Abstract

This comparative case study investigates the financing typologies of Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) and Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) in Turkey. The PKK is a Marxist-Leninist organisation that pursues ethnic separationist policies in Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria. ISIL is a radical Wahhabi network that aspires to re-establish the Caliphate and restore the ‘glory’ of Sharia by defeating the ‘near’ and ‘far’ enemies. Based on primary/secondary interviews, content analysis of unclassified documents and media coverage on counter PKK/ISIL investigations, this study indicates that both organisations have been highly skilful in exploiting the regional licit and illicit enterprises. Financing methods of the PKK and ISIL were similar in complex regional underground economic infrastructure. However, the PKK has been able to develop much more sophisticated financial infrastructure than ISIL due to a longer life span and existence of specialised cadres in the Middle East and Europe. ISIL has failed to develop advanced financing infrastructure mainly due to a shorter life span, loss of territorial control and the UN-US sponsored international sanctions. Both the Marxists and radical Islamists encouraged illicit trade schemes not only to generate funds but also to avoid taxation by the ‘hostile’ regimes.

Keywords

Introduction[1]

The world has been experiencing different waves of terror attacks from entities that have different ideological motivations. Over five decades of research experience on Marxist, ethnic-separatist and religious extremist groups validated that lengthy terror campaigns are expensive ventures. Terror establishments need substantial amounts of funds and resources to maintain their operations. In other words, continuity of terror campaigns depends on a sustainable influx of financial resources. Available research indicates that failure to cover training, equipment, salary, propaganda and other related expenses will eventually lead to the demise of the terror campaigns (Bauer & Levitt 2020; Biersteker et al. 2008; King et al. 2018; Normark & Ranstorp 2015; Schneider & Caruso 2011).

Turkey has a long history of fighting against domestic and international terrorist organisations coming from different ideological backgrounds. This makes the country an outstanding laboratory to investigate terrorism financing typologies. The republic has experienced three waves of terrorism since the 1970s in line with the global geopolitical context. The first wave came out of the ideological battles between the Western and Eastern Blocs in the Cold War context. Leftist revolutionary groups such as the Devrimci Sol (Dev Sol), the Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front (DHKP/C), the Revolutionary Workers and Peasants Party of Turkey (TIKKO), and Turkish Communist Party/Marxist-Leninist (TKP-ML) resisted against Turkey’s pro-western foreign policy and NATO membership (Demirel 2007). The second wave of terrorism came from ethnic separatist Kurdish groups, mainly the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK), whose motivation stems from Marxist-Leninist revolutionary ideology (Alptekin 2020; Sen 2021). The third wave of terrorism came from radical Islamic groups such as Al-Qaeda, Hezbollah and ISIL. Al-Qaeda and Turkish Hezbollah carried out sensationalist terror attacks throughout the 1990s and 2000s, but both organisations gradually disappeared from the scenes (Demirel 2005; Erdem 2016).

The terrorism financing landscape in Turkey has changed intensely since the US invasion of Iraq. A dramatic increase in ungoverned places in Iraq and Syria facilitated an exponential growth of illicit markets linked to Turkey. The subsequent influx of the ISIL operatives under the guise of Syrian refugees complicated the counter terrorism financing initiatives since they developed symbiotic relationships with the radical Salafi jihadists in Turkey (Bozkurt 2021; Eroglu 2018). Unlike its predecessor Al-Qaeda, ISIL cells in the Istanbul, Ankara, Gaziantep, Konya and Adıyaman provinces developed localised self-financing capabilities (Eroglu 2018). With extremely low budgets, ISIL operatives conducted sensational attacks against security forces, recreation centres and party rallies of the People’s Democratic Party (HDP) in various provinces of Turkey (Bozkurt 2021; Erdem 2016; Saymaz 2021).

Financing typologies of the terrorist networks can be significantly different from each other depending on the size, geography, operational target, grand strategy, ideology and level of financial institutionalisation, and the type of administration. Within the broader research question of why terrorist organisations have different financing typologies, we sought to explore how the Marxist PKK and Wahhabi/Salafist ISIL networks generated funds on the same territories. More specifically, we investigated how both organisations have been financed via: i) criminal enterprises, ii) taxation and extortion, iii) legal enterprises, iv) non-profit organisations, v) abuse of social welfare programmes, vi) misuse of informal money transfers and vii) cash couriers.

This qualitative and comparative case study has been composed of two stages. At the first stage, we have reviewed relevant academic publications, international reports, institutional publications, unclassified investigation/prosecution documents, released court decisions, threat assessments and media coverage on terrorism financing incidents in Turkey. Throughout the desk review process, we liaised with potential experts who have significant experience in combatting the financing of terrorism. At the second stage, we conducted 38 semi-structured interviews in the Ankara, Gaziantep, Istanbul and Kahramanmaras provinces. The communications with the pre-identified experts were made both face to face and online (via Skype, Zoom or Microsoft Teams). The interviewees have been selected from a diverse set of backgrounds: current or former law enforcement officers, prosecutors, judges, lawyers, government officials, academics, analysts from Financial Intelligence Units (FIU), and experts from the international organisations.

Literature review

There is a growing body of literature on the financing and resourcing of terrorist entities. Financial strategies of the terrorist networks can be significantly different from each other depending on the size, geography, operational targets, grand strategies and type of administration (Myres 2012; Biersteker et al. 2008; Vittori 2011; King et al. 2018; Wittig 2009). According to Timothy Wittig ‘financing strategies emerge organically from a sort of market violence where “investment” into the terrorist group is shaped by opportunities within a specific social, economic and political milieu’ (Wittig 2009: 146). Wittig maintains that political and economic dynamics are core independent variables in analysis of terrorism financing typologies.

According to Michael Freeman (2011: 463), terrorist networks take into account ‘six criteria’ while generating funding. First, they desire the largest ‘quantity’ of funds to conduct recurrent and fierce attacks. Second, terrorist networks look for self-perceived ‘legitimacy’ of the financing methods in accordance with their ideologies (Freeman 2011: 463). Some networks can involve in drug trafficking, while others may see this trade as illegitimate due to ideological disapproval. Third, ‘security’ of the financing methods is evaluated. Organisation leaders assess whether a particular funding method will bring about new vulnerabilities and draw the attention of the law enforcement agencies or financial intelligence units. Fourth, the networks look for ‘reliability’ and ‘predictability’ of the sources which they can count on consistently. Fifth, organisations want to exercise full ‘control’ over the financial resources and try to prevent external intervention. Sixth, financing methods should be ‘simple’ and should not require ‘specialised skills’ or complicated processes (Freeman 2011: 464).

Financing typologies of the terrorist organisations can also be shaped by the level of institutionalisation in their financial apparatus. In general, the networks with advanced financial establishments tend to procure finances from a diverse set of resources, while premature groups depend on simplistic financing strategies such as bank robbing, kidnapping for ransom or taxing the sympathisers (Clarke 2015; Freeman 2011). Advanced terror networks develop specialised economic intelligence units to explore and exploit sustainable funding opportunities from a diverse set of legal and criminal enterprises (Rudner 2006). The financial apparatus develops short- and long-term budget plans for administrative, operational, training and propaganda expenses (Clarke 2015; Ekici 2021). There is a general consensus among terrorism researchers that failure to establish an effective economic apparatus has been a significant predictor of the demise of the terrorist organisations (Freeman 2011; Myres 2012; Vittori 2011).

The type of the organisation may have an impact on the typology of financing and modus operandi of the networks. Graham Myres (2012) divides the terror networks into two categories: i) elitist and ii) populist. According to Myres, elitist organisations (such as Al-Qaeda) are usually ‘extant social networks or kinship connections available to group entrepreneurs’, on the other hand, populist organisations are ‘more likely to be armed groups that emerge organically from a particular identity culture and whose members are from that community’ (2012: 702). Myres claimed that the populist networks tended to employ methods that are perceived as ‘legitimate’ among the host communities, while the elitist groups followed methods that are approved by their geopolitical masters. In this context, Vittori (2011) found that dependency of the elitist groups on foreign state sponsors undermines the autonomy of their leaderships, especially when they have to report to multiple donors. On the other hand, populist groups (such as PKK, Hezbollah, LTTE) seek to develop in-house and autonomous economic initiatives that endorse the positions of the leadership cadres (Ekici 2021; Geltzer 2011).

The review of the literature clearly indicated that terrorism financing typologies should be investigated in tandem with the ‘resourcing’ concept. According to Vittori (2011), resources include money, liquid assets, ‘tangible goods’, such as weapons, ammunitions and medical supplies, and ‘intangible goods’, such as providing operational safe heavens, protection, training, assisting with propaganda, delivering actionable intelligence and sharing of experience. Many studies indicate that state sponsors and wealthy donors of terrorist networks have been the core actors in terrorism resourcing (Byman & Kreps 2010; Clarke 2015; DeVore 2012). On many occasions, resourcing becomes a lifesaver for the terror networks that engage in prolonged conflicts with the host governments (Vittori 2011). A group of security analysts argue that resourcing strategies of terrorist groups that have asymmetric ties to state sponsors are hardly defined by the leadership cadres (Myres 2012; Biersteker et al. 2008; King et al. 2018). Indeed, these groups tend to act as contractors to fulfil micro-level geostrategic goals of their resource donors (DeVore 2012).

Several scholars argue that state sponsorship offers profound economic advantages for the terrorist networks, but it also can provoke terminal operational, security and financial vulnerabilities (Bauer & Levitt 2020; DeVore 2012; Eroglu 2018; Freeman 2011; Sick 2003). According to Freeman (2011), state sponsorship comes along with two main disadvantages. First, a finance-providing state may seek to control the activities of the terrorist networks. This may incapacitate the decision-making powers of the organisational leaders. Second, state sponsorship may be a ‘resource curse’ for the terrorist networks and may hold back diversification of income generation. This turns into a deadly vulnerability when the sponsoring state collapses or shifts geopolitical priorities. In this context, leadership of the terrorist networks experiences a dilemma of either enjoying the donations from foreign masters with undermined autonomy or exercising full autonomy with limited in-house financial resources (Bauer & Levitt 2020).

There is abundant literature on the involvement of terrorist organisations from different ideological backgrounds into diverse criminal activities (FATF, 2015, 2019). These criminal activities include smuggling (drugs, weapons, humans, oil, tobacco products, antiquities), extortion, robbery, racketeering and kidnapping for ransom (Clarke 2015; Ekici 2015; FATF 2015; Normark & Ranstorp 2015; Thachuk & Lal 2018). Among all the criminal enterprises, drug trafficking has been the primary financing method of Marxist and ethnic separatist organisations such as the PKK, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) (Thachuk & Lal 2018). Various international organisations reported that the radical Islamist Taliban raised millions of dollars from taxing poppy cultivation in Afghanistan (FATF 2015; UNODC 2011; World Bank & IMF 2009). Bank robberies were common among the Marxist networks in Europe and radical Islamic groups in Asia (Amicelle 2011; Ekici 2021; Horgan & Taylor 1999).

Depending on the geography, terrorist organisations may coexist with the transnational criminal networks, which may lead to different terrorism financing typologies. According to Makarenko (2004: 131) this relationship can change from ‘alliances’ to ‘convergence’ along the ‘crime-terror continuum’. According to Ekici et al. (2011) this vicious interaction brings along three main advantages to the terrorist organisations. First, they impose unit taxes on all the illegal trade materials such as heroin, cigarettes or weapons. Second, they levy annual taxes on almost all the kingpins in proportion to the scale of their income. Third, the prolonged interaction enables the terrorist networks to master the illicit trade schemes, take over the smuggling activities and eliminate the rivals on the black markets.

Many scholarly works, institutional research studies and international reports found that terrorist entities get involved in large sets of legal enterprises, such as car dealerships, real estate, restaurants and furniture trade (FATF 2015; Clarke 2015; Biersteker et al. 2008). Trade-based terrorism financing schemes have been frequently used as it is very easy to justify accumulation of capital and transfer of money to domestic and international ‘trade partners’ (Zdanowicz 2009). For instance, Al-Qaeda raised significant amounts of money from a holding company in Africa, a construction company in Sudan, ostrich farms in Kenya, Islamic banks in the Middle East, a forest business in Turkey and agricultural production in Tajikistan, Europe and the United States (Napoleoni 2006; Schneider & Caruso 2011). Several Turkish scholars also assert that the PKK has been running numerous front companies in Europe to facilitate trade-based terrorism financing (Bayraklı et al. 2019; Cengiz & Roth 2019; Ekici 2021).

Terrorist organisations seek to exploit non-profit organisations (NPOs) to generate funding and hide their clandestine activities. According to the FATF (2015, 2021), NPOs can be exploited in five different methods: i) terror entities can divert the legitimate donations via allied employees, ii) NPO authorities can be aligned with the interests of the terror networks, iii) assistance programmes can be reconfigured to support terror networks, iv) NPOs can be turned into recruitment platforms and v) sham NPOs can be established to cover up the fraud/misrepresentation in assistance programmes. Another FAFT (2014a) study found that services of the NPOs operating in close proximity to ongoing terrorist threats are more likely to be abused and humanitarian assistance programmes to bear a high risk of dispersion.

Available research revealed that especially radical Islamic networks have been exploiting charities to diversify legally collected funds into illegal activities (Bricknell 2011; Raphaeli 2003; Schneider & Caruso 2011). According to Looney (2006), wealthy Saudi sponsors abused the Islamic charities to deliver funding to Wahhabi cells in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Southeast Asia and the Middle East. Key al-Qaeda operative – and Osama Bin Laden’s brother-in-law – Mohammed Jamal Khalifa directed the International Islamic Relief Organization (IIRO) to support terrorist organisations in Southeast Asia (Croissant & Barlow 2007; Schneider & Caruso 2011).

Several research studies indicate that popular support can generate substantial amounts of financial resources for the terrorist organisations (Freeman 2011; Clarke 2015; Thachuk & Lal 2018). According to the FATF (2015), terrorist organisations deploy different strategies to harness it. First, they can impose involuntary taxes on certain ethnic or religious groups. Second, they can establish charities and non-profit organisations to encourage donations from among the communities of sympathisers. Large terror organisations (PKK, Al-Qaeda, LTTE) tend to diversify such NPO activities across different countries and sectors to reduce vulnerability to financial supply disruptions (Bell 2007; Bricknell 2011).

Diaspora communities may function as a finance multiplier for the terrorist organisations. The TF literature demonstrated that the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA), the PKK, the LTTE and Hezbollah have been benefiting from the ‘donations’ of the diaspora communities living abroad (Myres 2012; Nomark & Ranstorp 2015). According to Nomark and Ranstorp (2015), PIRA sympathisers in the US and Europe were systematically transferring funds to combatant units. The PIRA diaspora generated these funds from large sets of legal businesses, such as pubs, real estate and taxi companies along with criminal enterprises such as extortion, robbery, kidnapping for ransom and tax fraud (Myres 2012). Al-Shabab generated substantial amounts of money from Somalians working abroad (Nomark & Ranstorp 2015). The organisation relied on cash couriers and the Hawala remittance system to circumvent international AML/CFT measures. Large numbers of Kurdish businesses, non-profit organisations and criminal networks in Europe have been systematically funding PKK operatives in Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Syria (Bayraktar et al. 2019; Ekici et al. 2011). Similarly, the Sri Lankan Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) established a clandestine network to extract financial contributions from Tamil communities living abroad. According to Nomark and Ranstorp (2015), the LTTE enforced compulsory payments from diaspora businesses of up to USD 75,000 and the families were forced to pay between USD 2,000 and USD 3,700. Levitt (2005) reported that Hezbollah benefited from a complex web of diaspora communities that run large numbers of NPOs and businesses in Africa and South America.

Territorial control can be another defining factor for financing typology. In ungoverned or under-governed spaces terror networks tend to behave like mafiosa states: collecting taxes, cultivating drugs (cannabis, coca and poppy), manufacturing synthetic drugs (ATS, methamphetamine), looting historical sites and exporting natural resources (Thachuk & Lal 2018; Clarke, Bauer & Levitt 2020). Failure to comply with the economic requests of the terrorists is harshly penalised by de-facto ‘security institutions’ and ‘courts’ (Ekici 2021; Clarke 2015). Territorial control allows the networks to implement social welfare programmes, form alternative governance systems, promote their ‘legitimacy’, gain the loyalty of the local populations and wage battles against their enemies (Bauer & Levitt 2020; Freeman 2011).

Availability of natural resources has a defining impact on the terrorism financing methodology (Bauer & Levitt 2020; Farah 2004; FATF 2015). Terrorist organisations in resource-rich countries tended to exploit the smuggling of these resources into regional or global underground markets. Douglas Farah (2004) found that the smuggling of ‘blood diamonds’ in African countries has been a prevalent method of financing for different terrorist groups. According to Thachuk and Lal (2018), oil smuggling has been a primary method of terrorism financing in resource-rich countries, such as Iraq and Syria. Al-Qaeda-affiliated groups perceive foreign control of hydrocarbons as looting of national resources by a coalition of ‘corrupt’ government officials and ‘neo-imperialists’ multilateral corporations (Kancherla 2020; Scheuer 2011). Therefore, they try to control and export the hydrocarbons to third parties from the territories under their control (Kancherla 2020). However, the control of oil smuggling schemes turned out to be extremely costly for ISIL as it provoked massive military operations by the host governments and the coalition forces (Dadpay 2020; Ekici 2021; Holland-McCowan & Basra 2019).

There is a large body of literature on the money transfer systems used by the terrorist organisations. The formal banking system continues to be exploited by the terrorist networks with extreme caution: transferring money under reporting thresholds, structuring the deposits, using intermediaries to hide the beneficiary owners, using sympathisers without criminal records, and choosing locations with weak AML/CFT compliance (FATF 2015). However, many security scholars and institutions reported that alternative (informal) remittance providers (mainly Hawala) or money service businesses (MSBs) have been the most popular transfer system among the terrorist networks in the Middle East, Europe and Asia (Bunt 2007; Bauer & Levitt 2020; FATF 2015; Schneider & Caruso 2011). Money service businesses functioned as an intermediary between the modern banking systems and the cash-based local economies in the developing countries. The bulk of the MSBs and informal transfer systems has functioned outside the global AML/CFT regulatory frameworks and compliance requirements since they remain unregistered (de Bunt 2008). The prevalent use of the MSBs obfuscated the financial transactions by the transnational organised crime groups and terrorist networks. Al-Qaeda and ISIL skilfully exploited the established informal MSBs for transfer of funds. For instance, the Rawi network of hawaladars in Iraq was frequently used by the Al-Qaeda and ISIL operatives to stay off the radars of the global and regional financial intelligence units and the sanctions regime (Bauer & Levitt 2020).

Ideology can play an important role in the decision-making process of the terrorist financing (Hansen & Kainz 2007; Napoleoni 2006, 2016). If an organisation aspires for self-autonomous ideology, it will be less likely to be dependent on state sponsors that aim to control the operational activities with conditional aids (Bauer & Levitt 2020). Terrorist groups are more likely to succumb to donor demands when they have ideological admiration for the political systems of the state sponsors. For instance, Shiite groups in Iraq or Lebanon are more likely to accept state sponsorship of the Iranian regime due to ideological affiliations (Frankel 2012). On the flipside, Sunni Al-Qaeda and ISIL networks are less likely to engage in asymmetric economic relations with Iran due to drastic differences in ideological orientation (Hansen & Kainz 2007).

Ideology can also have a defining impact on justification of immoral financing methods, such as drug trafficking, kidnapping for ransom, human trafficking and prostitution. According to mainstream scholars, Islam is strictly against the production, consumption and trafficking of drugs (Ghiabi et al. 2018). ‘Islamic’ organisations are encouraged to stay out of these profitable, but immoral financing schemes. However, reinterpreted Wahhabi ideology embraced a Machiavellian principle that every method is justifiable in the war against the near enemies (local governments) and the far enemies (Western governments) (Gerges 2011; Scheuer 2011; Stern 2003). Indeed, Salafi clerics campaign for the complete overthrow of the existing moral order which ‘resembles’ the norms of pre-Islamic jahiliyya societies (Khatab 2006). Mainstream Salafi clerics, such as Sayyid Qutb and Ayman Al Zavahiri, assert that the ‘believers’ currently live in darulharp (warzones) which grants them the justification to employ extraordinary precautions that are prohibited in the darulislam (Islamic lands) (Hansen & Kainz 2007). Sayyid Qutb believed in an inevitable clash between the jahiliyya and Islam. Qutb called for joining the fight (jihad) for the global supremacy of Islam and the termination of the jahiliyya (Hansen & Kainz 2007). This justification has been used for plotting suicide bombings in the Middle East and taxing the heroin production in Afghanistan.

Marxist ideology has been embraced by many terrorist organisations in the world, such as the FARC, the LTTE, the PKK and DHKP-C (Alexander & Pluchinsky 1992; Ozgul 2014). Marx and Engels (2009) believed that the existing laws and government systems serve to the interests of the capitalist bourgeoisie class that inhumanely exploits the labour of the proletariat and resources of the developing countries. They argued that a compromise between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat is impossible. Therefore, Marx and Engels called for a revolution that would overthrow the domination of the capitalist class, eliminate private property and bring an end to exploitation of the worker class. The existential nature of this struggle leaves no room for moral or ethical principles. Marxists have been also encouraged to resort to every possible method to cast a blow to the capitalist system. According to several Turkish scholars, the PKK’s Marxist ideology provided justification for generating funds via every possible means, including drug trafficking, in the fight against the Turkish government and the wealthy feudal class in Southeastern Turkey (Akkaya 2020; Cengiz & Roth 2019; Sen 2021).

Methodology

This research project applied a comparative and qualitative methodology to understand the terrorism financing typologies in Turkey. The research has been composed of two stages. At the first stage, we reviewed relevant academic publications, international reports, institutional publications, non-classified official documents, court decisions, threat assessments, incident reports on media and secondary interviews with the experts and former members of the PKK and ISIL organisations. Throughout the desk-review process we reached out to potential experts who have first-hand experience with combating financing of terrorism.

At the second stage, we conducted 26 face-to-face interviews with the identified experts in the Ankara, Istanbul, Gaziantep and Kahramanmaras provinces between October 2020 and December 2022. Moreover, we carried out 12 online interviews (via Skype, Zoom or Microsoft Teams) with the experts who lived abroad or were not available for physical interviews due to COVID-19 restrictions. The interviewees have been selected from a diverse set of backgrounds: current or former law enforcement officers, prosecutors, judges, government officials, academics, analysts from Financial Intelligence Units (FIU) and experts from international organisations. All interviews have been conducted in a semi-structured format, which allowed for probing into individual and specific experiences. Code names have been given to each interview to prevent the interviewees from being targeted by the terrorist organisations.

Research findings on the financing of the PKK and ISIL

This research indicated that both ISIL and the PKK attempted to diversify the sources of funding through engaging in a large set of criminal and legal enterprises. The PKK has developed sustainable financing schemes as it managed to survive over four decades. The long lifespan allowed the organisation to set up advanced financial settlements in Iran, Turkey, Iraq, Syria and Europe. However, ISIL failed to develop sustainable financing infrastructure due to several reasons. First, the UN Security Council implemented a large number of sanctions on ISIL operatives and affiliated groups. The sanctions limited the influx of financial resources to the network members especially after 2017. Second, air strikes in Iraq and Syria destroyed the oil facilities, arsenals, warehouses and operational compounds of the organisation. The bulk of the ISIL resources was either destroyed or confiscated during the concerted operations of the coalition forces. Third, loss of territory undermined the taxation capacity of the ISIL leadership. Even though many ISIL members moved into other countries under the guise of ‘political refugees’, the organisation lacks sophisticated financing mechanisms. Lone wolf ISIL attacks at populous places in Turkey were all low-cost. Therefore, this research contradicts the arguments that portray ISIL as the ‘richest’ terrorist organisation (Clarke 2015; Napoleoni 2016).

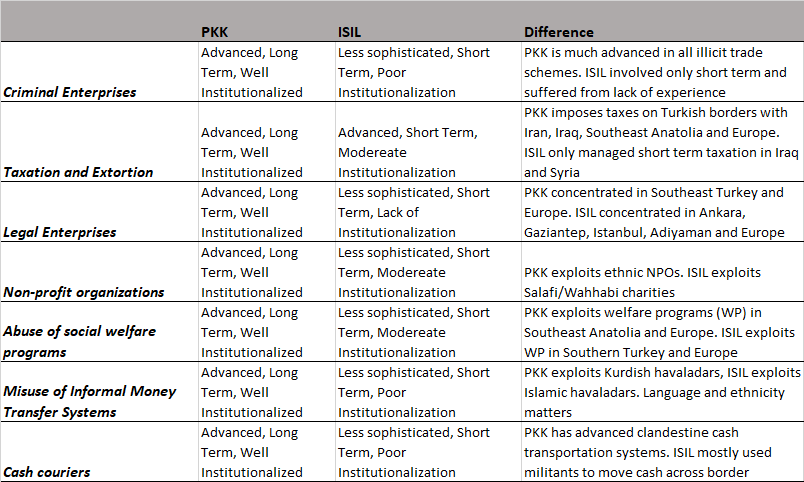

Table 1: Comparison of PKK and ISIL financing typologies

Source: Authors

The qualitative analysis of the open and axial codes revealed that state sponsorship, criminal enterprises, taxation and extortion, legal enterprises, misuse of non-profit organisations and charities, misuse of informal money transfer systems, abuse of social welfare programmes and exploitation of cash couriers have been the primary issues (axial codes) raised by the interviewed experts on terrorist financing typologies in Turkey.

Criminal enterprises

Our research indicated that regardless of ideological orientations, both the PKK and ISIL sought to exploit Turkey’s underground economy and the illicit trade with the neighbouring countries. Particularly, the collapse of the states in Iraq and Syria had tremendous collateral impacts on schemes for financing terrorism that were employed by criminal enterprises. The exponential growth of the black markets in the bordering states increased the flow of unlawful goods into the Turkish market via the Gaziantep, Sanliurfa, Hatay, Sirnak, Mardin and Hakkari provinces (Interview GA1 2020). According to the interviewee (GA4), numerous entry points along the Turkish borders with Iran, Iraq and Syria enabled infiltration by the criminal nodes of the PKK and ISIL terrorist organisations (Interview GA4 2020). Even though the PKK and ISIL came from completely different ideological backgrounds, their modus operandi in the illicit markets have been quite similar, especially in desperate situations.

The PKK as a criminal network

This research revealed that the PKK’s Marxist-Leninist ideology played a significant role in the group’s involvement in criminal enterprises. The PKK has been ideologically motivated to fight against the coalition of the Turkish State (which they saw as the spearhead of Western imperialism) and the wealthy land-owning Kurdish families that ‘oppressed’ the ‘Kurdish peasants’ and the ‘worker class’. According to the interviewee (ON3), the organisation perceived the Turkish constitution, criminal and penal laws, and tax legislations as tools of oppression and exploitation (Interview ON3 2021). Therefore, they encouraged smuggling all types of goods to circumvent taxation by the government. Even though the PKK banned the use of drugs among its members and sympathisers, the organisation made large volumes of money from all stages of the illicit drug business (Interview KA2 2021).

The PKK has a long history of engagement with criminal enterprises. Turkish, European and American government sources, international (UNODC, Interpol, FATF) reports and academic studies demonstratively documented the PKK’s involvement in criminal activities. According to interviewed Turkish security experts, the PKK played a significant role in the trafficking and smuggling of drugs, humans, oil and weapons. The organisation developed advanced systems to carry out these criminal enterprises.

There is a consensus among the interviewed security experts that the illicit drug trade has been the largest source of revenue for terrorist and organised crime groups. There are various estimates about the volume of PKK financing coming from the illicit drug trade. According to General Engin Saygun, the former deputy chief of Staff of the Turkish Armed Forces, 50 to 60 percent of the annual revenues of the PKK were generated by illicit drug business (Laçiner & Doğru 2016). According to Cengiz Erisir, the former director of the Turkish Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug addiction (TUBIM), the PKK received 1 to 3 billion US dollars from the illicit drug business annually (Laçiner & Doğru 2016).

The PKK initially developed asymmetric symbiotic relationship with notorious Kurdish drug networks, such as the Baybaşin, Canturk, Konuklu, Ay and Buldan families that were controlling the Turkish and European heroin markets (Interview ON6 2020; Interview AN30 2021). The relationship was primarily based on the economic exploitation and taxation of the heroin trafficking schemes by PKK operatives (Interview AN30 2021). Later, other substances, such as cannabis, captagon, morphine base, chemical precursors, tobacco product and petroleum products, were added to the repertoire of trafficking. Various interviewees indicated that the PKK has been the strongest organised crime establishment in Turkey, which maintained its criminal activities for decades (Interview ON1 2020). The PKK’s involvement in drugs increased qualitatively and quantitatively after the 1980s. The organisation gradually took control over illicit trade in Turkey’s southeastern parts that border with Iran and Iraq.

The investigation files of Turkish law enforcement indicated that the PKK has been involved in several stages of the illicit drug trade (Ministry of Interior 2017). According to the Ministry, the first engagement took place in the Beqaa Valley (Lebanon) when they escaped from military crackdown on 12 September 1980. In partnership with the Palestinian networks, PKK leadership cultivated cannabis and used the money to purchase weapons from international traffickers. During the early 1980s, PKK operatives produced around 60 tons of drugs in the Beqaa Valley annually (Interview ON2 2020). Drug money was a lifesaver for the organisation which was suffering a severe financial crisis due to extreme security measures put in place after the military coup of 1980. After the crackdown ended in 1985, the PKK gradually moved to cultivate cannabis in Southeastern Turkey, where it employed large numbers of Kurdish peasants for the industry (Interview D1 2011).

Several tons of cannabis resin, marihuana and cannabis seeds were seised at PKK shelters and safe houses by Turkish security forces. Seizure of the seeds and statements of arrested individuals clearly demonstrated that the PKK actively engaged in spreading cannabis cultivation in Southeastern Turkey (Interview ON4 2021). According to a former police chief in the city of Lice of Diyarbakir Province, many convicted cannabis growers stated that the seeds were originally introduced to the region by PKK operatives (Interview ON4 2021). The organisation delivered seeds during the planting season and reappeared at the harvesting period to collect the taxes. Occasionally PKK operatives controlled the transportation of cannabis to consumption markets in Ankara, Istanbul, Izmir, Adana, Mersin and other large cities in Turkey. Some experts believe that the PKK channelled the money from cannabis business to the construction of apartment complexes in Hakkari, Diyarbakir, İzmir, İstanbul and many other provinces (Interview AN26 2021). A statement by the interviewee (ON4), clearly illustrate the scale of cannabis business in Diyarbakir Province:

There are endless cannabis fields in Northern towns Lice, Hazro and Kulp [of Diyarbakir]. Cannabis is grown in 80 villages where Gendarmerie rarely visits. Only this year the production is estimated to be over 500 tons. The entire production is made under the supervision of the PKK. It is impossible to plant cannabis without paying taxes to the organization. Cannabis fields are burned if they try to do so. Only last year their income from these three towns was estimated to be over 50 million dollars. . . . The money goes to Kandil via jewelers or other large business owners in Amed [Diyarbakir]. Police and Gendarmerie seize only a fraction of what is produced. The rest of the cannabis goes to big cities, like Istanbul, to poison the youth (Interview ON4 2021).

The PKK has been playing a significant role in the production and trafficking of heroin along the Balkan route. Indeed, the organisation sought to eliminate intermediary organisations to widen the profit margin. The heroin trafficking makes several folds profits on its way from Turkey’s border with Iran to Western Europe without the intermediaries (Interview ON7 2021). According to the Department of Anti-Smuggling and Organized Crime (KOM) (2005), the PKK organisation runs countless heroin labs on the Turkish-Iranian border. More than 20 heroin labs under PKK-affiliated individuals were dismantled in various provinces of Turkey (mainly Hakkari, Van and Istanbul). The precursors have been procured from Russian, Eastern European and Iranian suppliers. The KOM report in 2005 highlighted that joint operations of the KOM-DEA presented solid evidence of the PKK’s precursor supply chain originating in Russia (KOM 2005). Once the heroin is produced in Northwestern Iran or Southeastern Turkey, it is transported to the warehouses in Western Turkey. The PKK either transports the heroin by specially deployed cells or it levies taxes on the transnational crime syndicates that take over the transportation process from Eastern Turkey (Interview D1 2011).

Some interviewees draw attention to the arrests of PKK operatives by the European law enforcement agencies for wholesale heroin trafficking (Interview ON2 2020). For instance, Murat Cernit, the PKK’s top operative in Moldova, was arrested with 200 kg of heroin as a result of a joint operation of Turkish, Moldovan and American counter-narcotics units (Interview ON2 2020). The US Department of Treasury placed PKK members Murat Cernit, Zeynettin Geleri and Ömer Boztepe on the OFAC list (US Department of Treasury 2022).

According to senior police officials, PKK operatives and sympathisers played a significant role in the distribution of drugs in metropolitan Turkish cities, such as Istanbul, Ankara, Izmir, Adana and Mersin. For instance, Mustafa Çalışkan (2019), former police commissioner of Istanbul, reported that police units arrested 30 PKK members in 12 cases of poly-drug distribution in Istanbul between 2016 and 2018. Çalışkan emphasised that PKK members were cooperating with the other distribution networks in cafes, restaurants, tea gardens and fast-food chains. The organisation used these locations to connect with potential sympathisers and new recruits.

Human smuggling and trafficking have been a significant source of revenue for transnational crime syndicates and terrorist networks. Turkey has been exposed to large flows of illegal immigrants from Southwest Asia and the Middle East. The research indicated that the PKK has been smuggling individuals across Turkey’s eastern, southern and western borders (Interview ON1 2021). The PKK uses extensive clandestine networks to facilitate the transportation of individuals and groups. The PKK imposes taxes on the human smugglers that cross the mountainous terrains along Turkey’s borders with Iraq and Iran. The amount of taxation ranges between USD 2,000 and USD 8,000 in accordance with the associated risks, border location and target country (Interview ON3 2021).

However, not all the human-smuggling schemes were profit-oriented. The PKK smuggled out thousands of operatives and sympathisers that were on the watchlist of the Turkish security institutions (Interview AN34 2021). These individuals were gradually moved to refugee camps to start the asylum procedures. In partnership with the HDP representatives, the PKK smuggled Kurdish children to be trained and deployed at terror compounds in Iran, Iraq, Syria and Europe, especially during the ‘peace process’ According to the interviewee, the PKK engaged in the forgery of passports and national ID documents to facilitate illegal border crossings. Over the years, the PKK was able to establish a large number of civil society organisations in Europe that functioned as financing and propaganda tools for the leadership (Interview GA4 2020). Once the immigrants arrive in Europe, the PKK registers them in one of the Kurdish Associations to fulfil the official procedures for refugee status. The PKK’s financial apparatus provides food and shelter until the Kurdish immigrants are granted refugee status and able to apply for legal jobs.

Since the early 1980s, the PKK has forged a partnership with the smugglers of small arms and light weapons (SALW). The organisation needed a constant supply of rifles, pistols, rocket launches, mines and ammunition. Interviewed experts noted that the PKK was able to procure weapons from a diverse set of organised crime groups. Bulgarian, Czechoslovakian, Yugoslavian and Soviet intelligence establishments sub-contracted criminal networks to supply SALW to the PKK and other Marxist terrorist networks (Interview ON5 2021). However, there is no strong evidence that the PKK was involved in the systematic and prolonged trafficking of SALW to generate funds.

This research found that the smuggling of natural resources has been a key income for the terrorist organisations regardless of their ideology. Turkey is not a resource-rich country, but it is surrounded by major hydrocarbon exporters, such as Iran, Iraq, Syria and Russia. According to the Global Petrol Prices website (2020), the price of gasoline is USD 0.91 in Turkey, USD 0.06 in Iran and USD 0.63 in Iraq as of 31 August 2020. The oil barrel price is USD 10.32 in Iran and USD 100.11 in Iraq and USD 144.37 in Turkey. These figures indicate that there is a 14-fold profit opportunity for the oil smugglers operating on the Turkish-Iranian markets. Terrorists and transnational criminal networks frequently steal the oil from state pipelines and wells. As one interviewee put it succinctly, there is always a demand for cheap oil in Turkey and this demand is met by a complex set of actors, including terrorist networks (Interview ON3 2021). The field research indicated that the PKK exploits the oil smuggling along Turkey’s borders with Iran and Iraq. The PKK levies taxes on the motor and animal-powered transport carrying illicit oil to the Turkish market.

Turkey has a large illicit market of cigarettes due mainly to over-taxation of tobacco products. According to Mehmet Eryilmaz (2013), a former chief inspector at Turkish Customs, illicit supply constitutes 20% of the overall domestic cigarette market. The PKK’s criminal establishment smuggles contraband cigarettes into the Turkish and Iraqi markets (Interview AN34 2021). Moreover, illegal taxation units at the mountainous borderlines impose taxes on all cigarette smugglers who seek entrance to profitable Turkish black markets.

ISIL as a criminal network

Wahhabi/Salafi groups perceive the regional governments as tağuts (oppressive regimes) and the secular laws and international conventions as ‘illegitimate’ dictates of jahiliyya (Interview GA7 2020). Members of these groups are strongly encouraged to involve in jihad to bring into force the Sharia laws, ‘which will end the economic exploitation of the Muslim societies’ (Interview GA7 2020). However, until this aim is accomplished, members can employ takiyya, which means pretending to be law-abiding citizens in darulharp zones. Very similar to the PKK, Salafi groups seek to circumvent secular tax laws and encourage smuggling not only to generate funds but also to avoid financing the ‘oppressive regimes’.

This research found that the ISIL is more involved in criminal enterprises in Turkey than its predecessor Al-Qaeda. ISIL operatives have been extensively present and active in trafficking oil, drugs and antiquities. These illicit goods predominantly originate in ISIL controlled areas in Iraq and Syria. Turkey has been a significant market for the illegal merchandises imported from the ISIL territories. Once the illicit goods are sold in Turkey, the proceeds are mostly transported back to Syria via cash couriers (Interview GA18 2020).

Wahhabi groups have been strongly against ‘exploitation’ of the regional energy sources by multinational corporations. For them, ISIL became the ‘legitimate’ rulers of the hydrocarbon resources as they took over Iraqi-Syrian territories. They never perceived oil exports as ‘smuggling schemes’ but the ‘rightful trade of the real owners of those lands’ (Interview GA4 2020).

ISIL leaders hoped to earn substantial amounts of money from the looted hydrocarbon fields. However, the organisation lacked the legitimacy, economic connections and the experience to export the resources in highly interconnected global energy markets since the international energy companies suspended their operations in ISIL controlled territories. ISIL responded by re-deploying former petroleum engineers at state companies and even paying higher salaries than the Iraqi and Syrian governments (Interview GA1 2020). The group also captured the refineries and transportation lines to potential markets of the confiscated hydrocarbons. Smuggling, then, appeared to be the only solution to generate funds to finance the brutal campaigns (Interview GA1 2020).

Turkey has been the most profitable regional market for illicit oil with high demand and high prices. Oil sales at the black market continued to grow exponentially due to the extreme taxation policy with regards to energy products (Interview GA18 2020). Interviewed experts are in consensus that the largest portion of ISIL gasoline entered Turkey. ISIL cut down the price of oil to be more competitive at the Turkish underground market. They quickly forged partnerships with intermediaries and transnational criminal networks for distribution of gasoline. However, there are no publicly available criminal prosecution files that document how this trans-border illicit trade was facilitated by a diverse set of actors (Interview GA2 2020). Moreover, there is only superficial information on the identities of Turkish intermediaries involved in the clandestine oil trade.

The resource boom and financial euphoria did not last long for the ISIL leadership. The US surgical air strikes and subsequent military operations nullified their control over Syrian and Iraqi energy resources. These strikes played a significant role in disrupting the supply chain of illicit oil trade between Syria and Turkey (Interview GA20 2020). The potential revenue from the control of energy resources dried up to a great extent for the terror organisation. On the Turkish side of the border, air strikes against the tankers were never considered an option. Turkish law enforcement agencies arrested many oil smugglers but the oil smuggling schemes between ISIL controlled areas and Turkish criminal networks need further assessment (Interview GA20 2020).

Kidnapping for ransom (KFR) was a significant source of revenue for ISIL in Iraq and Syria. The FATF (2015) reported that ISIL operatives requested ransoms ranging from EUR 600,000 to EUR 8 million for each kidnapped individual. The FATF estimated that 5–50% of the annual revenue of the organisation came from this activity. Statements of Turkish experts confirm the FATF reports on ISIL’s KFR activities. One expert noted that ISIL formed an ‘intelligence apparatus’ in the region to determine the targets of kidnapping operations for political and economic reasons (Interview GA14 2020). This apparatus allowed them to identify large sets of vulnerable individuals such as Western journalists, Assyrian Christians, truck drivers and diplomats.

As one interviewee put it succinctly, ISIL used kidnapping to gain bargaining power with the other states (Interview GA14 2020). For instance, ISIL attacked Turkey’s Mosul Consulate in June 2014 and kidnapped 49 Turkish diplomats and consulate staff. The hostages were released after the parties (Turkish Government and ISIL leadership) reached an agreement for exchanging the consulate staff with 180 arrested ISIL operatives. Moreover, ISIL kidnapped a large number of Turkish truck drivers for different purposes. In June 2014, 32 Turkish truck drivers were kidnapped in Mosul by ISIL control units. These drivers were released 23 days after the kidnapping incident occurred. Nevertheless, not all the truck drivers were lucky. Many drivers who failed to pass the ‘religious test’ were executed. ISIL burned large numbers of Turkish trucks at road checks.

Some security analysts indicated that the looting of antiquities was a major source of revenue for ISIL (Interview GA4 2020). The organisation controlled 2,500 historic sites in Iraq and 4,500 sites in Syria at the peak of its power (Center for Analysis of Terrorism, 2016). ISIL operatives generated significant revenues from antiquities business in several respects. First, the organisation issued permits for excavations at archaeological sites. Second, looters were taxed in accordance with the value of found artifacts. Third, ISIL operatives actively engaged in excavation of the historical artifacts with their own machinery and equipment. Fourth, ISIL smuggled the artifacts to potential markets, including Turkey and Europe.

The artifacts stolen from the museums, storage locations, historical sites and private collectors were then transported across the border. ISIL has sold large numbers of cultural properties to intermediaries in Turkey (Interview GA18 2020). According to the interviewee, at the beginning, ISIL depended on Turkish brokers to market the stolen artifacts, but later the organisation established connections with dealers in Europe, particularly British collectors. This argument has been substantiated by international researchers. For instance, Daniela Deane (2015) reported that ISIL was able to smuggle nearly 100 Syrian artifacts to Britain, which included pieces from the Byzantine and Roman eras. Direct connections to the antiquities market in London dramatically increased the profit range for the terror organisation. Even though artifacts generated a short-term boost to the ISIL budget, it is not a long-term sustainable source of revenue due to the scarcity of goods.

Turkish authorities report increasing involvement of human traffickers of Arabic origin who have facilitated the transborder movements between Turkey and the EU. The role of ISIL in trafficking Yazidi women is well documented in Iraq and Syria, but the Turkish side remains controversial. In 2015, the Northern German Broadcasting (NDR) channel broadcasted a video documenting that ISIL established slave brokers in Gaziantep to facilitate trade of captured Yazidi women. According to the NDR (2015), ISIL brokers used a local office to negotiate with the potential customers and handle large sums of money. Local law enforcement units raided the business centre where the alleged trade took place. In Gaziantep, police seised 370,000 US dollars, many foreign passports and 1768 pages of money transaction documents in Arabic (Ekici 2021). The Gaziantep Heavy Penalties Court launched an adjudication process with charges of financing terrorism and being an ISIL member. Investigations revealed that the network used the informal money transmittance systems through jewellers and exchange offices. Arrested individuals claimed that they wired the money through informal mechanisms due to the collapse of the formal banking system in Syria. The case was closed due to ‘lack of evidence’ for the sale of Yazidi sex slaves in Turkey.

Some analysts noted that ISIL facilitates human smuggling or trafficking via the Mediterranean Sea (Interview GA19 2020; Interview AN24 2021). For them, ISIL imposed heavy taxes (50%) on the boats sailing along the Mediterranean route. Media content analysis revealed large numbers of incidents with involvement of Syrians in human trafficking schemes. However, it is not clear whether the Syrian human traffickers act on behalf of ISIL leadership. There is no intelligence or law enforcement threat assessment reports on ISIL’s systematic involvement in human trafficking schemes.

International sources shed important light on ISIL engagement with drug trafficking. According to some international researchers, ISIL benefited from the cannabis trafficking from Iraq and Syria to Europe via Turkey (Clarke 2015). Turkish authorities did not confirm trafficking of cannabis by the network members, but they reported arrests of ISIL operatives on grounds of heroin distribution. According to the Ministry of Interior (2017), Turkish counter-narcotics units seised 167 grams of heroin from ISIL members in Konya province in 2017. Similarly, Iraqi authorities reported that ISIL ran heroin laboratories at Musul University and other locations (Lal 2018). According to Iraqi sources, ISIL deployed Afghan individuals who had extensive experience in heroin manufacturing. Turkey has been the primary transit destination of heroin produced in Northern Iran. Rollie Lal claims that ‘heroin from Afghanistan and Da’esh controlled regions is often transported through Iran into Turkey’ (2018: 54).

Italian authorities discovered a drug trafficking scheme extending from Libya and Egypt to Europe. The scheme was coordinated by a network of ISIL operatives extending from Iraq and Syria to Europe via Libya and Egypt (Paoli & Bellasio 2017). Italian law enforcement also reported seising over 280 tons of hashish headed for the Balkans region through Libya and Egypt. Experts believe that these maritime vessels were taxed by ISIL operatives (Lal 2018). Spanish police seised around 20 tons of cannabis in a ship which was destined from Turkey to Libya in October 2016. Police investigations revealed that Syrian nationals were linked to Moroccan and Spanish networks. Drugs and weapons were carried in the boats interchangeably (The Middle East Eye 2016).

One interviewee emphasised that ISIL operatives used amphetamine type stimulants (ATS) to relieve pain and gain resistance and courage for fearsome battles with adversaries (Interview KA2 2021). Captagon became the notorious ‘jihad pills’ and was widely used by ISIL operatives during armed clashes. Turkey is an important production, transit and consumption market for the ATS, mainly captagon tablets. Former counter-narcotics officials reported a significant increase in captagon seizures since the inception of the Syrian conflict (Interview ON2 2020).

ISIL used forged passports and documents extensively to facilitate movement of fighters between Europe, Turkey and the Middle East. Daily Mail reporter Nick Fagge traced the passport forgery process along this line. According to Burford (2017), ISIL fighters were systematically using forged documents to penetrate into Europe. Passport forgery allowed them to wipe off their criminal records and possibilities of arrest along the route. Fagge highlighted that the passports, ID cards and drivers’ licenses were originally stolen from government officials on dead people, and ISIL changes the pictures on the original documents. Fagge was able to buy himself a Syrian passport for USD 2,000 in Turkey and had it ready four days after he paid.

ISIL operatives stole large numbers of pickup trucks (mainly Toyota Hilux) and SUVs from a diverse set of countries. Quite interestingly, vehicle theft schemes were even reported by Canadian and Australian authorities. Some of these vehicles were transported to Syria via the territory of Turkey to be used in the jihad against the coalition forces (Interview GA2 2020).

Taxation and extortion

Extortion has been a significant source of revenue for both PKK and ISIL entities. The PKK has been extorting Kurdish businessmen throughout Turkey and Europe. Some of these ‘businessmen’ were Kurdish drug traffickers who gained enormous wealth with their extensive clandestine networks. Similarly, ISIL implemented extensive extortion schemes in Syria and Iraq. According to the FATF (2015), ISIL placed a 50% tax on the salaries of government employees who lived in the territories under their control. ISIL also imposed taxes on the local communities for movement of goods, trade activities, cash withdrawals from banks, vehicles and even for school registration for the students (FATF 2015). However, our interviews indicated that ISIL has not been able to implement comprehensive taxation and extortion schemes in Turkey.

The PKK’s taxation and extortion schemes

Over the years, the PKK has developed an advanced economic intelligence network in the Middle East, Turkey and Europe. The third congress in Lebanon (1986) was a turning point for the financial strategy of the PKK leadership, where they decided to impose taxes on the sympathisers, business owners, traffickers and organised crime groups. As the interviewee reported, the organisation monitored regional licit and illicit economic activities and the salaries of sympathisers (Interview ON3 2021). The financial apparatus of the PKK levied taxes proportionally to the monthly and annual earnings of the individuals and companies.

This research revealed that the PKK’s taxation and extortion policy has been implemented in several ways. First, the PKK has been coexisting with trans-border traffickers in Southeastern Turkey, Northern Iraq and Northwestern Iran. The organisation established de-facto customs check points at Turkey’s borders with Iran and Iraq. According to the interviewee, who previously served at the PKK taxation units on the Turkish-Iranian border, traffickers have been taxed in accordance with the type and amount of the substance (Interview D1 2011). Thousands of arrested traffickers gave statements regarding this illegal taxation. Taxation receipts with PKK (or the People’s Defence Forces, HPG) stamps were found during body and vehicle searches. According to the available evidence from law enforcement investigations, the PKK imposes a 10% tax on the drug traffickers and cigarette smugglers along Turkish-Iranian borders (Interview ON3 2021). Human traffickers have also been systematically taxed at illegal border crossings. Illegal immigrants who don’t have the money to pay the PKK border units are reportedly beaten and female immigrants are raped (Interview ON3 2021).

Second, the PKK’s intelligence units monitor the incomes and properties of Kurdish businessmen profiting from licit and illicit trade. For instance, in the Hakkari, Diyarbakir, Van, Şırnak and Mardin provinces, the PKK imposed annual ‘patriotic taxes’ on heroin kingpins (Interview AN26 2021). Content analysis of the statements of arrested drug lords indicated that the annual taxation eventually went up to several million dollars (see Pek & Ekici 2007). Many of these kingpins moved to Istanbul to avoid PKK pressure and develop better connections with the wholesale heroin markets in Europe.

Table 2: PKK taxation on different materials

|

Unit |

Location |

Amount |

|

Heroin (by vehicles and horses) |

Turkey's borders with Iran, Iraq |

10% |

|

Tobacco (Per horse) |

Turkey's borders with Iran, Iraq |

$3 |

|

Illegal immigrants (per person) |

Turkey's borders with Iran, Iraq |

$800-1000 |

|

Illegal immigrants (per person) |

Turkish-European Border |

$8.000-10,000 |

Source: Interviews with security experts

The PKK’s taxation policy has been extended over the legal businesses in Southeastern Turkey. During the ‘Peace Process’, KCK and HDP members visited local shop owners and requested taxes on behalf of the PKK (Interview GA4 2020). Non-compliant businessmen were kidnapped and tortured based on the trials at de-facto PKK courts in rural parts of Southeastern Turkey (Interview AN7 2020). The taxation has not been limited to the shop owners but it extended over the entire Kurdish-populated cities and Kurdish neighbourhoods in metropolitan cities. One interviewee described the taxation as following:

When I was there [in Southeastern Turkey], we learned that PKK militants were supplying daily needs from nearby villages and towns. Every farmer and business owner were forced to contribute in accordance with the type of their activities and size of their incomes. For instance, restaurant owners were forced to provide food for special activities, militants, and the families of deceased PKK members. Owners of gas stations refilled the tanks to be used at rural PKK camps. Grocery shops were asked to provide vegetables and fruits. Bakery shops supplied their breads. So, all their daily needs were met for free by the local people. Even the shop owners who seemed very close to the state provided what the PKK asked for (Interview ON3 2021).

There is abundant investigative evidence on the PKK’s collection of revolutionary taxes from the wealthy Kurdish businessmen. This taxation takes place in Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Syria and Europe. A former member of the PKK noted that the PKK’s intelligence units collected economic indicators on the potential incomes of businessmen within their neighbourhood. According to the interviewee, an amount of tax is determined for each businessperson at the PKK’s local board meetings (Interview D1 2011). Then the PKK sends a representative with a ‘sealed letter’ from the armed wing of the organisation (HPG). The letter demonstrates the requested amount, period and method of payment. Failure to pay the requested amount usually leads to kidnapping and trial at illegal self-proclaimed PKK courts. Once the businessman is kidnapped, the PKK contacts the family of the person and requests a particular amount of payment to be wired in the desired way (Interview ON1 2020). Kurdish people know that the PKK escalates the punishment measures until the payment is received. In many cases, the PKK burned the construction machines of the contractors who failed to pay the ransom. Only in rare occasions were the businessmen able to stand firm, but punishment often escalated to the point of murdering the target. For instance, the PKK killed the owners of the CKP Construction Company for failing to pay the requested amount of ransom (Ozdemir & Pekgozlu 2012). The murder took place in Istanbul far away from the construction site. The businessmen usually try to avoid any conflict with PKK operatives as they are highly aware and afraid of the PKK punishment methods. Kidnapped businessmen are released once the PKK receives the requested payment.

The PKK often used other affiliated networks, such as the HPG and the HDP, for taxation and extortion. The Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) is a ‘legal’ political party which campaigns for the rights and interests of Kurdish minorities in Turkey. As of January 2023, the party has 56 seats at the Turkish Grand Assembly. However, many senior government officials, judges, prosecutors and security experts believe that the party has been highly infiltrated by PKK operatives. According to the Attorney General’s office of the Supreme Court (2021), the PKK sought to create an ‘alternative governance system’ in Southeastern Turkey using HDP-governed municipalities as proxies. According to the prosecution office, the organisation generated significant funds from these municipalities in several ways. First, the PKK imposed a 10% tax on the salaries of the workers on a monthly basis. The money was collected in cash and no traces of the transactions were left behind. Second, the PKK imposed taxes on the companies that were awarded municipal tenders. Companies were forced to pay a significant tribute to the PKK after each contract. Moreover, the PKK coerced the mayors to render the contracts to affiliated companies. Third, the PKK used the machinery and vehicles of the municipalities for its social programmes. At the funerals of PKK militants, municipal vehicles were used for transportation. Mayors organised parades for PKK militants with municipal budgets. As a tribute, relatives of the killed terrorists were employed at the municipalities.

The PKK’s taxation and extortion of the businessmen extended to Europe. Lieutenant Colonel Abdulkadir Onay noted that

two PKK members were arrested in France in 2006 for money laundering aimed at financing of terrorism. At the end of 2005, three members of the PKK were arrested in Belgium and another one in Germany suspected of financing the PKK. In Belgium, the authorities seised receipt booklets indicating that the arrested suspects were collecting ‘tax’ from their fellow countrymen (Onay 2008: 1).

Philip Wittrock (2008) reported that the PKK collects millions of euros from the sympathisers and donors to finance their fight for the ‘freedom’ of the Kurdish ethnic groups. Based on the information from German domestic intelligence agencies, Wittrock asserted that

the organisation usually demands that its supporters donate one month's wages per year, and those unwilling to cough up are expressly reminded that they must pay this ‘tax’. It is uncertain where exactly this money then goes. The lion's share is assumed to be funeled towards the movement's European institutions and its extensive propaganda apparatus (Wittrock 2008).

ISIL’s taxation and extortion schemes

Once ISIL started to control significant portions of land in Iraq and Syria, the organisation immediately imposed taxes as if it was a legitimate state. There is abundant evidence on ISIL ‘road taxation’ in Syria and Iraq. According to the FATF (2015), the taxation was a cover-up name for comprehensive protection rackets. Brisard and Martinez estimated that ISIL earned around USD 360 million annually through taxation and extortion from the areas it controlled. According to Loretta Napoleoni (2016), ISIL taxation of human flow across the Turkish border reached an estimate of a half a million dollars in summer 2015.

The ISIL taxation policy in Iraq and Syria was implemented in several ways. First, the organisation set up checkpoints around the borders. Drivers had to go through these checkpoints and pay varying amounts of taxes, which ranged from USD 200 to USD 1,000 (Eroglu 2018). Second, ISIL imposed business taxes on all shops that sell a wide range of goods from electronics to pharmacy and farming products. The shops were also forced to pay zakat taxes to the ISIL operatives. Third, ISIL imposed utilities tax on water, electricity and communications. Fourth, ISIL imposed protection tax jizyah on ethnic minorities, such as Christians and Yazidis (Ahram 2015).

However, this field research revealed that ISIL members were not able to impose a similar taxation and extortion policy in Turkey as the organisation does not control any territory (Interview AN10 2020). Currently ISIL members try to keep a low profile and avoid committing any offences that may draw the attention of Turkish law enforcement and intelligence organisations (Interview AN14 2020). This compels the organisation to lone wolf low-budget attacks to largely populated areas in metropolitan cities.

Legal enterprises

Interviewed experts noted that both the PKK and ISIL have been involved in large sets of legal enterprises, such as car dealerships, bookstores, real estate, restaurants and furniture trade in Turkey and Europe. Several interviewees asserted that the PKK has been running numerous front companies in Europe and Southeast Turkey to facilitate trade-based financing of terrorism (Interview ON7 2021). ISIL-affiliated Salafi groups, on the other hand, have been running bookstores, teahouses and clothing stores in the Ankara, Konya, Istanbul, Adıyaman and Gaziantep provinces (Interview AN10 2020). The interviews showed that large numbers of businesses, including jewellers, exchange offices, furniture shops, supermarkets, electronic stores and restaurants located in Southeastern Anatolia, have been owned by PKK sympathisers. These businesses have sophisticated trade relationships not only with Turkish metropolitan cities, such as Istanbul, Ankara, Mersin, Adana and Izmir, but also with neighbouring countries that have large Kurdish populations. Beyond paying taxes to the PKK, these businesses have been facilitating the movement of people, money and goods between Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria (Interview D1 2011). As another interviewee (ON1) noted, legal enterprises in Kurdish dominated cities were controlled by PKK operatives during the ‘Peace Process’:

The peace process allowed the PKK to exert more influence on the shop owners. . . . We learned that the PKK operatives were visiting the houses of shop owners during the nights. Throughout the Kobani protests we saw that all shops were closed in the city by the order of the PKK. Whenever there were funerals of PKK militants, shops were also ordered to close. They [shop owners] are fully aware of the consequences of disobedience and act in accordance with the balances of fear logic. It is not easy to live there. Everyone knows that the state can put them in prison for a few years, but the PKK not only can kill them but also can terminate their entire families with torture (Interview ON1 2020).

The booming construction industry in Turkey has often been associated with money laundering and corruption. Some interviewed experts noted that in Southeastern provinces, mainly Diyarbakır, Van, and Hakkari, PKK sympathisers and members involved in illicit trade schemes (mainly drug production and trafficking) were heavily investing in the construction business. According to one interviewee, the bulk of the contractors was paying project-based tributes to PKK operatives. In this context, construction projects created not only a stream of revenue for PKK operations but also established a large number of potential safe heavens (Interview ON4 2021).

Europe-based businesses have been a core pillar of the PKK’s financing campaigns since the 1980s. In Germany, Netherlands, France, UK and Spain, PKK operatives and sympathisers run various legal enterprises, such as restaurants, grocery shops and supermarkets. One interviewee noted that the PKK established the Kurdish Businessmen Association (KARSAZ) to monitor and control the financial activities of the affiliated companies in Europe. According to the interviewee, the KARSAZ has also been a platform for laundering the proceeds of predicate offences, mainly drug trafficking (Interview ON8 2021). The PKK imposes ‘patriotic taxes’ on the salaries of the employees in Kurdish companies in Europe. The collected funds have been primarily sent to the PKK camps in Iraq, Iran and Syria via cash couriers and money service businesses.

Salafi groups run large numbers of bookstores, tea shops, supermarkets, groceries, restaurants and clothing stores in the Ankara, Istanbul, Konya, Gaziantep and Adıyaman provinces (Interview AN16 2020). ISIL was especially well-organised at religious bookstores and teahouses around the Gaziantep province and the Hacibayram district in Ankara, where the research team conducted a series of interviews. These stores were used for indoctrination, radicalisation and collection of financing for jihadist movements. Even though none of these businesses has a substantially high turnover, a donation campaign can provide sufficient resources to carry out a terror attack.

Syrian refugees have opened numerous businesses in Turkey after 2011 and, thus, have become a significant actor in the Turkish economy. According to Euronews, Syrians opened 6,589 companies which employ around 100,000 individuals in Turkey (Yagci 2018). The total turnover of the Syrian companies reached 179 million Turkish liras. Syrian business owners voiced their unwillingness to return to Syria and expressed a desire to become Turkish citizens due to the more favourable economic environment in the country. Several counter-terrorism investigations in Gaziantep revealed that Syrian businesses were sheltering ISIL militants as employees (Interview GA2 2020). However, there is a strong need for a comprehensive threat assessment study on potential risks of financing of terrorism posed by the Syrian-owned businesses in Turkey.

Non-profit organisations and charities

The PKK ideologues presented the movement as a ‘Kurdish Enlightenment’ based on Marxist doctrine and a revolt against the Turkish and Islamic domination in Southeastern Turkey (Interview ON8 2021). According to the interviewee (ON8), the ideological orientation of the PKK is incompatible with the practice of religious charities. The bulk of PKK operatives came from grassroots Kurdish families who have been living in impoverished conditions. They detested the rich Kurdish landowners who had developed feudal relations with the Turkish state since the era of the Ottoman Empire. In this context, charities have not been a common financing practice for the PKK. Instead, the organisation tried to appeal to the ethnic sentiments while collecting donations from the Kurdish communities via NPOs.

The PKK has managed to establish many civil society organisations in the European Union to coordinate political and economic activities. Bayraklı et al. (2019) found that there are 563 PKK-affiliated civil society organisations in Europe. These NPOs function as a public diplomacy tool for the PKK to organise events, make publications, deliver media broadcasts, concerts and protests. Non-profit organisations also raise funds from PKK sympathisers, affiliated businesses and foreign donors. The funding from the European civil society organisations functioned as a lifesaver for the PKK especially throughout the troubled years in the immediate aftermath of the Cold War (Interview ON8 2021). These NPOs have been hierarchically and financially connected to the PKK’s European leadership. The PKK seeks to monopolise the civil-society arena by eliminating other Kurdish NPOs (Interview ON8 2021).

Jihadist networks, mainly Salafis, have been adept at exploiting Islamic charities in Turkey since the 1990s. According to a report released by the Istanbul Police Department (IPD), the number of Salafis increased to 20,000 in Turkey (Saymaz 2021). The IPD report noted that Salafi groups are concentrated in the Konya, Ankara, Adana, Istanbul and Gaziantep provinces. The Salafi groups are organised around civil society organisations (dernekler) to gain legal status. According to a recent estimate by the Islamic scholar Ahmet Mahmut Ünlü, there are around 2,000 Salafi NPOs in Turkey and members of these organisations are armed with pump-action shotguns (Erdem 2022). Based on extensive interviews, we have found that ISIL financing schemes have been organised by civil society organisations in Ankara, Istanbul, Konya, Gaziantep and Adıyaman. These organisations collected charities for the wars in Iraq and Syria. There is abundant evidence that they collected donations from radicalised communities in Turkey. More importantly, these NPOs provided logistics and facilitated transfer of new recruits (both Turks and internationals) to the ISIL camps in neighbouring countries (Interview AN10 2020).

Both ISIL and the PKK have been skilfully exploiting crowdfunding via social media and encrypted communication platforms to generate revenue from a larger number of potential online sponsors and sympathisers. According to the interviewee, PKK operatives in Europe have been collecting donations via social media campaigns (Interview ON8 2021). Even though the UN sanctions regime placed key ISIL members under strict control, large numbers of other jihadists in Europe and the Middle East continued their crowdfunding activities. ISIL members and sympathisers communicated via secret chat rooms in the application Telegram to collect money. These funds were transferred to potential jihadists via different remittance systems. Western Union was frequently used to transfer money to the Turkish border provinces.

Abuse of social welfare programmes

Many government officials in Turkey believe that humanitarian assistance programmes have been exploited by ISIL members to finance their networks. According to the Ministry of Interior, there are 143 humanitarian associations operating in the near proximity to the Turkish-Syrian border (Hacaloğlu 2017). Turkish Minister of Interior Suleyman Soylu claimed that the international aid organisations function as ‘agents’ of foreign intelligence agencies that finance anti-state groups and deploy individuals who target the national security of Turkey (Hacaloğlu 2017).

Many ISIL members have immigrated to Europe, where social welfare programmes are comparatively better. Families with children receive enough money to live without economic desperation. Some analysts claim that ISIL operatives use social welfare programmes for terrorist financing (Nomark & Ranstorp 2015a). There is evidence that European social welfare funds were transferred to Syria via Turkey to be used in terrorist activities. Belgian authorities investigated 29 sympathisers under social welfare programmes and found that they were not living at the registered addresses (Ranstorp 2016). According to Ranstorp (2016), these fighters accessed their accounts to withdraw cash around the Turkish border with Syria.

Even though the EU enlisted the PKK as a terrorist group in 2002, its focus has gradually deescalated in recent years. Some experts highlighted that the PKK exploits the EU humanitarian assistance programmes for civil society organisations (Interview ON8 2021). According to a former risk manager at a European humanitarian organisation, the support to Kurdish civil society organisations increased after the eruption of ISIL terrorism in the Middle East (Interview GA1 2020). The interviewee (GA1) asserted that resources of the European aid programmes can be easily funeled from the Kurdish NPOs to the terror organisation itself.

Misuse of informal money transfer systems

There is evidence that both the PKK and ISIL used formal banking systems for limited numbers of activities. For instance, HDP officials transferred money to the families of arrested PKK militants via formal banking systems (Supreme Court 2021). These types of money transfers are conducted upon orders from PKK regional leaderships. Investigators observed that both organisations were extremely careful to stay below the reporting thresholds for financial transactions. Some interviewees noted that ISIL operatives in Europe wired money to Turkish banks close to the territory of Syria. The interviewee put it succinctly: Gaziantep has emerged as a significant financial centre that hosts the bank accounts of refugees, international donors and ISIL operatives who move back and forth between Turkey and ISIL territories (Interview GA2 2020). Once the jihadists arrive in border towns, they withdraw the money and cross the borders to join the ISIL camps.