anything else this affects negatively minority and migrant communities, frequently portrayed by the states as centres of political uncertainty and insecurity for the majority population.

The role of minorities in shaping crisis-ridden perceptions and narratives has been widely discussed before (Al & Byrd 2018; Jaskulowski 2017; Innes 2015). Since the 1990s, the increased political interest in questions around minorities and their integration into societies has occurred alongside a shift in security priorities, with emphasis moving from geopolitical to biopolitical concerns, that is focusing on the population and its collective resilience against the undesired Others (Duffield 2005). This emphasis on human differences as a problem consequently leads to increased vilification of minorities and migrants in various spaces and times, while extraordinary circumstances, such as most recently the COVID-19 pandemic, ‘tip the scales’ and pave the ground for their securitisation in institutions and among citizens (Carlà & Djolai 2022: 122).

To date, much scholarly attention has been devoted to studying state securitisation practices, including how political elites perform security and the ways in which people experience these practices in their daily lives. In this paper, however, I look sideways at the intermediary social agents and examine the intervening practices of cultural organisations within the dynamics of securitisation. Although cultural organisations are rarely the focus of security studies, they are a part of wider ‘societal, political, and cultural networks of interdependencies which are directly involved in the emergence and the changing balances of power’ (Langenohl 2019: 51). They can thus provide new insights into minority securitisation, particularly how certain discourses and practices become entrenched or challenged. I acknowledge that the term ‘minority’ is a fluid, contingent signifier, neither an entity nor a specific social or ethnic category. However, for the analytical purposes of this paper, I focus on two etic designations applied to people from outside the community: the old or national minorities and the new minorities, often referred to as immigrants (see Malloy 2013). This is done to better understand the socio-political landscape and the narratives that the cultural project and institutions I studied were working against.

My perspective on securitisation is informed by critical approaches in anthropology and IR, where securitisation is predominantly seen as an ambiguous and open-ended process. This processual and performative nature highlights the simultaneity of moves and countermoves and is crucial for our understanding of how changes in hegemonic discourses arise, are challenged or come to a halt at multiple scales, ranging from global to the interpersonal. Based on this, I investigate how cultural work solutions to diversity and inclusion interact with the (de)securitisation process, providing insights into its dynamics. I focus on the subversive practices of the transnational project ‘Agents of Change: Mediating Minorities’ (MeM).[1] The project (2020–2022), which was developed by partner institutions in Estonia, Latvia, Finland and Sweden, received financial support from the Creative Europe programme and aimed to promote cultural diversity and social inclusion of minorities through art mediation.

In the past, programmes aimed at improving the social inclusion of minority populations have been criticised for being ‘little more than token measures’ (Kóczé 2019: 186) or even contributing to further societal marginalisation and securitisation. However, by examining the strategic function of MeM through a scalar perspective – that is, looking at what the programme stated, what it did, how it was adopted by the partner institutions and its impact in specific socio-political contexts – I provide evidence of the project’s potential to transform hegemonic social discourses about security. I demonstrate how alternative approaches to minorities, power-sharing and audience engagement fostered within the project helped to include marginalised voices and cultivate spaces for dialogue. They also raised awareness of obstacles, strengthening local communities’ capacities to critically reflect on dominant discourses and creating possibilities for future social change. At the same time, zooming in on two participating institutions, the Russian Museum in Estonia and the Cultura Foundation in Finland, and their local work with Russian-speaking minorities, I highlight several contradictions, grounded in institutional differences, divergent viewpoints or broader national discourses, which presented challenges to the project's transformative visions. As this paper therefore argues, with the emergence of countermoves, the old language of security does not simply fade away but enters a field of tension between competing ways of thinking and speaking about minorities. This tension gradually transforms, taking new meanings over time.

To analyse the MeM project, its local and wider impacts, I first delve into the notion of ‘stranger making’, as discussed by Sarah Ahmed (2000, 2012). I aim to elaborate on the process through which minorities become securitised and why challenging the existing notions of threats can be a difficult task. The following section then combines the research on cultural work with studies on securitisation and, with help of an empirical discussion, seeks to offer a more nuanced approach to (de)securitisation, moving beyond a one-dimensional interpretation and towards a non-binary framework that takes into account multiple actors, practices and contexts at play.

‘Stranger making’ or how minorities become securitised

The post-Cold-War era has seen a significant change in the focus of security concerns. New violent conflicts, changes in population movements and reshuffling existing populations set the stage for current security policies and expanded the concept of security beyond the territorialised national states to include the protection of basic human needs – survival, development, freedom and identity (Wæver 1995). Some scholars argue, however, that this new framework for security has been problematically driven by a zero-sum mentality (van Baar et al. 2019; Bourbeau 2011; Langenohl & Kreide 2019). It is used to reproduce, intentionally or sometimes unintentionally, forms of non-belonging while portraying certain communities as potentially threatening and on this basis excluding them from access to territories, citizenship, public services and human rights at large. As a result, the formation of security may not necessarily lead to a more secure world, but instead perpetuates insecurity and precarity for certain groups, particularly minorities and migrants (van Baar et al. 2019: 2).

The idea that minorities and migrant populations might pose a threat to the existence of a fragile nation has long been a prevalent societal issue (Canetti-Nisim et al. 2008; Djolai 2021; Duffield 2005; Malloy 2013). Throughout history, different minority groups were envisioned as disloyal, prone to conflict and secessionism, and at times they were seen as a ‘fifth column’ that causes anxieties and apprehension (Pedersen & Holbraad 2013). Today, media and political discourse on migration and integration often highlight the deficits and socio-structural problems of immigrant minorities, producing distorted images of their criminal behaviour, religious radicalism, ethnic isolation as well as lack of integration into the ‘receiving societies’. Only rarely are minorities seen as crucial social actors, while their supposed socio-political and cultural differences are depicted as a potential source of destabilisation in need of discipline through assimilation and securitised responses, such as enhanced surveillance and coercion (see Glick-Schiller & Faist 2009: 4; Demossier 2014; Smith & Holmes 2014 for discussion).

As Jef Huysmans rightfully remarks (2019: vi), the question is not whether minorities and migrants are objectively threatening to the nation-state, but rather why they are perceived a security issue and by whom. By drawing attention to security practices and their involvement in the production of insecurities, he argues, it is possible to shift responsibility for security policy consequences ‘to those claiming to defend and protect’ (ibid.). Following this line, several scholars note how subjectification and categorisation of certain people as threatening ‘strangers’ within the framework of security is always contingent upon specific material, historical and socio-economic conditions (Ahmed 2000; Maguire et al. 2014). To understand then why minorities continue to be posed as threats we must consider the dominant political regimes within which minorities live and which continue to divide the world into the nation states (Apostolov 2018: 9).

Despite globalised developments and the movement of people, old ideas of territorially fixed communities and stable, localised cultures still dominate Western thought and politics about nations (Demossier 2014: 27; Jutila 2006; Malkki 1992). Such cultural fundamentalism and essentialism are grounded in the idea that cultures are internally homogenous – they are ‘gardens separated by boundary-maintaining values’ (Malkki 1992: 28). This perspective creates essentially antagonistic relationships between groups, further tainted by colonialism and racism (Kóczé 2019), situated in the ‘nesting orientalisms’ (Bakić-Hayden 1995) and Euro-centrism (Mignolo 2014), incentivising some countries to reassert their own ‘Europeanness’ at the expense of undesired Others and undesired pasts. Although rigid national imaginaries have been frequently contested, in the face of exceptional events and crisis they become ‘powerful tropes of national reification’ (Demossier 2014: 28), whereas immigrant minorities become ‘foils’ against which nation-states come to assert their own identity and ontological existence (Feldman 2005: 238).

In this context, attempts to rehabilitate nation-state sovereignty against other groups of people could be regarded as securitising moves (Browning 2017; Feldman 2005). The process of securitisation then occurs by fostering an insider-outsider distinction and by delimiting a potentially threatening group as requiring ‘emergency measures’ (Buzan et al. 1998: 24; Carlà & Djolai 2022). In that sense, the ‘quest for homogeneity as a form of safety’ (Djolai 2021: 3) always securitises; by ordering and othering it necessarily brings more insecurities into the world (Huysmans 2006, 2014). One dramatic effect of such ontological securitisation, as Christopher Browning (2017: 50) observers, is that it places minorities ‘in the almost impossible position of constantly having to prove their belonging’, while remaining subject to particular levels of scrutiny and the assimilationist tendencies. The ordering principle through which securitisation takes place fosters furthermore alienation and aggravates access to resources and freedoms in the society at large.

The academic literature on the daily lives of migrants and minorities often perpetuates this ‘language of difference’ and reinforces national identities and borders (see Çağlar & Glick-Schiller 2018: 12 for critique). Surprisingly, this occurs alongside the emergence of voluminous ethnographic and historical work that aims to challenge homogenous portrayals of individuals as having only one identity, one country and culture. Nina Glick-Schiller and Ayse Çağlar (2016), for example, argue that even when scholars stress multiple intersecting and fluid identities of people, they do not necessarily challenge the notion of the ‘foreigner’ as separate from the ‘majority’ or ‘natives’ in a nation-state. In fact, the emphasis on difference, even in a positive sense, only reinforces – albeit unwittingly – images of people as belonging to distinctive communities divided in terms of backgrounds, aspirations and values.

All these different layers – medial, political, academic – necessarily feed securitisation, explaining consequently why it is so tempting to securitise minorities and so difficult to challenge the stranger figure who always lurks as a potential threat. In this light, some authors argue that it is logically impossible to desecuritise minority rights and to move security issues back into the ordinary public sphere of discussion (Roe 2004). At the same time, the spectrum of possibility for transformative action, and its visibility, depends increasingly on the approach to securitisation one takes. Instead of assuming coherence of securitisation, below I discuss its ever changing relational landscape which could open up prospects for change in the precarious situation of the marginalised groups.

(De)securitisation through cultural work

Drawing from literatures on the anthropology of security (Glück & Low 2017; Goldstein 2010; Maguire et al. 2014; van Baar et al. 2019) and other critical approaches (Huysmans 2014; Langenohl & Kreide 2019), this article raises questions about the possibility for desecuritisation to occur (see also Donnelly 2015; Dimari 2021; Fridolfsson & Elander 2021; Skleparis 2017). In other words, I seek to explore whether and how discussing security questions and issues in relation to minorities could be made possible ‘without reifying them as existential dangers’ (Huyusmans 2006: 127).

To date different views of securitisation exist and could be broadly delineated into two frameworks. The Copenhagen School emphasises, for example, the power of the ‘speech acts’, arguing that by calling to secure against insecurities actors (i.e. political leaders, governments, lobbyists) undertake a ‘securitising move’, whereas successful securitisation depends on an audience’s readiness to endorse these security utterances (Buzan et al. 1998). Others, whom Faye Donnelly (2017) terms as ‘second-generation scholars’, work primarily with the so-called sociological approach, which refers to securitisation in terms of practices, context and power relations that define the construction of threat images (Balzacq 2011). Both frameworks should not be seen as mutually exclusive and when taken together point to a more complex understanding of securitisation as fractured and multifaceted ‘regimes of practices’ (Fridolfsson & Elander 2021: 41). Such an approach to securitisation is built upon the understanding that security itself is not a straightforward modality of constructing enemies but rather ‘a site of social struggles in and through which power relations are continually enforced, contested and in need of being produced and re-produced’ (Glück & Low 2017: 287). It introduces then a space for contestation or desecuritising moves to occur.

Unlike securitisation, relatively little is known about desecuritisation, especially how it unfolds in practice (Donnelly 2015). Across security studies, desecuritisation has often been viewed as a ‘conceptual twin to securitisation’, its positive supplement that can follow after (Hansen 2012: 526; Austin & Beaulieu-Brossard 2018). In very basic terms, as described by the Copenhagen School, desecuritisation involves a return from an emergency mode to the area of normal political negotiations which occurs in the absence of security speech acts (Buzan et al. 1998: 4). In contrast, others highlight relational simultaneity of two processes (Austin & Beaulieu-Brossard 2018; Djolai 2021). Donnelly (2017: 250), for example, usefully suggests seeing securitisation as a ‘game’ defined by moves and countermoves, and structured by divergent viewpoints, silences and emotions. As it is a game, ‘the beginning and ending of (de)securitization processes are not clear-cut; instead, such processes can unfold without a fixed script, sound or rhythm’ (Donnelly 2017: 251). The intricate nature of (de)securitisation is thus the result of complex social interactions that are formed and informed by discourses and practices of ordinary citizens, social organisations and the political institutions (Demossier 2014: 39).

In this article, I draw on this understanding and suggest that a more nuanced analysis of countermoves is still necessary to understand how the disabling boundaries could be implicitly offset or explicitly challenged. Since countermoves can take different shapes and forms, ‘some of which fall outside our current understanding of what security means and does’ (Donnelly 2015: 926), a more ‘sideways’ approach is necessary (van Baar et al. 2019). By sideways I understand practices which are not intrinsically seen as security practices or were not intended to be such, but which become political ‘by adopting or resisting normalised discourses and practices of security’ (Zembylas 2020: 5). Approaching (de)securitisation sideways could help uncover connections between security and other social issues, leading towards a more complex understanding of how exclusions are negotiated more generally.

Taking this sideways approach, I concentrate on cultural institutions and projects, which David Carr (2003: 1) regards as ‘a mind producing system’, but which only rarely make the focus of security studies. The dominant interest is still on state measures, authorised persons and institutions as well as their discursive acts, with growing attention to the effects of the policies on human lives more recently. Meanwhile, cultural institutions constitute a dominant part of our cultural landscape, they frame our most basic assumptions about the past, the present and about ourselves. As booming research on cultural work demonstrates, they are vital socio-spatial spheres where discourses and practices meet and clash (Cohen 2015; Comunian & England 2020).

When we think about social change that cultural work might pursue we must be critically aware of the complex background of expectations, institutional interdependencies as well as asymmetrical relationships that define the lives of cultural institutions and their individual workers. Often seen as beacons of diversity that could potentially undermine the settled understanding of difference as a threat, cultural institutions are themselves not neutral: they are sites of forgetfulness, fantasy, and a particular gaze that could often lead to further marginalisation of different minorities. While examining museological work, Richard Sandell (1998), for example, demonstrates how cultural institutions are involved in institutionalised exclusions. They operate a host of mechanisms which may serve to hinder or prevent access to their services by a range of groups. They are furthermore confined in the subjectivities of their own workers, who are key agents in interpreting, using and understanding wide-ranging policy expectations towards inclusivity (McCall & Gray 2013). This often leads to a valid critique that cultural institutions can hardly serve as active sights of resistance to hegemonic and often exclusionary discourses (Kassim 2018). In the article tellingly titled ‘Good for you, but I don’t care’, Bernadette Lynch (2016: 258) thus deems practices of cultural institutions as ‘shallow political gestures’ that by trying to promote ‘empowerment-lite’ actually disempower people and overlook racism and other inequalities.

At the same time, cultural institutions too experience exclusions shaped by internal dynamics and the laws of its labour market. They are expected to rework global inequalities in times when the precarious nature of creative and cultural work remains largely invisible in the eyes of policy makers (Comunian & England 2020). Unstable working conditions (i.e. temporary work, freelancing), low earnings, excessive working hours as well as the fragmented and individualised nature of the work have resulted in precarious livelihoods to the extent that the majority of creative and cultural workers constitute now ‘the middle-class working poor’ (Krätke 2011: 144). These experiences underscore the ambivalence of chances for transformative acts, while the process of going against the current of established exclusionary visions remains interwoven with practices of securitisation (van Baar et al. 2019: 5). This leads sometimes to perceptions of cultural work as a one-man or, by extension, one-project struggle which does not always bring the desirable change.

It is against this background that the empirical section sets out to analyse the work of the international cultural project and participating institutions in their attempt to reframe previous exclusionary understandings about minorities. Arguably, the case offers ample opportunities to reflect upon different ways through which cultural work on diversity and inclusivity interact with the (de)securitisation process, affording more insights into the specific dynamics through which it unfolds.

Methodology

The data for this article derives from a two-year ethnographic study of the international cultural project, MeM, between October 2020 and 2022. MeM was a multi-layered project that consisted of five cultural and civic society organisations, their representatives and forty mediation volunteers (ten in each country). The organisations included the Foundation for an Open Society Dots and the Centre for Contemporary Art (LCCA) in Latvia, Tensta Konsthall in Sweden, Tallinn City Museum/Russian Museum Branch from Estonia and the Cultura Foundation in Finland. According to the project description, the main goal was to enhance the inclusion of underrepresented groups by involving them in dialogue with art and cultural institutions through an innovative art mediation approach.

The MeM mediation programme was a unique and innovative model that constantly adapted to the needs of the participants and contexts. This flexibility resulted in a more locally-based understandings of the excluded communities and approaches to them. For example, the Finnish and Estonian teams worked with Russian-speaking populations, whose presence is often linked with the potential for conflict, while the Swedish team focused on the declining public space in the underprivileged area of Tensta. In Latvia, the programme centred on the topic of dementia that affects the ageing population society but is often ignored. These different approaches reflected the broader calls within the cultural sector to work ‘with’ people, rather than ‘for’ or ‘on behalf of’ them (Lynch 2016: 255).

Through the focus on MeM, the current study aims to broaden the perspectives on securitisation by examining the intervening practices of social and cultural parties beyond the typical securitising and securitised actors. Methodologically, it was designed to map the production of alternative narratives about minorities, analysing how these narratives were constituted within the project, how they were transmitted across different scales and what impact they had. To understand MeM’s indirect involvement in the (de)securitisation process, a scalar gaze was adopted (Fraser 2005; Green 2005), which looked at the relationships between different agents (their personal and social identities), practices (discursive and non-discursive) and contexts (local, national and global) while employing different methods of data collection (Balzacq 2011). The detailed dataset is presented in Table 1, and in this article, I offer an overview of the practices within the project and the two local partners – Estonia and Finland – that I followed in more detail, drawing mostly from observational notes, interview data and questionnaires.[2]

By combining different layers of analysis, I address recent criticisms of the discursive bias in securitisation studies, which often overlook the affective, social and political complexities of the process by prioritising ‘speech acts’ alone (Färber 2018; Zembylas 2020). In contrast, I explore how the narratives and practices within MeM are contextually situated. Specifically, the empirical sections below describe three interrelated strategies that could be broadly considered as MeM’s counter interventions: (i) attempts to rearticulate the local meanings of minority by appealing to global discourses on diversity; (ii) contestation of established power dynamics through inclusion; (iii) and a rethinking of the importance of audiences and their emotions. These strategies, I argue, are socially transformative as they provide space for marginalised voices, facilitate dialogue and exchange, and uncover difference in experiences. Yet, while they seem successful on the surface, they encounter conflicting interests and values in the contested national and institutional landscapes. The discussion that follows is therefore not about a straightforward desecuritisation, but rather reflects the ambiguity of the (de)securitisation process and its open-ended and contested nature.

Table 1: Overview of the Dataset

|

Types of Data |

Details |

|

Interviews |

10 with representatives of partner organisations around their individual backgrounds, their perception of the institutions they work for, personal involvement with the current project, hopes and potential difficulties. 11 with project volunteers/mediators about their backgrounds, the motives for joining MeM, and their opinion about international and local dynamics. |

|

Surveys (conducted by project evaluator Sadjad Shokoohi). |

26 baseline and 20 final with volunteers/mediators about conceptual understandings, experiences & perceptions of diversity, inclusion/exclusion. 15 with partner institutions about the key project terms. |

|

Focus Group |

1 with representatives of partner organisations. The partners were asked to reflect back on their past projects, organisational policies and practices of diversity, make-up of organisations and ways of reaching out to the audiences. |

|

Observations from partner meetings |

20 hours |

|

Observations from international educational programme meetings |

16 hours |

Source: The author

Cultural institutions, counterstrategies and social change

Rearticulating the notion of minority

In one of our initial conversations, Daria, the curator of MeM’s educational programme, referred to her cultural work as ‘partisaning’. This is a type of work that aims to challenge and transform social realities and traditional ways of knowing about minorities established within national and EU visions. ‘What can Otherness bring to the society?’, Daria asked and explained that this Otherness encompasses the complex identities and intersectional experiences of individuals, so the focus is no longer on integrating specific groups into the society, but on integrating society based on diversity. Daria recognised from the start, however, that challenging settled views would not be easy, as this topic, in her words, ‘is a territory of conflict’. In this section, I will discuss the attempts by MeM members like Daria to reframe the concept of minority beyond the view of a threatening Other through engagement. Although successful in theory, these efforts face complex political, socio-economic, ideological and cultural challenges in practice.

According to Lene Hansen (2012: 543), rearticulation, meaning a fundamental transformation in thinking about the identities and interests of Selves and Others beyond the friend-enemy distinction, is one of the four forms that offers a solution against securitisations (the other being changes induced through stabilisation, replacement and silencing). Although rearticulation is desired, Hansen acknowledges that it is never a straightforward process, but rather a product of power dynamics and conflicting perspectives. Concepts, ideas and big social issues are often fraught with numerous controversies, which partially explains the entangled complexities of (de)securitisation.

The approach of the EU towards the protection of minority rights is a good case in point, which remains highly fragmented and lacks coherence, despite some positive developments (Ahmed 2015). Additionally, it is objectivating and often suffers from groupism. For example, the European Commission’s ‘Migration and Home Affair’ website defines minority as a ‘non-dominant group which is usually numerically less than the majority population of a State or region regarding their ethnic, religious or linguistic characteristics and who (if only implicitly) maintain solidarity with their own culture, traditions, religion or language’ (Sironi, Bauloz & Emmanuel 2019). Within another international organisation, the Council of Europe, the minority rights appear as something to be ‘granted’ to individuals who need to be ‘enabled to participate fully and equally in society’ (Advisory Committee 2016: 4, 5). These definitions exemplify how the authors in authority (i.e. state actors) continue to speak on behalf of the cumulative Other, perpetuating power hierarchies between providers and the objects of responsibility and reinforcing the distinction between the Selves and Others.

It is against these understandings anchored in (supra)national discourses that MeM set itself to work against. Two major premises were then laid out by the project members. The first was a definition of minority that went beyond groupism, which is at the heart of the ‘stranger making’ process. In contrast, MeM proposed to approach minorities through the lens of ‘exclusion’, which allowed for a broader definition of them as ‘individuals and groups who are not included in the socio-cultural life of a community, neighbourhood, city, society for different reasons (e.g. intersectionality)’. The second premise was about agency, and the view that minorities should be seen as ‘actors and agents’ capable to challenge these exclusions.

In an effort to legitimise these viewpoints and transform rigid national cultural-political understandings, the MeM project referenced global discourses on diversity as a ‘common heritage of mankind’[3] while also exposing the inherent critiques of such discourses through its three-month educational programme. The international educational programme was developed collaboratively by MeM partners to convey diversity to future art-mediators. With the help of international cultural activists, curators and educators, it sought to explore topics such as decolonisation, intercultural competencies, self-reflexivity, anti-oppression and social justice. The programme also incorporated several widely recognised mediation methods, including nonviolent communication, visual thinking strategies, participatory walks and story circles, to encourage participants’ peer-to-peer exchange and create shared knowledge spaces.

Although not its primary goal, the positive and trusting relationships that formed between individuals from different countries and social backgrounds as a result of their interactions actively counterposed what Browning (2017: 43) calls a ‘zero-sum understanding of the interdependent nature of security’, where the security of one relies inherently on the insecurity of another. Situated firmly within global frameworks on justice and diversity, the process of unlearning previous ways of knowing about each other within the MeM project fostered a cooperative approach to life. Some MeM participants commented on their experiences in the project as transformative, fostering a sense of belonging, and being heard: ‘We have created a micro-society, a community, and it worked wonders. I felt constant support at these uneasy times.’ Or ‘After-effect of the project – a feeling of happiness, belonging, even euphoria’.

At the same time, while the project helped to create a ‘micro-community’ with a strong sense of agency, its broader consequences in terms of rearticulation through engagement and exchange are worth considering. This becomes particularly complex when viewed in the context of specific local historico-political and symbolic contexts, and different perspectives and sensitivities. To address these issues, I will examine the recent transformations of the Russian Museum in Tallinn.

Estonian Russian Museum: Rearticulating Russian speakers

Despite facing numerous challenges, the process of reconceptualising static ideas of communities did occur locally, as evidenced by the Tallinn Russian Museum. Being severely underfunded and dependent on local political structures, the museum has transformed, at least in some ways, into a space for exploring and expressing different conflicting interpretations of belonging, Russianness and home in recent years.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Estonia has been engaged in a project of national revival, reconfiguring its national identity, viability, safety and security (Jašina-Schäfer 2022: 42). By imposing certain cultural and political narratives, and implementing a restrictive design of political membership through citizenship policies and language laws, Estonia’s political elites neatly drew the contours of legitimate national membership (ibid.).[4] This came along the announcement of Estonia’s ‘return to the western world’ (Lauristin et al. 1997) and the subjectification of Russian speakers as ‘logical opposites’ to Estonians (Feldman 2005: 224). According to Merje Kuus (2004: 199), today it is commonplace in both Estonia and the western media ‘to presuppose deep-seated civilisational difference between Estonia and Russia’ and by extension between Estonians and Russian speakers who constitute about 25 percent of the population and are marked by high levels of ethnic and cultural heterogeneity.[5] This civilisational divide is reflected in the earlier academic representations of Russian speakers as ‘industrial people, [who] more than others, had been integrated into the Soviet ideological system’ and, therefore, need special adaptation and integration ‘before they can become equal members of the legal-political system and the common civic culture and ideology’ (Kirch & Kirch 1995: 439, 441).

Being perceived as civilisationally and culturally distinct, it is not surprising that Russian speakers emerged as a potential threat to Estonia’s stability and its national identity. Since independence, this has resulted in Russian speakers being excluded from the decision-making process, leaving them with virtually no room to express their own perspectives on the past, present and future. Despite some changes in official approaches to belonging and national identity over the last thirty years, recurrent instances of politicians and non-state actors slipping into ethno-nationalist narratives of difference continue to marginalise many Russian speakers (Jašina-Schäfer 2022: 42).

In this context, the Russian Museum can be seen as a reminder of the uncomfortable Otherness that Estonian politicians would rather ignore. However, it is worth noting that until recently, the museum itself perpetuated a very static and artificially purified story of local Russian speakers. Between 2010 and 2020, the exhibitions focused solely on specific themes such as the history of the Russian language and education, and local historical figures such as Peter the Great. According to current employees, a lack of clarity about the museum’s mission and place in society led to growing detachment from the actual concerns of people whose histories it sought to purify and neatly portray. In fact, several people I spoke to outside the museum were not even aware of its existence and associated it with numerous stereotypes.

Change in leadership and engagement with MeM, which the new head clearly prioritised, marked a new chapter in the museum’s history. It presented an opportunity to address its growing irrelevance, which was caused by a failure to review its colonising museological practices and to effectively engage with its audiences. As a first step, the museum conducted interviews with Russian speakers, the results of which challenged the idea of a cohesive ‘Russian-speaking community’ that the museum as well as other political and academic figures had been reconstructing for years. Beyond a shared language, the only commonality among Russian speakers was a sense of alienation rooted in non-acceptance by society at large. This alienation was not experienced universally, but varied across generations, genders, place of residence and class. In light of this fragmentation, the central question became how to depict local Russian speakers without perpetuating narrow images.

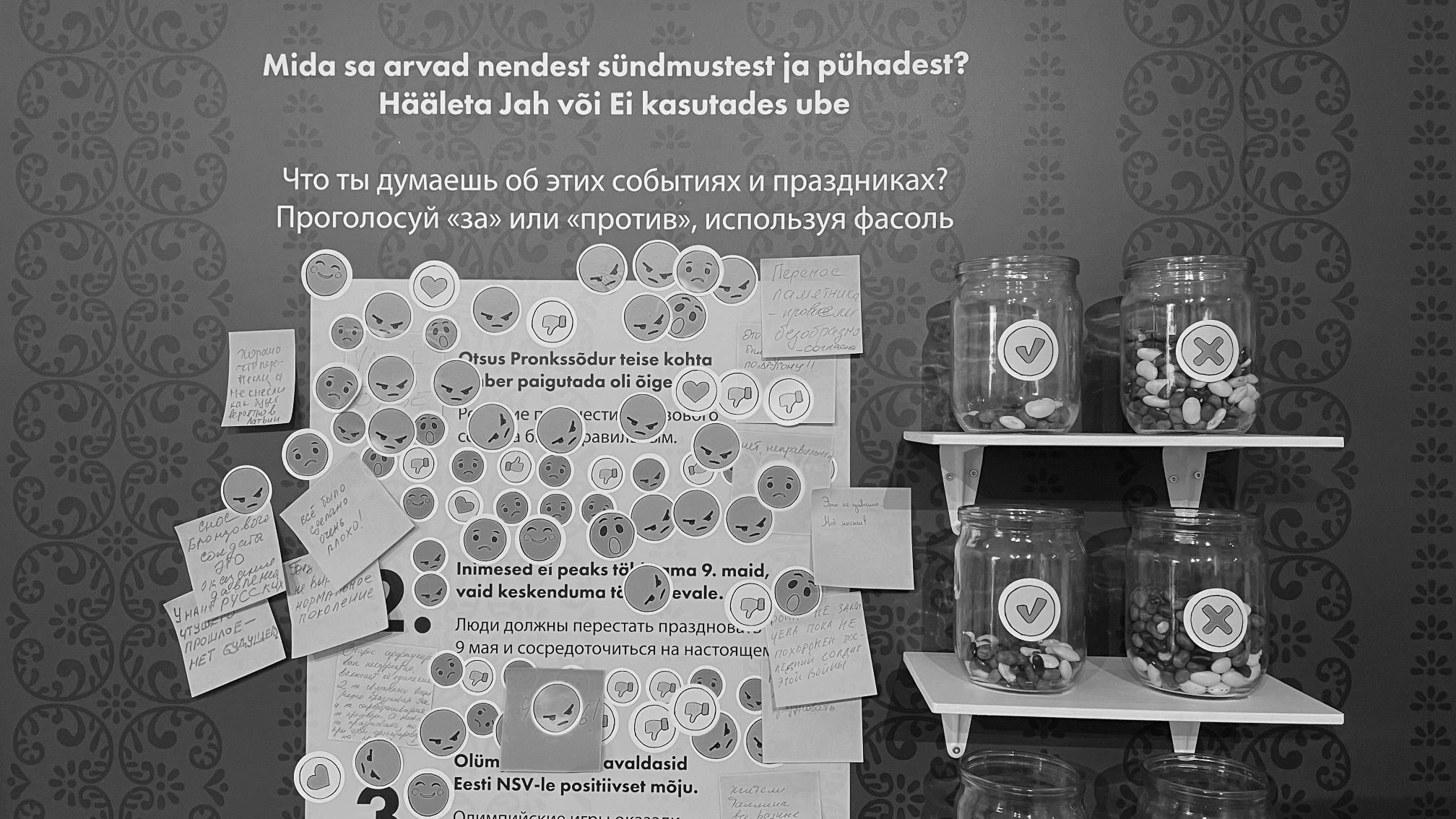

Trying to break away from the linear reproduction of culture, the employees recall being inspired by MeM’s educational programme and becoming eager to join a widespread move towards a collaborative museology based on equal participation. The project, in turn, provided crucial support, ideologically, thematically and financially, allowing the creation of the interactive exhibition ‘Museum’s laboratory: the story of Estonian Russians’. The exhibition placed a special focus on individual stories and was divided into four parts: identity and its diversity beyond national origin; the intertwined history of Estonian society; the everyday experiences where personal stories, emotions and life intersect; and the Russian language as a bridge connecting spaces, times and scales. Through provocative statements from politicians and everyday stories from people, the laboratory invited visitors to ‘watch, talk, discuss, share! Don’t criticize, but respond with your personal story. This is an opportunity to leave your mark on the exhibition space of the museum’ (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Laboratory

Source: Meeli Küttim, courtesy of the museum and reproduced with its permission

The engagement was clearly palpable, as evidenced by the sticky notes that covered the walls, with visitors commenting, arguing with each other and starting new conversations. Lena, who has been a driving force behind the museum’s redefinition, stated that ‘the museum became a safe space, where people can share their feelings openly. People have a lot to say, but do not have space where to speak’. The dialogue between different segments of Estonian society has been long overdue and there is a pressing need for a platform for those whose opinions are at odds with the mainstream. This includes those who still celebrate the 9th May as Victory Day, those who mourn the removal of the T-34 tank monument in Narva and those people who speak the Russian language and consider themselves Estonian.[6]

In contrast, the laboratory became a space for contestation, where different hegemonic political projects could be usefully confronted (Mouffe 2005: 5); a space where the civilisational Otherness of Russianness was challenged and reconstructed as a polyphony of historically grounded social experiences, relationships and senses of belonging. When engaged properly, these alternative visions of community can go beyond the reductive and divisive images of identities promoted by nation-builders. However, as Lena admitted with disappointment, the government still does not understand the importance of the laboratory, and its impact is lost in the dominant Estonianised narratives about the nation, which dominate regardless of elite circulation and exclude alternative views as unimportant or even threatening.[7] Attempting to support people’s rights as active agents, the museum has undergone drastic changes, but has yet to reach beyond and influence the Estonian nation state-building process, which is primarily designed for and in the name of ethnic Estonians (Feldman 2005).

Overall, this discussion highlights two key points. On the one hand, it shows how the museum, by actively engaging people whose opinions remain marginalised from the Estonian mainstream, became an architect(ure) of new sociability filled with new and complex meanings about the lives of Russian speakers. In this process, MeM and its ‘micro-community’ played a crucial role of ideological, financial and moral support for these transformations to occur. At the same time, the museum is severely understaffed and lacks the interest of the general public and political elites to compete with broader national discourses around Estonianness and other actors shaping those discourses. A collaborative museology requires substantial resources of time and personnel, which the museum currently lacks. As a result, employees often mention feelings of exhaustion and burnout, which has limited their ability to take a more proactive stance. This is especially apparent in light of the ongoing war in Ukraine, where the museum is often left out of the discussions surrounding the position of Russian speakers.

Power-sharing and inclusion of minority voices

The example of the Russian Museum mentioned above illustrates well the difficulties in rearticulating and institutionalising a non-threatening identity of constructed Otherness, which involves challenging previous power dynamics and discussing power-sharing. Power-sharing, seen by its proponents as a forward-looking method for managing deep societal divisions and promoting democratic accommodation of difference, has recently been criticised for its unclear conceptualisation, leading to questions about its implementation and governance (McCulloch 2017: 7; Binningsbø 2013). Feminist and post-colonial scholars have also criticised power-sharing practices as a guise for progressive politics that reinforces Othering in the name of inclusion (Ahmed 2012: 51; Guenther 2011; hooks 2015). As a result, power inequalities and asymmetrical relationships persist across political, social, symbolic and material realms, while discourses about the Other continue to silence those whose Otherness they intend to celebrate and protect. As bell hooks (2015: 233) states, there is ‘no need to hear your voice when I can talk about you better than you can speak about yourself’.

The discussion of power dynamics, which plays a crucial role in the securitisation process (Langenohl & Kreide 2019), became a central focus for the MeM project and its efforts to reconfigure the approaches to minorities. Criticising the way power is often viewed as a ‘possession’, the participants aimed to operationalise a relational approach to power through a focus on different forms of ‘inclusion’. Inclusion was collaboratively defined as transparent dialogue and relational engagement among different levels of society and was pursued through mechanisms of participatory art work. Based on survey responses at the end of the project, the external evaluator later deemed these mechanisms a ‘success’, showing how the programme significantly changed participants’ attitudes towards inclusion to ‘a great’ or ‘very great extent’.

While the power-sharing approach through inclusion brought about some transformative changes, it was not an easy process. For instance, the understandings reached within the MeM Finnish local team that focused on the experiences of Russian speakers did not transfer smoothly into the institutional practices of Cultura Foundation, leading to clashes with the discourses promoted by some of its other members. This highlights the ambiguity of the (de)securitisation process, where multiple securitising practices and countermoves coexist and occur relationally ‘between different actors, across different discourses and between different scales of power figurations’ (Langenohl & Kreide 2019: 20). Let us take a closer look at this.

Finland’s Cultura: Moving towards inclusion?

In contrast to Estonia, the Russian-speaking population in Finland is significantly smaller, and the securitising moves have not resulted in exceptional measures within the political-legal framework. Altogether they comprise around 1.6 percent of the populations, a share that has steadily increased since 1991, from fewer than 10,000 to around 88,000 (Statistics Finland 2021). Their history of arrival in Finland, which is relatively ethnically homogenous, is also different. While Estonian Russian speakers were displaced as a result of geopolitical reconfigurations that moved the borders over them, the majority of Finland’s Russian speakers migrated after the collapse of the Soviet Union, choosing to move to Finland for a better life or other reasons. These differences in origins and outlooks also explain their different status. Borrowing a term from Darja Klingenberg (2019), their position could be described as ‘conspicuously inconspicuous’ migrants: Finland’s Russian speakers are rarely visible in public debates and are predominantly viewed as well-adjusted people who ‘cherish ties to both Finnish society and Russian culture, and have a positive outlook on their future in Finland’ (Renvik et al. 2020: 465).

This being said, discourses that depict their lack of integration (Tiido 2019) can quickly resurface, particularly when the media portrays Russian speakers as a collective susceptible to Russia’s propaganda. This has become increasingly feasible in recent years, following the annexation of Crimea and the ongoing war in Ukraine, where Russian migrants’ involvement in the crimes of Russia’s government is widely discussed. In general, several scholars note how due to historical conflicts between Finland and Russia, Russian speakers often face mistrust and experience discrimination in the labour market and other spheres of life, which can lead to growing detachment from Finnish society (Renvik et al. 2018). To address these negative experiences, the Ministry of Education and Culture established the Cultura Foundation in 2013, with the goal of promoting two-way integration. This entails collecting and providing information to institutions to improve their interactions with minorities and creating a better understanding for Russian speakers of how Finnish society works.

The MeM project, which was primarily conceptualised by several employees of the Cultura Foundation, did not necessarily share the institution’s visions of integration and attempted to challenge it in some ways. During my conversation with Daria, who moved to Finland from Russia about a decade ago, she explained that MeM prioritises ‘inclusion’ because ‘integration’ has a frequently misused discriminatory connotation. ‘It means that some people are already good enough to be a part of the society, and some are not’, Daria said. The discourse of integration reinforces the idea that people ‘need to change themselves to be able to join the society in full sense, so to learn the language, learn new social rules or habits, and so on, and they should somehow adjust themselves to this already existing unity which is the society’. Daria considered this particularly problematic as members of the Finnish society are rarely scrutinised through the prism of integration. Inclusion, as she explained to me, is, in turn, not about making everybody an average Finn (which is by default a desired outcome) but about enabling people to join on their own terms and acknowledging their agency to decide whether and how they want to change.

The concept of integration, which was seen by some employees of Cultura as a top-down and objectifying process, continued to be a desirable outcome for others. This led to a ‘clash of meanings’ (as put by one respondent) and emotional tensions within the organisation, causing initially the neglect of the MeM project. There was even a question whether MeM belonged within the framework of the organisation that prioritises integration. Although Cultura’s director later acknowledged how MeM and the method of art mediation for inclusion became a ‘game-changer’ for him personally and the institution as a whole, the tensions between meanings still prevail and were resurfaced with new ferocity after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

On the one hand, Cultura has adopted the central principles of MeM and actively promotes diversity, equality and inclusion (DEI) in all its documents and annual programmes. This is visible in other projects that the organisation initiated, such as ‘Dialogues in times of crisis’, which emphasises the importance of discussing experiences of fear, despair and misunderstanding in small groups in times of war. Recently, employees also drafted a letter to Turku county election candidates proposing DEI measures to make social and health services more accessible.

On the other hand, however, there still remain numerous reservations about actually empowering Russian speakers, promoting their agency or engaging in dialogue with them. The view that minorities must adjust to the new realities in Finland continues to dominate everyday narratives. During a panel discussion at Cultura’s conference on ‘The future of the sense of belonging’ in September 2022, I witnessed, for instance, how a Russian-speaking woman from the audience who came forward to express her feelings of marginalisation in Finland was disregarded by Cultura employee who preferred to cite survey results showing that the majority of Russian speakers claimed not to have experienced discrimination.

This incident, and the overall atmosphere at Cultura, serve as a reminder that the terrain in which initiatives like MeM operate is shaped by previous hegemonic practices and other ways of knowing (Mouffe 2005: 33). As it is a contested field, transformative processes cannot simply be achieved through abstract negation. The disarticulation of existing practices, which MeM members saw as exclusionary, caused discomfort and revealed personal and institutional differences. However, it can also be argued that these differences were crucial in creating new understandings and practices that challenge hegemonic constructions driving securitisation. One Cultura employee noted that, over time, the open confrontation that was evident at the start of the project evolved into discussion and, at least, sparked some interest in each other’s perspectives.

Engaging audiences and their emotions

In addition to countering the objectifying perspectives towards minorities and striving to shift power dynamics, MeM was strongly dedicated to changing the general attitudes towards audience engagement. As described by the project, MeM regarded both its mediators and members of the public as active ‘makers and experts by experience’. The focus of this approach was on individual emotions and bodies, which were seen as important avenues through which people understand and interpret social worlds around them. MeM aimed to explore the emotional and cultural reserves that are inherent to a local social imaginary, and the thoughts and feelings that are evoked by art and interactions with others. This section will briefly examine how MeM sought to tap into individual emotions and what could be considered the political implications of these emotional practices.

With the use of art as a form of creative communication, MeM sought to foster inter- and intra-communal exchange and dialogue, through which the change in perceptions of the Self and the Other could take place. The objective was to incorporate the affective and social intricacies that form the political landscape and make up audiences (see also Morrow 2018; Van Rythoven 2015; Zembylas 2020), but also to challenge the traditional notion of audiences as ‘passive vessels waiting for emotions to be authoritatively spoken into them’ (Van Rythoven 2015: 463).

Above, I already discussed in detail the case of the Tallinn Russian Museum, which itself became a platform for listening to and exhibiting different stories of Russian speakers. Some people attempted to confront feelings of being unwanted elements from the Soviet past, others spoke of discovering their own sense of belonging to Estonia through a sense of nonbelonging to Russia, and still others spoke of their hard work and deservingness to be a part of Estonian community. The Finnish local team, in turn, decided to move their exhibition ‘Connected’ entirely online in order to avoid social backlash while trying to convey the emotional labour of Russian speakers in understanding the notions of home and identity in the midst of the devastating consequences of war for Ukrainians.[8]

In the stories shared through ‘Connected’, the quest for belonging was defined by personal experiences such as divorce, parenthood and limited living space. For example, one participant, Evgenii, wrote in a letter about home where he did not always feel accepted and found security only in his own body and through dance: ‘Regardless of the weather outside or the crises that shake the world and me personally, when I dance, everything becomes distant and illusory. Dance is the guardian of a fortress where I live.’ Another participant, Hermanni, said that he always felt like something was missing: ‘It’s hard to feel like you belong somewhere if you can’t be fully physically present there.’ When later a local mediator, Nadezhda, engaged audiences around this exhibition and around these letters, she noted the diverse range of emotions expressed by the audience, ‘from genuine tears to joyful revelations’. The discussion uncovered many shared painful experiences among Russian speakers in Finland, but it also provided participating individuals an opportunity to better understand themselves, their pasts and presents.

These various artistic venues help to reveal ‘the liveliness, disruption, and tension that affect and emotion create’ (Morrow 2018: 18). Just like the differences in thinking about inclusion discussed earlier, making previously unknown experiences and emotions of marginalised people visible through exhibitions of personal stories, photographs or other material objects has the potential to reorient, interrupt and transform previous power structures. The progression from the unknown to briefly known inspires the motivation to reevaluate and reconsider the practices of subjectivation and securitisation.

But the practices within MeM must also be viewed in a broader context. Two major events – the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine – had significant impacts on the project’s interactions with audiences. The pandemic caused significant disruptions, especially in the early stages, as nearly all cultural and art venues were closed, making public exhibitions and real-life art mediation practices difficult. For some participants, the shift towards online platforms was physically and mentally challenging, with one mediator stating that ‘MeM was very demanding on my well-being and actually it was taking a lot of resources from me’. The war added a new dimension, affecting teams and organisations on all levels. While one participant from Latvia expressed feeling an existential threat from Russia: ‘there is no point in doing any project if the next thing is the war with Russia’, others from Estonia and Finland experienced an existential crisis of identity as Russian speakers, questioning their relationship to Russia and to their Russian-speaking friends and family. In a new world where Russianness has acquired a negative connotation, their role as cultural workers was too called into question. As one mediator from Finland put it, ‘everything connected to Russia raised negative emotions and it was risky to do any public dialogue around it’.

Conclusion

This paper aimed to demonstrate the impact of the cultural project and its constituent institutions on the dynamics of securitisation. Although cultural work is often not the focus of security studies, it plays a significant role in challenging power balances, creating or disrupting understandings of difference. By exploring the relationship between critical security studies and cultural work, this paper has laid the foundation for a more nuanced approach towards exclusions and how they are negotiated in society more generally, which may be beneficial to theories and empirical research on (de)securitisation in several ways.

First, the alternative approaches to minorities, power-sharing and audience engagement developed within MeM can be considered as valid countermoves to dominant representations of minorities as threats, as passive subjects or collectives. Through creating new spaces for minority voices, promoting dialogue and exchange between speakers and audiences, and revealing previously unknown stories and differences in perspectives, MeM has disrupted the status quo of things and highlighted areas in need of change. This critical orientation has not only made people aware of what recedes from the view, but has also strengthened local communities’ ability to differentiate themselves from dominant discourses and become more resilient to crises in which minorities are often securitised.

Second, by using a scalar gaze, we were able to see the socio-political field as one of antagonisms, balancing the relationship between different actors, contexts and geographies (see also Mouffe 2005). This perspective helps explain, at least in part, the ambiguity of any (de)securitisation practices, including the ones discussed in this papers, where creative cultural work coexists uneasily with other national or local institutional discourses, as well as global events. As there is always a risk of ‘reinforcing rather than disrupting securitisation discourses’ (Zembylas 2020: 15), it is important to carefully balance new interventions with potential pushbacks that are the result of previous practices and ways of knowing. While many institutions, including cultural ones, remain unaware of how they contribute to the process of ‘stranger-making’ (Ahmed 2012), engaging them can only benefit future studies of (de)securitisation. Future research should therefore pay more attention to the efforts of cultural organisations to transform, tracing the connection between knowledge production, transformation, and their link to securitisation.

***

Acknowledgements

The initial research findings were presented during the 2021 research seminar ‘Europe’s Crises and Experience of Leadership’ in Tartu. I am grateful to Andrey Makarychev and Thomas Diez for encouraging me to turn these findings into a published article. I am indebted to the MeM-team, in particular to Daria Agapova and Irina Spazheva, for inviting me to join the project on its journey towards diversity and inclusion, and for including me in all discussions and processes from the outset. I also want to thank journal editors and two peer reviewers for their helpful feedback on earlier versions of this article.

Alina Jašina-Schäfer is a post-doctoral researcher at the department of Cultural Anthropology and European Ethnology, University of Mainz. She studied Central and East European Studies at the University of Glasgow, International Relations at the Central European University in Budapest and holds a PhD in Cultural Studies from the Justus Liebig University Giessen. In the past Alina has published on topics such as exclusion, belonging and home, horizontal citizenship, gendered experiences of work, epistemic biases and knowledge production. In her current research project, she is exploring the changing systems of value around human worth in the context of migration.

References

Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (2016): The Framework Convention: A Key Tool to Managing Diversity through Minority Rights. Thematic Commentary No. 4// The Scope of Application of the Framework for the Protection of National Minorities (ACFC/56DOC(2016)001). Council of Europe, 27 May, <accessed online: https://rm.coe.int/16806a4811>.

Ahmed, S. (2000): Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality. London & New York: Routledge.

Ahmed, S. (2012): On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Ahmed, T. (2015): The EU’s Relationship with Minority Rights. In: Psychogiopoulou, E. (ed.): Cultural Governance and the European Union. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Al, S. & Byrd, D. (2018): When Do States (De)securitise Minority Identities? Conflict and Chance in Turkey and Northern Ireland. Journal of International Relations and Development, 21, 608-34.

Apostolov, M. (2018): Religious Minorities, Nation States and Security: Five Cases from the Balkans and the Eastern Mediterranean. New York: Routledge.

Austin, J. & Beaulieu-Brossard, P. (2018): (De)securitisation Dilemmas: Theorising the Simultaneous Enaction of Securitisation and Desecuritisation. Review of International Studies, 44 (2), 301-323.

Bakić-Hayden, M. (1995): Nesting Orientalisms: The Case of Former Yugoslavia. Slavic Review, 54 (4), 917-931.

Balzacq, T. (2011): Enquiries into Method: A New Framework for Securitisation Analysis. In: Balzacq, T. (ed.): Securitisation Theory: How Security Problems Emerge and Dissolve. London & New York: Routledge, 31-55.

Binningsbø, H. (2013): Power Sharing, Peace and Democracy: Any Obvious Relationships? International Area Studies Review, 16(1), 89-112.

Bourbeau, P. (2011): The Securitisation of Migration: A Study of Movement and Order. New York: Routledge.

Browning, C. (2017): Security and Migration: A Conceptual Exploration. In: Bourbeau, P. (ed.): Handbook on Migration and Security. Edward Elgar, 39-59.

Buzan, B., Wæver, O. & de Wilde, J. (1998): Security: A New Framework for Analysis. London: Lynne Rienner.

Çağlar, A. & Glick Shiller, N. (2018): Migrants and City-Making. Dispossession, Displacement & Urban Regeneration. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Canetti-Nisim, D., Ariely, G. & Halperin, E. (2008): Life, Pocketbook, or Culture: The Role of Perceived Security Threats in Promoting Exclusionist Political Attitudes toward Minorities in Israel. Political Research Quarterly, 61 (1), 90-103.

Carlà, A. & Djolai, M. (2022): Securitisation of Minorities under Covid-19. European Yearbook of Minority Issues, 19 (1), 107-131.

Carr, D. (2003): The Promise of Cultural Institutions. Lanham: Altamira Press.

Cohen, N. S. (2015): Cultural Work as a Site of Struggle: Freelancers and Exploitation. Marx and the Political Economy of the Media, 79, 36-64.

Cole, M. (2022): We Need to Talk about Narva. ERR News, 22 August, <accessed online: https://news.err.ee/1608691990/feature-we-need-to-talk-about-narva>.

Comunian, R. & England, L. (2020): Creative and Cultural Work Without Filters: Covid-19 and Exposed Precarity in the Creative Economy. Cultural Trends, 29 (2), 112-128.

Demossier, M. (2014): Sarkozy and Roma: Performing Securitisation. In: Maguire, M., Frois, C. & Zurawski, N. (eds.): The Anthropology of Security: Perspectives from the Frontline of Policing, Counter-Terrorism and Border Control. London: PlutoPress, 24-45.

Dimari, G. (2021): Desecuritising Migration in Greece: Contesting Securitisation Through ‘Flexicuritisation’. International Migration, 00, 1-15.

Djolai, M. (2021): Introduction: Fighting for Security from a Minor Perspective and Against Securitisation of Minorities in Europe. Journal of Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe, 20(1), 1-23.

Donnelly, F. (2015): The Queen’s Speech: Desecuritising the Past, Present and Future of Anglo-Irish Relations. European Journal of International Relations, 21(4), 911-934.

Donnelly, F. (2017): In the Name of (De)securitisation: Speaking Security to Protect Migrants. Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons? International Review of the Red Cross, 99(1), 241-261.

Duffield, M. (2005): Getting Savages to Fight Barbarians: Development, Security and the Colonial Present. Conflict, Security & Development, 5(2), 141-159.

Färber, C. (2018): The Absence of Methodology in Securitisation Theory. E-international Relations, 7 August, <accessed online: https://www.e-ir.info/2018/08/07/the-absence-of-methodology-in-securitisation-theory/>.

Feldman, G. (2005): Essential Crises: A Performative Approach to Migrants, Minorities, and the European Nation-State. Anthropological Quarterly, 78(1), 213-246.

Fraser, N. (2010): Scales of Justice: Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World. New York: Columbia University Press.

Fridolfsson, C. & Elander, I. (2021): Between Securitisation and Counter-Securitisation: Church of Sweden Opposing the Turn of Swedish Government Migration Policy. Politics, Religion & Ideology, 22(1), 40-63.

Glick Schiller, N. & Çağlar, A. (2016): Displacement, Emplacement and Migrant Newcomers: Rethinking Urban Sociabilities within Multiscalar Power. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power, 23 (1), 17-34.

Glick Schiller, N. & Faist, T. (2009): Migration, Development, and Social Transformation. Social Analysis, 53 (3), 1-13.

Glück, Z. & Low, S. (2017): A Sociospatial Framework for the Anthropology of Security. Anthropological Theory, 17 (3), 281-296.

Goldstein, D. (2010): Toward a Critical Anthropology of Security. Current Anthropology, 51(4), 487-517.

Green, S. (2005): Notes from the Balkans: Locating Marginality and Ambiguity on the Greek-Albanian Border. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Guenther, L. (2011): The Ethics and Politics of Otherness: Negotiating Alterity and Racial Difference. philoSOPHIA, 1(2), 195-214.

Hansen, L. (2012): Reconstructing Desecuritisation: The Normative-Political in the Copenhagen School and Direction for How to Apply It. Review of International Relations, 38(03), 525-546.

hooks, b. (2015): Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics. New York & London: Routledge.

Huysmans, J. (2006): The Politics of Insecurity: Fear, Migration and Asylum in the EU. London & New York: Routledge.

Huysmans, J. (2014): Security Unbound: Enacting Democratic Limits. London & New York: Routledge.

Huysmans, J. (2019): Foreword: On Multiplicity, Interstices and the Politics of Insecurity. In: van Baar, H., Ivasiuc, A. & Kreide, R. (eds.): The Securitisation of the Roma in Europe. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, v-x.

Innes, A. (2015): Migration, Citizenship and the Challenge for Security: An Ethnographic Approach. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jašina-Schäfer, A. (2022): Unveiling the Researcher’s Self: Reflexive Notes on Ethnographic Engagements and Interdisciplinary Research Practices. In: McGlynn, J. & Jones, O. T. (eds.): Researching Memory and Identity in Russia and Eastern Europe: Interdisciplinary Methodologies. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 41-56.

Jašina-Schäfer, A. (2021): Everyday Belonging in the Post-Soviet Borderlands: Russian Speakers in Estonia and Kazakhstan. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Jaskulowski, K. (2017): Beyond National Security: The Nation-State, Refugees and Human Security. Kontakt, 19 (4), 311-316.

Jutila, M. (2006): Desecuritising Minority Rights: Against Determinism. Security Dialogue, 37(2), 167-185.

Kassim, S. (2017): The Museum Will Not Be Decolonised. Media Diversified, 15 November, <accessed online: https://mediadiversified.org/2017/11/15/the-museum-will-not-be-decolonised/>.

Kirch, M. & Kirch, A. (1995): Search for Security in Estonia: New Identity Architecture. Security Dialogue, 26 (4), 439-448.

Klingenberg, D. (2019): Auffällig unauffällig. Russischsprachige Migrantinnen in Deutschland [Conspicuously Inconspicuous. Russian-Speaking Migrant Women in Germany]. Osteuropa, 69(9-11): 255-276.

Kóczé, A. (2019): Illusionary Inclusion of Roma Through Intercultural Mediation. In: van Baar, H., Ivasiuc, A. & Kreide, R. (eds.): The Securitisation of the Roma in Europe. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 183-207.

Krätke, S. (2011): The New Urban Growth Ideology of ‘Creative Cities’. In: Brenner, N., Marcuse, P. & Mayer, M. (eds.): Cities for People, not for Profit: Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City. London & New York: Routledge, 135-50.

Kudaibergenova, D. (2017): The Archaeology of Nationalizing Regimes in the Post-Soviet Space. Problems of Post-Communism, 64:6, 342-355.

Kuus, M. (2004): ‘Those Goody-Good Estonians’: Towards Rethinking Security in the European Union Candidate States. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 22, 191-207.

Langenohl, A. & Kreide, R. (2019): Introduction: Situating Power in Dynamics of Securitisation. In: Kreide, R. & Langenohl, A. (eds.): Conceptualising Power in Dynamics of Securitisation: Beyond State and International System. Baden-Baden: Nomos, 7-25.

Langenohl, A. (2019): Dynamics of Power in Securitisation: Towards a Relational Understandings. In: Kreide, R. & Langenohl, A. (eds.): Conceptualising Power in Dynamics of Securitisation: Beyond State and International System. Baden-Baden: Nomos, 25-67.

Lauristin, M., Vihalemm P., Rosengren, K. & Weibull, L. (eds.) (1997): Return to the Western World: Cultural and Political Perspectives on the Estonian Post-communist Transition. Tartu: Tartu University Press.

Lynch, B. (2016): ‘Good for You, but I Don’t Care’: Critical Museum Pedagogy in Educational and Curatorial Practice. In: Mörsch, C., Sachs, A. & Sieber. T. (eds.): Contemporary Curating and Museum Education. Bielefeld: transcript, 255-269.

Maguire, M., Frois, C. & Zurawski, N. (eds.): The Anthropology of Security: Perspectives from the Frontline of Policing, Counter-Terrorism and Border Control. London: PlutoPress.

Malkki, L. (1992): National Geographic: The Rooting of Peoples and the Territorialisation of Identity among Scholars and Refugees. Cultural Anthropology, 7(1), 24-44.

Malloy, T. (2013): Introduction. In: Malloy, T. (ed.): Minority Issues in Europe: Rights, Concepts, Policy. Berlin: Frank & Timme, 13-23.

McCall, V. & Gray, C. (2013): Museums and the ‘New Museology’: Theory, Practice and Organisational Change. Museum Management and Curatorship, 29 (1), 19-35.

McCulloch, A. (2017): Introduction: Contemporary Challenges to Power-Sharing Theory and Practice. In: McCulloch, A. & McGarry, J. (eds.): Power-Sharing: Empirical and Normative Challenges. London & New York: Routledge, 1-16.

Mignolo, W. (2014): The North and the South and the West and the East. A Provocation to the Question. Ibraaz, 8 November, <accessed online: https://www.ibraaz.org/essays/108>.

Morrow, A. (2018): Layers of Affect: The Liminal Sites of Method. Critical Studies on Security, 7(1), 18-33.

Mouffe, C. (2005): On the Political. Oxford: Routledge.

Pedersen, M. & Holbraad, M. (2013): Introduction: Times of Security. In: Holbraad, M. & Pedersen, M. (eds.): Times of Security: Ethnographies of Fear, Protest, and the Future. New York & London: Routledge, 1-28.

Renvik, T., Brylka, A., Konttinen, H., Vetik, R. & Jasinskaja-Lahti, I. (2018): Perceived Status and National Belonging: The Case of Russian Speakers in Finland and Estonia. International Review of Social Psychology, 31(1), 1-10.

Renvik, T., Jasinskaja-Lahti, I. & Varjonen, S. (2020): The Integration of Russian-Speaking Immigrants to Finland: A Social Psychological Perspective. In: Denisenko, M., Strozza, S. & Light, M. (eds.): Migration from the Newly Independent States. Springer, 465-482.

Roe, P. (2004): Securitisation and Minority Rights: Conditions of Desecuritisation. Security & Dialogue, 35(3), 279-294.

Sandell, R. (1998): Museums as Agents of Social Inclusion. Museum Management and Curatorship, 17(4), 401-418.

Sironi, A., Bauloz, C. & Emmanuel, M. (2019): Glossary on Migration. The IOM UN Migration, 18 June, <accessed online: https://www.iom.int/glossary-migration-2019>.

Skleparis, D. (2017): ‘A Europe without Walls, without Fences, without Borders’: A Desecuritisation of Migration Doomed to Fail. Political Studies, 66(4),1-17.

Smith, B. W. & Holmes, M. D. (2014): Police Use of Excessive Force in Minority Communities: A Test of the Minority Threat, Place, and Community Accountability Hypotheses. Social Problems, 61(1), 83–104.

Statistics Finland (2021): Population and Society. Statistics Finland, last updated 9 March 2023, <accessed online: https://www.tilastokeskus.fi/tup/suoluk/suoluk_vaesto_en.html>.

Tiido, A. (2019): Russians in Europe: Nobody's Tool. The Examples of Finland, Germany and Estonia. ICDS, 1-15, September, <accessed on-line: https://icds.ee/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/ICDS_EFPI_Analysis_Russians_in_Europe_Anna_Tiido_September_2019.pdf>.

van Baar, H., Ivasiuc, A. & Kreide, R. (2019): The European Roma and Their Securitisation: Contexts, Junctures, Challenges. In: van Baar, H., Ivasiuc, A. & Kreide, R. (eds.): The Securitisation of the Roma in Europe. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 1-27.

Van Rythoven, E. (2015): Learning to Feel, Learning to Fear? Emotions, Imaginaries, and Limits in the Politics of Securitisation. Security Dialogue, 46(5), 458-475.

Wæver, O. (1995): Securitisation and Desecuritisation. In: Lipschutz, R. (ed.): On Security. New York: Columbia University Press, 46-86.

Zembylas, M. (2020): Affect/Emotion and Securitising Education: Re-orienting the Methodology and Theoretical Framework for the Study of Securitisation in Education. British Journal of Education Studies, 68(4), 487-506.

[1] For more information on the project, see https://memagents.eu/.

[2] For the analysis of the qualitative data the software NVivo was used. The results stem from a narrative thematic analysis of participants’ interview accounts, surveys with open-ended questions as well as data from MeM communication channels (Facebook, MeM Web-Site and HowSpace). Furthermore, interactional analysis was used to approach selected meetings, focus group as well as ethnographic observations of localities in focus.

[3] See the UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity formulated in 2001.

[4] The 1992 citizenship law refused citizenship rights to the majority of Soviet-era immigrants and their offspring unless they could provide evidence of their familial ties to the pre-war Estonian Republic. Those who could not prove their historical connection were left with three choices: apply for citizenship in another country, accept their legal status as resident ‘aliens’, or undergo the naturalisation process. For more on everyday life of Russian speakers in Estonia see, for example, Jašina-Schäfer (2021).

[5] The term ‘Russian speakers’ refers to different ethnicities – Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Tatars, Poles and others – who during the tsarist Russia and the Soviet Union became heavily Russified and who had migrated to the non-Russian regions.

[6] The war in Ukraine has brought along heated public discussions about the place of Soviet monuments in Estonian public space. Since for the majority population these monuments serve as symbols of Soviet occupation which remained dormant until recent events, the resolution was signed for their removal. For more on the removal of Tank T-34 see Michael Cole (2022).

[7] For a similar discussion on Latvia, see Kudaibergenova (2017).

[8] The exhibition ‘Connected’ was a product of collaboration between the Finnish artist Sanni Saarinen and MeM art mediators. It represented a collection of different stories of home, perception of identity and one’s place at the intersection of different cultures. For more visit: https://www.kytkoksissa.com/kytkoksissa.