Abstract

The article conducts a corpus study of official reports and papers from the Strategic Studies Institutes of the United States, NATO, the European Union, Ukraine, and Russia up to and including 2014 to determine how Russia’s hybrid war against Ukraine was represented and how postponed it proved to be. The US, EU, and NATO were very cautious and slow in establishing relations with Ukraine, either because they considered its integration with Russia very likely or because they did not want to destroy lucrative economic relations with Russia given the unstable and inconsistent foreign policy. The US, EU, and NATO were well aware of Ukraine's vulnerabilities and had been documenting various forms of Russian pressure on Ukraine since the 1990s (the preparatory phase of hybrid war) as well as the high likelihood of Russian military aggression since that time. Therefore, based on the institutes’ predictions, the Russia’s war against Ukraine was unavoidable, yet has been postponed for at least 20 years.

Keywords

‘This war for us now is undoubtedly a war for independence. We can say that this is a postponed war. Postponed for 30 years, given how we gained independence in 1991.’

Volodymyr Zelenskyy, President of Ukraine, 19 May 2022

Introduction

The existence of hybrid warfare can only be determined retrospectively, that is, after the attack phase, when the aggressor country uses military and non-military forms of pressure against the target state, but the latter forms were used during the preparatory phase (Starodubtseva 2021; Pinkas 2021). Thus, by referring to a full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 as a ‘postponed war’, the Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy (2022) accurately described the temporal essence of any hybrid war. The nonlinear nature of hybrid war manifests itself in the absence of a formal declaration of the beginning or end of hostilities, in the transition from escalation to de-escalation, and from non-military means of pressure to military and back, but some linearity can be registered retrospectively if the aggressor country's political goals are achieved, namely, regime change in the target state, seizure of territory, destruction of the target state's independence and so on (Dayspring 2015; Barber, Koch & Neuberger 2017; Sharma 2019; Qureshi 2020).

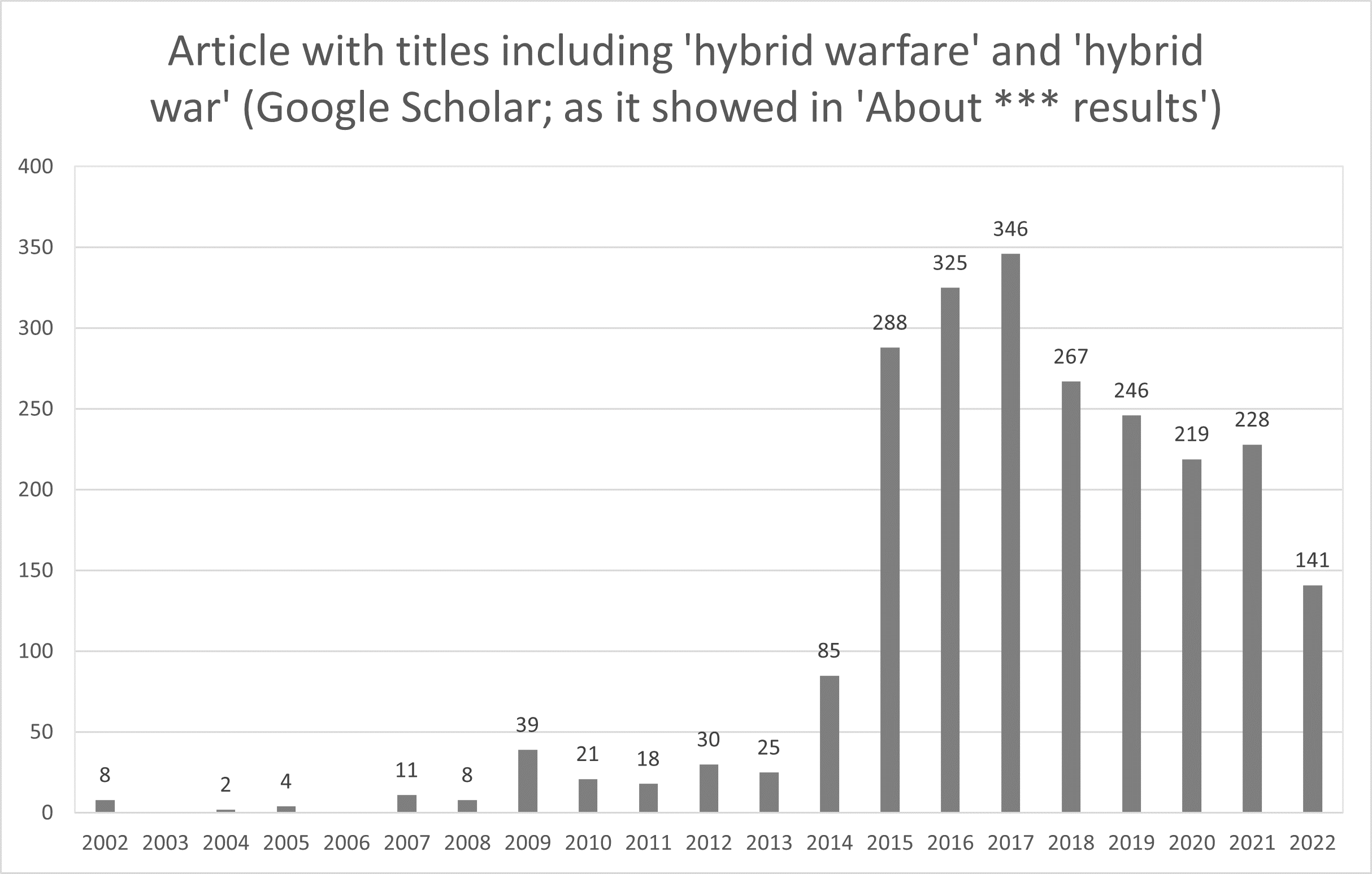

As illustrated in Figure 1, an increase in interest in hybrid warfare has only emerged since 2014, following Russia's annexation of Crimea and aggression in eastern Ukraine. In some ways, these studies were also postponed. At the same time, this can be explained by the fact that many studies have cited Ukraine's 2014 case as the most striking example of hybrid warfare in the modern world. This is not to say that there were no signs of Russia’s hybrid warfare’s preparatory phase.

Fig. 1. Article with titles including ‘hybrid warfare’ and ‘hybrid war’

Source: Figure created by authors, based on https://scholar.google.com.ua/scholar?q=allintitle%3A+hybrid+warfare&hl=ru&as_sdt=0%2C5&as_ylo=1999&as_yhi=

Here are the reasons why Russia’s hybrid war against Ukraine has been studied since 2014: to learn how to identify the first manifestations of hybrid warfare's preparatory phase, as well as how to prevent and respond to hybrid attacks on major nations, weak, failed states and countries at risk in a coordinated manner (Ioannou 2022; Abbott 2016; Murphy, Hoffman & Schaub 2016; Hayat 2021; Grimsrud 2018; Clarke 2020; Oren 2016; Vaczi 2016; Palagi 2015). According to some studies, Russia is fighting a hybrid war in Ukraine against the West, or more specifically against the liberal-democratic global status quo and Western-oriented countries in its ‘near abroad’ to protect autocratic capitalist modernisation (Filipec 2019; Demyanchuk 2019).

Furthermore, according to some studies, this war caught Ukraine, the United States, the European Union and NATO off guard in 2014, as no one expected such a coordinated, determined and military operation in Crimea and eastern Ukraine by the Russian military (Veljovski, Taneski & Dojchinovski 2017; Fridman 2018; Najžer 2022; Oğuz 2016). Is this truly the case?

We decided to investigate official reports and papers of the Russian, Ukrainian, US, EU and NATO strategic studies institutes from 1993 to 2014 in order to determine how Russia’s hybrid war against Ukraine was represented and how postponed it proved to be. These organisations research and develop security policies. As far as we know, no detailed analysis of their work has been performed. This study will help in understanding what tools of Russia's hybrid war against Ukraine were identified even before the war was conceptualised as a hybrid war.

As a result of this study, we were able to summarise the instruments of Russian hybrid warfare against Ukraine and also establish that Ukraine practically played a double game: on the one hand, claiming commitment to Euro-Atlantic integration while doing little in the way of reforms, eradicating corruption, and fearing a political and economic reaction from Russia; on the other hand, continuing to benefit from cooperation with Russia while denying the latter political and military integration and pursuing a loyal language policy that served as a springboard for the development of pro-Russian nationalism. Also, it can be stated that the United States, the European Union and NATO have been very cautious and slow in establishing relations with Ukraine, either because they believe its integration with Russia is very likely, or because they do not want to destroy profitable economic relations with Russia because of such an unstable, inconsistent partner.

This paper is organised as follows. We begin by emphasising the topic's relevance in relation to existing literature, then describe the methodological aspects, data collection and analysis process. In the following section, we present the findings and discuss them in the context of the existing literature.

Literature review

In this section, we will look at the characteristics of the preparatory phase of hybrid warfare in general, as well as in the context of Russia’s conflict with Ukraine.

On the preparatory phase of hybrid warfare

According to Nina Turkiian (2016), the preparatory phase of hybrid warfare includes the following characteristics: power is centralised and nationalist ideology spreads in the aggressor country; target country authorities are delegitimised through disinformation campaigns, bribing politicians, strengthening antagonisms in society, supporting separatist movements, and conducting trade wars.

András Rácz (2015) divides the preparatory phase into three sections: strategic, political, and operational. Strategic preparation implies, among other things, the creation of ‘loyal Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO); gaining influence in media channels in the targeted country; also influencing international audiences’ (Feher 2017: 35). Political preparation aims to delegitimise the target state’s authorities by strengthening antagonisms, bribing politicians and the military, supporting separatist movements and ‘offering profitable contracts to oligarchs and business people; establishing connection with criminal elements’ (ibid.). Operational preparation ‘launches coordinated political pressure and disinformation actions; mobilizing officials, officers and local criminal groups; mobilizing the Russian armed forces under the pretext of military exercises’ (ibid: 36). It is critical that the delegitimisation of the target state's authorities occurs not only domestically, but also in the context of international relations.

Šimon Pinkas (2021) observes, on the basis of Rácz’s research, that ‘all the mentioned activities that the attacker performs during it [preparatory phase], cannot be classified as acts of hybrid warfare on their own. They could be all considered a standard part of “diplomacy-pressure” toolbox, and on their own never exceed the imaginary threshold prompting the defending country to adopt any serious countermeasures’ (ibid: 17).

Thus, the preparatory phase of hybrid war entails a variety of measures aimed at destabilising the target country's political situation and delegitimising its authorities, enabling the use of a small contingent of irregular troops during the attack phase.

The preparatory phase of Russia’s hybrid war against Ukraine

Alina Polyakova et al. (2021) argue that ‘Russia already had experience conducting special operations in Crimea, in particular during a dispute over tiny Tuzla island in the Kerch Strait in 2003 when Russia tried to connect the Ukrainian island with its Taman Peninsula, and the campaign of Yuri Meshkov, who was elected president of Crimea in 1994 after calling for the peninsula’s accession to Russia’ (ibid: 11). At the same time, it is stated that ‘many’ such incidents occurred, ‘including “gas wars” over pricing, and Russia’s interference in Ukraine’s 2003 presidential election’ (ibid.). As a result, Russia began making territorial claims long before 2014.

Stephen Dayspring (2015) claims that ‘the 2004 election manipulation and 2006 gas war demonstrate Russia’s existing hostility toward Ukraine’ (ibid: 111). It is well known that the pro-Russian candidate Viktor Yanukovych won the 2004 presidential election with the help of Russian President Vladimir Putin and through mass falsification. It should be noted that this refers to the mid-2000s political and economic pressures.

Gage Adam (2017) points out that ‘in Ukraine, Russia . . . utilizing its own control of energy infrastructure and hydrocarbons as a weapon, and its capability to influence Ukrainian citizens through shared language and media in an attempt to convince the Ukrainian public not to trust their government’ (ibid: 7-8). The gas wars were conducted as follows: ‘Russia has used its dominance of the hydrocarbon market in order to severely damage the economy of Ukraine. This originally began in 2003 with Russia’s decision to develop alternative pipelines to bypass Ukraine, and therefore bypass Ukraine’s taxes (i.e., Blue Stream and Baltic Pipeline Systems). This was followed by an increase in gas prices to Ukraine, meant to further destabilize the economy’ (ibid: 13). Before the start of the attack phase, Russia exerted political pressure in support of pro-Russian politicians in Ukraine: ‘The events of Euromaidan in 2013-2014, which was the spark for the Ukraine crisis, can be somewhat attributed to Russian power over influential figures in Ukrainian politics. . . . Yanukovych’s decision [to suspend talks with the EU over Association Agreement] can most likely be attributed to Russian pressure and incentivizing’ (ibid: 14). Therefore, between 2003 and 2013, Russia used political and economic pressure against Ukraine.

Albina Starodubtseva (2021) lists the forms of non-military pressure in Crimea until 2014. In Crimea, a systematic organisation of a pro-Russian information and cultural field was carried out: ‘One of the largest and most influential organizations supported and financed by the Kremlin is the Russian Community of Crimea, which has been active since 1993 as an umbrella that unites 25 non-governmental organizations with 15,000 members through political, social, and economic networks. . . . These organizations have steadily served the Kremlin as a common platform for forming a Pro-Russian movement based on the Russian idea and possessing the organizational, personnel potential, and mass character to undermine confidence in the authorities and law enforcement agencies, portraying the latter as “Banderetis”’ (ibid: 35).

Russia's political pressure on Ukraine as a whole in the mid-2000s took the following forms: ‘In the political sphere, Putin relied on the formation and expansion of players affiliated with the RF in the Ukrainian institutions, namely the Party of Regions of Yanukovych and the Communist Party of Ukraine, which under the conditions of presidential-parliamentary republic blocked [Ukrainian president Victor] Yushchenko's attempts to strengthen the Euro-Atlantic course’ (ibid: 36). Economic pressure was also applied: ‘Yushchenko's rise to power [in 2004] further opened the way for oligarchs who privatized the state. Moscow supported this process in every possible way, playing on the contradictions between the oligarchs, it strengthened its economic base in Ukraine by buying up various assets’ (ibid: 37). Military pressure is also described, including military bribery, Russian spies infiltrating Ukrainian special services, and increased cooperation between Ukrainian and Russian counterintelligence agencies. In summary, Russia has systematically destabilised Ukraine's internal political situation, creating a platform for pro-Russian separatist movements.

Oleksandr Lutsenko (2021) argues that ‘most researchers believe that the Russian-Ukrainian war began in February 2014, when the military, without insignia, captured the Crimean Peninsula without firing a single shot. However, the hybrid war between Russia and Ukraine began long before the start of the real conflict. One of the components of hybrid warfare is the active manipulation of the perception of the local population and information campaigns against the enemy, which cannot be effective without a pre-identified and prepared target audience’ (ibid: 3). The author cites the establishment of pro-Russian public organisations, such as the Institute of the CIS countries, which spread Russian world ideas, as well as the use of the Russian language in the media and book publishing in Ukraine. Yurii Meshkov, who pursued a pro-Russian, separatist policy in Crimea, won the peninsula's presidential election in 1994. The following was the content of informational and cultural pressure: ‘The concept of the Russian World became the basis for the strategy of Russia's hybrid aggression against Ukraine. Historical, linguistic, political and religious narratives have become the backbone of information campaigns. The general historical experience, the expansion of the Russian Orthodox Church and the residence of a large number of Russian speakers became the basis for creating a certain reality for the target societies’ (ibid: 44). As a result, information campaigns were developed to influence, encourage and amplify linguistic and cultural differences within Ukraine.

Viacheslav Popov (2019) describes the history of the gas wars: ‘The Russian Federation did not hesitate to use Ukrainian dependence on Russian gas to put pressure on Ukraine. Russia used the “gas question” for the first time in September 1993 when, after negotiations, Ukraine exchanged part of its Black Sea Fleet ships for the cancellation of $800 million of its first gas debt to Russia. Russia understood the power of “energy weapon” and continued to use it as a lever in order to apply political and economic pressure on its opponents. In March 1994, Gazprom suspended supplies of gas to Ukraine’ (ibid: 25). It is essential that Russia used the gas issue to achieve its political goals and weaken Ukraine's independence. Gas wars were also a source of instability in the mid-2000s, and they had the potential to split the country in 2009: ‘The gas conflict of 2009 had far-reaching goals. Russia intended the absence of gas in Ukraine to play the role of a detonator in provoking East-West confrontation and political conflict in Ukraine. The idea was that in the event of a complete cessation of Russian gas supplies, the Ukrainian government would not provide gas from the Western gas storage facilities to the main industrial centers in the East, in which case those areas would remain without heat. The development of the situation was supposed to provoke, according to the plan of the Russian strategists, social protests and unrest in the eastern and southern regions of Ukraine’ (ibid: 28). Thus, Russia’s hybrid warfare against Ukraine has included economic tools since the 1990s, with significant political ramifications.

Peihao Raymond Tan (2019) devised a chronology of the hybrid war’s preparatory phase from 2000 to 2014, outlining the vulnerabilities in Ukraine that Russia exploited, namely a) the corrupt Ukrainian oligarchs, which allowed Russians to buy strategically important enterprises, b) ethnic differences and c) distrust of the authorities, which were used in supporting pro-Russian political forces in 2004, and d) the lack of a developed counterintelligence system, which resulted in the exposure of Russian spies in 2009, e) reliance on Russian gas, imports and loans (due to large national debt), as manifested in the 2006–2009 gas wars and the 2013 trade wars.

Thus, studies of Russia’s hybrid war against Ukraine reveal key elements of the preparatory phase, such as the use of non-military and paramilitary instruments to influence and destabilise the situation in Ukraine. These include direct territorial claims, support for separatist movements, the dissemination of pro-Russian informational materials, including the use of religious institutions, the bolstering of cultural and linguistic differences among populations in different regions, bribing politicians and supporting pro-Russian parties, exploiting conflicts between Ukrainian oligarchs, infiltration into Ukrainian security services and the initiation of gas wars. All of these tools were designed to counteract pro-Western, nationalistic sentiments and foreign policy in Ukraine while also fostering a stable pro-Russian sentiment in the political, cultural and informational spheres.

Using the concept of a preparatory phase of hybrid warfare and the characteristics of this phase in Russia's war against Ukraine, our article will examine official reports and papers from the US, NATO, Ukraine, Russia and the EU strategic studies institutes up to and including 2014 to determine how this hybrid war was represented and how postponed it proved to be.

We set the following objectives to achieve the goal:

1. Determine what instruments of Russian hybrid warfare against Ukraine were identified by the individual strategic studies institutes.

2. Explore what vulnerabilities made these instruments so effective from the point of view of the individual strategic studies institutes.

3. Establish the duration of the attack phase’s ‘postponement’ in the context of Russia’s hybrid war against Ukraine using findings from individual strategic studies institutes.

Materials and methods

The research material in this article consists of the works of the strategic research institutes of Russia, Ukraine, the United States, the EU and NATO from 1993 to 2014. These organisations were chosen because they are the official think tanks for security policy. The stated goals of these organisations demonstrate this. For example, the goal of the Russian Institute for Strategic Studies ‘is the information and analytical support of the federal governmental bodies when forming strategic directions of the governmental policy in the area of national security of the Russian Federation’ (Russian Institute for Strategic Studies n.d.); the National Institute for Strategic Studies of Ukraine ‘submits results of its scientific enquiry to the President of Ukraine in the form of proposals of programmatic documents, expert investigations of regulatory legal acts, analytical reports and proposals on the major grounds of domestic and foreign affairs, the ways of solution of the countrywide and provincial issues of social development’ (National Institute for Strategic Studies of Ukraine n.d.); the Strategic Studies Institute of the United States of America ‘conducts global geostrategic research and analysis that creates and advances knowledge to influence solutions for national security problems facing the Army and the nation’ (Strategic Studies Institute - US Army n.d.); the goal of the European Union Institute for Security Studies is ‘to assist the EU and its member states in the implementation of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), including the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) as well as other external action of the Union’; the Mission of the NATO Defense College is ‘to contribute to the effectiveness and cohesion of the Alliance primarily through senior-level education, on transatlantic security issues, enabled by research on matters relevant to the Alliance, and supported by engagement with Allies, Partners and Non-NATO Entities (NNEs), with a 360 degrees approach’ (NATO n.d.). As a result, it is clear that the strategic studies institutes conduct research directly related to the security of the entities in question. Investigating their works will help to understand what instruments of the hybrid war between Russia and Ukraine were noted even before the war was conceptualised as a hybrid war, as well as how delayed the attack phase of this conflict has been.

These works will need to be analysed using corpus linguistics.

Corpus linguistics is the linguistic discipline that allows ‘the complete and systematic investigation of linguistic phenomena on the basis of linguistic corpora using concordances, collocations, and frequency lists’ (Stefanowitsch 2020: 54). Corpus linguistics identifies objective linguistic characteristics of texts to empirically examine discourses that shape people’s lives in society. It analyzes the language used, including words, metaphors, to understand the formation of social subjects (Baker 2006: 92, 3-4).

It is important to define the terms that will be needed in our study. A corpus is a collection of texts selected to study the state and diversity of a language; corpus research uncovers patterns, consistent word usage and new semantic relationships. Concordance is the collection of all uses of a word form, each in its context; concordance allows for a quick understanding of a particular word's contexts, highlighting stable relationships with other words.

For our study, we will only need concordance because we will need to highlight the contexts of the use of the words ‘Russia’ and ‘Ukraine’ in the works of the strategic studies institutes in the range of 25 words to the left and right of each other. This will be accomplished with AntConc 4.1.0. Concordance analysis is a qualitative method of corpus linguistics that allows for close reading and identification of nuances in meaning. In this article, it refers to the meanings that were captured within the context of a collocation (‘Russia’ and ‘Ukraine’). Quantitative methods were not employed in this study, except for the counting and thematic categorisation of relevant concordances.

Data collection, operationalisation and analysis

For the study, five corpora were formed based on the works of the strategic studies institutes of Russia, Ukraine, the United States, the European Union and NATO, which were published between 1991 and 2014, that is, before Russia’s military actions on Ukrainian territory began. The corpora were named Corpus A, Corpus B, Corpus C, Corpus D and Corpus E, respectively. The texts for corpora from NATO, EU and US institutions were downloaded in English. The texts from the Russian Institute were downloaded in Russian and the Ukrainian corpus in Ukrainian. The necessary excerpts and concordances in the Ukrainian and English languages were translated into English by the authors of this article.

Corpus A was compiled from texts by the strategic studies institute, the US Army War College. The first part of the texts was downloaded from the Internet Archive (n.d.) after a search for ‘Russia Ukraine threat’ in TXT format, as well as in PDF format via a search on the site and an advanced Google search. A total of 30 documents published between 1993 and 2014 were used to create Corpus A (two 2014 texts were published before the events in Crimea and Donbas, so they were allowed as exceptions because the selection of texts in this range was determined after processing this Corpus); the list of sources can be found in Appendix 1. Corpus A has a word count of 702,000 without additional cleaning. The files were converted to txt and loaded into AntConc 4.1.0 without additional cleaning. Searching for the word ‘Ukrain*’ in the context of 25 words to the left and right of the word ‘Russia*’ yielded 519 concordances (asterisk means any symbol ahead). There were 77 concordances found to be relevant.

Texts from the European Union Institute for Security Studies were used to create Corpus B. Texts were downloaded in PDF format from the official website using an advanced Google search. Corpus B is comprised of 119 documents published between 1993 and 2013. Without additional cleaning, the volume of Corpus B is 5.8 million words. The files were converted to txt and loaded into AntConc 4.1.0 without additional cleaning. A search for the word ‘Ukrain*’ in the context of 25 words to the left and right of the word ‘Russia*’ yielded 1485 concordances. There were 217 concordances found to be relevant; Appendix 2 contains a list of sources.

Corpus C contains texts from the NATO Defense College as well as texts from the NATO website. The texts were obtained in PDF format from the NATO Defense College website as well as through an advanced Google search of the NATO website using the search words ‘Russia Ukraine threat’. Corpus C is comprised of 34 documents published between 1997 and 2011; Appendix 3 contains a list of sources. Without additional cleaning, the volume of Corpus C is 568,000 words. Without any additional cleaning, the files were converted to txt and loaded into AntConc 4.1.0. Concordances were generated for the first corpus (Defense College – 280 concordances) and the second (NATO website – 2129 concordances) by searching for the word ‘Ukrain*’ in the context of 25 words to the left and right of the word ‘Russia*’. There were 217 concordances found to be relevant.

Corpus D was compiled from texts by the National Institute for Strategic Studies of Ukraine (hereinafter referred to as NISS). The texts were downloaded in PDF format from the NISS website using an advanced Google search for the words ‘rossiya ukraina zagroza’ (ukr., Russia Ukraine threat). Corpus D is comprised of 74 documents published between 2006 and 2013; Appendix 4 contains a list of sources. Without additional cleaning, the volume of Case D is 2.9 million words. Without further cleaning, the files were converted to txt and loaded into AntConc 4.1.0. With a search for the word ‘Ukrain*’ in the context of 25 words to the left and right of the word ‘rossi*’, we generated 3938 concordances. There were 200 concordances found to be relevant.

A corpus E was created on the basis of works of the Russian Institute for Strategic Studies (hereinafter referred to as RISI). The works were obtained in PDF format by conducting an advanced Google search on the RISI website with the words ‘rossiya ukraina ugroza nezavisimost'’ (Russia Ukraine threat independence), (this choice of words was intended to select only texts dealing with security issues in Ukraine’s independent history). Corpus E is comprised of 20 documents published between 2007 and 2013; Appendix 5 contains a list of sources. Without additional cleaning, the volume of Corpus E was 354,000 words. Without further cleaning, the files were converted to txt and loaded into AntConc 4.1.0. Searching for the word ‘Ukrain*’ in the context of 25 words to the left and right of the word ‘rossi*/russki*’ (rus., russian) yielded 689 concordances. There are 78 relevant concordances for the study.

After generating concordances about Ukraine in the context of Russian relations from each Corpus, they were read and classified by semantic patterns. A semantic pattern is a concept that denotes the meaning of a word based on the associations of this word with other words (Velardi, Pazienza and Magrini 1989). The identification of semantic patterns aided in classifying the instruments of Russia's hybrid warfare against Ukraine, as well as in pinpointing Ukraine's vulnerabilities that allowed these instruments to be utilised. Semantic patterns were created by counting the number of similar concordances. Semantic patterns revealed the focus of the strategic studies institutes’ reports and works. This provided an opportunity to determine what aspects of Russia’s hybrid war against Ukraine were considered in reports and works from 1993 to 2014, as well as how postponed Russian military aggression turned out to be. The most important points are illustrated using quotations from the corpus.

Results

Corpus A – Strategic Studies Institute - US Army War College

Let us identify, characterise and present hierarchically the semantic patterns about Ukraine in the context of Russia that were documented based on reading and summarising the relevant concordances in Corpus A (see Table 1).

Table 1. Semantic patterns in Corpus A

|

- |

Semantic patterns |

Number of concordances |

% of the total number |

Rank |

|

1 |

Russia’s Economic and Political Pressure on Ukraine |

51 |

66,2 |

1 |

|

2 |

NATO, Europe and the United States are interested in Ukraine’s economy but have refused to guarantee its security. |

20 |

25,9 |

2 |

|

3 |

Ukrainian authorities’ inconsistency in foreign policy |

6 |

7,7 |

3 |

|

Total |

77 |

100 |

||

Source: Table created by the authors

The semantic focus of the US Strategic Studies Institute’s works, as reflected in Semantic pattern 1 with the largest number of concordances, is Russian threats to Ukraine in the form of the following instruments of hybrid warfare:

economic instruments: a ban on Ukrainian imports, gas wars (cutting off or raising gas prices due to a non-Russian-centric policy and refusal to give up nuclear weapons), and Russian capital expansion in the Ukrainian economy;

For its part, Russia does not refrain from using the economic tools of its soft-power pressure on Ukraine to keep it within its own spheres of influence. An example of such economic blackmail is the recent ban imposed on all Ukrainian imports . . . (Nalbandov 2014: 77).

political instruments: dissatisfaction with Ukraine’s European integration; drawing Ukraine closer to Russia; criticism of Yushchenko’s policies; statements about the possibility of Ukraine’s dismemberment as a result of NATO membership; direct support for the pro-Russian presidential candidate, Yanukovich (Putin’s visits to Kyiv), delegitimisation of Ukrainian statehood;

. . . positioned itself against Russia, it might cost it a threefold increase in the price of gas (an average of $4 billion per year). Putin even threatened Ukraine “with dismemberment if it persisted in trying to join the NATO alliance.” With Ukraine relying on Russia for 51.6 percent of its domestic natural gas . . . (Ghaleb 2011: 90).

military tools: scholars predicted in 1994 that Russia would seize Crimea and eastern Ukraine, using pro-Russian nationalist movements in Ukraine. At the same time, Russian officials claimed that Crimea could be returned if Crimeans so desired, as well as the possibility of holding a referendum on the subject in 1994;

. . . bad joke and the blackest treachery, the reasons for mutual suspicion grow. During 1992-93, it became clear that Russia's Parliament sought to detach Crimea from Ukraine and annex it to Russia and that a growing nationalist movement inside Crimea sought the same objective. Russia's ambassador to Ukraine stated that . . . (Blank 1994).

Russia did not recognise Ukraine's independence, instead putting pressure on it and threatening its very existence if it pursued an independent policy. Researchers attribute such Russian threats to the country's transformation into an authoritarian state, whose authorities want to reintegrate former Soviet republics into its territory, including by waging ethnic wars and supporting authoritarian regimes in those countries (Askar Akayev in the Kyrgyz Republic, Eduard Shevardnadze in Georgia). Russia aspires to be a regional leader by imposing authoritarianism on and supporting corrupt elites in the former Soviet republics, including through ethnic conflicts.

. . . than more corruption and neo-imperialism. These charges reflect Moscow's efforts to conceal its inability to defend its clients, its enormous failed intervention in Ukraine in 2004, and the misrule of the Akayev and Shevarnadze regimes. Fourth, NATO enlargement can hardly threaten Russia if one considers NATO's enormous post-1989 . . . (Blank 2007).

Semantic patterns 2 and 3 show that, despite such threats, Ukraine has pursued an inconsistent foreign policy, attempting to benefit from both Russian and Western cooperation. At the same time, having received no genuine security guarantees from the West or Russia in exchange for giving up nuclear weapons, Ukraine was vulnerable to a possible nuclear or conventional war, which Russia could easily have started.

. . . aggravates the limbo of the Ukrainian political establishment to choose a foreign policy course. As reflected in a Congressional Research Service memo, the: conflict between Ukraine's political forces has led its foreign policy to appear incoherent, as the contending forces pulled it in pro-Western or pro-Russia . . . (Nalbandov 2014: 128-129).

Due to economic necessity (payment of gas debts) and the costly process of storing weapons, Ukrainian authorities were forced to carry out the denuclearisation process. Ukraine has needed NATO since its inception as an independent country to ensure security against Russian threats, but Russia has obstructed North Atlantic integration.

Corpus B – European Union Institute for Security Studies

Let us identify, characterise and present hierarchically the semantic patterns about Ukraine in the context of Russia that were documented based on reading and summarising the relevant concordances in Corpus B (see Table 2).

Table 2. Semantic patterns in Corpus B

|

Semantic patterns |

Number of concordances |

% of the total number |

Rank |

|

|

1 |

Russia is an authoritarian country that seeks to dominate its neighbours |

93 |

42,8 |

1 |

|

2 |

Ukraine's foreign policy is inconsistent. |

59 |

27,1 |

2 |

|

3 |

Cautious European policy toward Ukraine due to the inconsistency of Ukrainian authorities and Russia's dependence/threats |

43 |

19,8 |

3 |

|

4 |

Ukraine-NATO relations are difficult due to the inconsistency of the Ukrainian authorities and Russia's dependence/threats |

22 |

10,1 |

4 |

|

Total |

217 |

100% |

- |

|

Source: Table created by the authors

The focus of the EU Strategic Studies Institute's work, as reflected in semantic pattern 1 with the largest number of concordances, is Russian threats to Ukraine in the form of the following hybrid warfare instruments:

military instruments: Russian troops were expected to deploy in Ukraine as a result of Crimean pro-Russian separatism; Yeltsin's desire to build military bases on the territories of all CIS countries, including Ukraine; it was noted that if NATO approached Russia's borders in 1994, Russian troops could be brought into Ukraine to establish military bases;

. . . and Eastern/Central Europe and advance Russian forces westward again. The pretext for any such Russian intervention would most likely be pro-Russian separatism in Ukraine, fuelled by growing political/economic centrifugal currents in the state. If Crimean separatism or economic chaos in eastern Ukraine were to result in violent . . . (Allison 1994).

economic instruments: Russian attempts to integrate the Ukrainian economy into the Russian economy; gas wars, trade wars (import bans); Russia’s capital economic expansion (purchase of oil refineries, energy infrastructure);

. . . Union, the Common Economic Space and the EurAsian Economic Community (EvrAzEs) with other post-Soviet states. At that stage bilateral economic relations between Russia and Ukraine were quite complicated. From time to time trade wars took place during which both sides imposed restrictions and quotas on each other for products . . . (Samokhvalov 2007: 14).

territorial claims: Russian authorities’ lack of political will regarding the demarcation of Ukraine’s borders with the CIS, attempted seizure of Tuzla Island; State Duma deputies’ statements about the illegality of the transfer of Crimea to Ukraine;

. . . Dniestr dispute already exists, in Russia’s highly visible meetings with the leaders of Georgia’s three separatist regions, and in Russia’s dispute with Ukraine over Tuzla island.’ Russia and the EU interpreted developments in Moldova’s conflict with its separatist region of Transnistria differently. In Moscow, there is . . . (Danilov et al. 2005: 15).

political instruments: the desire to keep Ukraine within Russia's sphere of influence, lest it becomes Russophobic and anti-Russian, as Poland has; Putin's support for pro-Russian presidential candidate Yanukovich in 2004; the politicisation of the Russian language status could result in a conflict between pro-Russian forces and the Ukrainian nationalist project, as well as political mobilisation of the Russian-speaking population;

. . . Russian CIS-expert Konstantin Zatulin: ‘If independent Ukraine lacks a special union with Russia, its independence will unavoidably be placed on an anti-Russian foundation. Ukraine may then turn into a second Poland - an alien cultural and historical project that Russia will have to learn to deal with, or else . . . (Samokhvalov 2007: 27).

Semantic patterns 2 and 3 focus on the cautious policy toward Ukraine, with a slight bias toward Russia's interests due to the EU’s economic dependence on Russia. It is noted that Ukrainian authorities' foreign policy priorities are inconsistent (e.g. Kuchma’s ‘multi-vector’ policy), seeking to balance and benefit from integration with both Euro-Atlantic and Russian institutions. Ukrainian big businesses benefited from Russian cooperation, but they soon desired independence and control over the Ukrainian economy (‘split consciousness’). For example, Russia’s military presence on Ukrainian territory (the Sevastopol Naval Base) was maintained to purchase cheap gas;

. . . an economic project, the SES had failed to capture the economic elite’s imagination. On this complex chessboard of intertwining economic and political interests, the Ukrainian oligarchs played an ambivalent game. A journalist who interviewed several big business figures characterised them as ‘split personalities’, looking East or West, speaking Russian . . . (Puglisi, Wolczuk & Wolowski 2008: 79).

Semantic pattern 4 highlights the ‘schizophrenic’ nature of Ukrainian capital, revealing the true Ukrainian subjectivity that has served as a genuine impediment to Euro-Atlantic integration and a deterrent to integration with Russia. Ukrainians are unwilling to pay for real independence because the economic costs of breaking away from Russia are severe.

Corpus C – NATO Defense College

Let us identify, characterise and present hierarchically the semantic patterns about Ukraine in the context of Russia that were documented based on reading and summarising the relevant concordances in Corpus C (see Table 3).

Table 3. Semantic patterns in Corpus C

|

Semantic patterns |

Number of concordances |

% of the total number |

Rank |

|

|

1 |

Russia opposes Ukraine’s accession to NATO |

71 |

29,8 |

1 |

|

2 |

Russia’s policy of undermining Ukraine's sovereignty. Russian instruments of pressure on Ukraine |

66 |

27,7 |

2 |

|

3 |

Ukraine’s foreign policy aims to strike a balance between the East and the West |

49 |

20,5 |

3 |

|

4 |

Ukraine's Issues as an Independent State |

34 |

14,2 |

4 |

|

5 |

Western perceptions of Ukraine |

18 |

7,5 |

5 |

|

Total |

238 |

100% |

- |

|

Source: Table created by the authors

The focus of the work of the NATO Strategic Studies Institute, as reflected in Semantic pattern 1 with the highest number of concordances, is the relationship with Ukraine:

cautious so as not to provoke Russia,

cold as a result of Ukraine’s inconsistent foreign policy,

interested, as Ukraine will be able to ensure its security, protect itself from potential Russian aggression and serve as a model of democratisation for Russia, effectively suspending its function as an expansionist state. Due to its ethnic proximity to Russia, Ukraine cannot maintain a neutral position.

At the same time, NATO believed that, while Russia opposed Ukraine’s accession to the EU and questioned Ukrainian statehood, it would not resort to military aggression, but could raise the Crimea issue. Furthermore, there was no public support in Ukraine for accession to NATO.

The statements about Russian threats to Ukraine in the form of the following instruments of hybrid warfare occupy an important place in this corpus:

ideological instruments: non-recognition of Ukrainian statehood (as evidenced not only by authorities, but also by polls of the Russian population); the dominance of Russian sources of information in the Ukrainian information sphere, the spread of the ideology of ‘ethnic brotherhood’, stereotypes about NATO, and so on, while any support for the Ukrainian language and culture is viewed as a threat to Russia. Any independent, non-Russian-centric Ukrainian policy is thought to be influenced by the West;

. . . stereotypes concerning NATO, Ukraine and Russia to the best for the Russian leaders’ advantage. The not less important direction of Russian predominance policy is engaging Ukraine to the Byelorussian-Russian Union on the basis of so-called ‘brotherhoods of the Slavic peoples’. The significant external problem of integration of Ukraine . . . (Perepelitsya 2001).

political instruments: the democratic transformation in Ukraine (‘Orange Revolution’) is viewed by the West as a plot against Russia; the Russian authorities want to regain control of Ukraine’s internal and foreign policy, reintegrate it into a union with Russia and end Ukraine’s existence as an independent state. If Ukraine joins NATO, the Russian-speaking population in Crimea is likely to mobilise politically. The politicisation of the Russian language issue – criticism of alleged discrimination against the Russian-speaking population;

. . . considerable period of time; it was not initiated by the Orange leadership after 2005. Russia is still a very important factor in nearly all aspects of Ukraine's foreign and security policy. Moscow is firmly convinced that the entire cooperation between Ukraine and NATO is nothing but directed against Russia (NATO Library 2010: 7).

territorial claims: Russia did not demarcate the borders between the states; the conflict over Tuzla Island; the mayor of Moscow referred to Sevastopol as a ‘Russian city’ in 1997; the Russian-speaking elite and Russian nationalists in Crimea could be mobilised for annexation, which was considered quite possible;

. . . Sevastopol, Black Sea Fleet, Russian minority and Russian language in Ukraine, informational war, ‘Gazprom’’s expansion attempts. I would just like mention that in May 1994 Ukraine and Russia were very close to the edge at which the war could start. Then, at the expense of unimaginable attempts, it became possible . . . (Zhovnirenko 1997: 35).

economic instruments: the expansion of Russian business in Ukraine at the beginning of the twenty-first century (oil refining, defence industry); increasing reliance on gas – preventing Ukraine from diversifying its energy supplies;

. . . has always been fraught with complex foreign policy problems. From 2000 to 2004, Russia sought control of key sectors of the Ukrainian economy, thereby aiming to ensure Ukraine’s political dependence on Russia. In this period, Ukrainian-Russian relations witnessed a considerable advance of the Russian Federation in terms of the realization . . . (Kozlovska 2006: 53).

military instruments: in May 1994, Crimea held a referendum on greater autonomy and dual citizenship (Russian and Ukrainian), but the Ukrainian authorities did not recognise it, raising the possibility of civil war or war with Russia; the presence of the Black Sea Fleet in Crimea poses a threat; and the possibility of Ukraine annexing Crimea and turning its territory into a military base;

In 1993-1994, with its economy in tatters, separatist movements on the rise, and relations with the Russian Federation in a downward spiral, the potential for a Ukrainian civil war, or external conflict with Russia, was widely assessed as acute. Today, the threat of overt hostilities seems to be minimal. Ukraine has . . . (Nation 2000: 8).

The researchers believe that these threats are related to Russia's failure to democratise. At the same time, it is noteworthy that the West’s interests in supporting Ukraine are named: it will allow Russia to restrain its expansionism, but with Ukraine's obsessive mobilisation against Russia, a conflict may arise. At the same time, the West was reluctant to integrate Ukraine due to the country’s inconsistent foreign policy and the risk of deteriorating relations with Russia. Ukraine’s foreign policy is influenced by the country's large Russian-speaking population (threat of ethnic mobilisation by Russia) and reliance on Russian gas (trade wars).

They emphasise the real difficulties and problems of Ukraine’s formation as an independent state (Russification, lack of statehood experience, economic crises, pro-Russian views of the population, Russian pressure, separatist movements), but, in contrast to Russia’s delegitimising rhetoric, they see prospects for a more democratic, free society in Ukraine, looking forward, whereas Russians ‘want to return to the past’.

. . . during the winter of 2005-2006. However, these attempts have not proved to be very effective. Unlike the Russians, tempted by a return to the past, the Ukrainians clearly want to leave the Soviet era behind them, no matter what price they have to pay. The political environment is uncertain, marked by . . . (NATO Library 2010: 19).

Russia’s expansion and criticism of Ukrainian statehood provoked a pro-Western, nationalist attitude in Ukraine.

Corpus D – National Institute for Strategic Studies of Ukraine

Let us identify, characterise and present hierarchically the semantic patterns about Ukraine in the context of Russia that were documented based on reading and summarising the relevant concordances in Corpus D (see Table 4).

Table 4. Semantic patterns in Corpus D

|

Semantic patterns |

Number of concordances |

% of the total number |

Rank |

|

|

1 |

Russian Meddling in Ukraine’s Political, Economic and Cultural Space |

104 |

52 |

1 |

|

2 |

The causes of Ukraine’s vulnerabilities |

96 |

48 |

2 |

|

Total |

200 |

100% |

- |

|

Source: Table created by the authors

The focus of the works of the National Institute for Strategic Studies of Ukraine, as reflected in Semantic pattern 1 with the largest number of concordances, is Russian threats to Ukraine in the form of the following instruments of hybrid warfare:

information instruments: Russian cultural product dominance in Ukraine with an authoritarian, imperial ideology, distribution of Russian ideology (imperial, Soviet mythology), Russification of the language and cultural space, and betterment of Russia's image on Ukrainian territory;

In the cultural field - in the strengthening of the competition of the Ukrainian cultural product with the Russian one. Today, the cultural product of Russian origin dominates the Ukrainian market, which harms the economic interests of Ukraine. The growth of its volumes is a reflection of foreign control over highly profitable sectors of the economy - the media market, film production and distribution, book publishing, etc. The weakness of state policy in the cultural sphere, . . . (Gritsak 2006: 24; translation from Ukrainian hereinafter is ours – I.V., O. N.).

political instruments: pro-Russian organisations politicise the Russian language issue, contributing to Ukraine’s division into ‘West’ and ‘East’; Russian influence expands into all spheres of activity, ‘if not to the point of annexing Ukraine, then to disregard its Ukrainianness’ (see below); according to a 2013 study, Russia will use economic pressure, pro-Russian social movements aimed at the integration of Ukraine with Russia, and spread the idea of discrimination of Russian-speaking minority rights;

. . . is focused on eroding support for the European Neighborhood Policy and introducing Russian as the second official language. Another goal is to expand its influence in all spheres of Ukraine's activity, and if not annex it, then at least to negate its Ukrainianness. As a result of the inequality of economic and military power between Kyiv and Moscow . . . (Zhalilo and Yanishevsʹkyy 2011: 161).

economic instruments: Russian business expansion, particularly in the energy sector; gas and trade wars; Russia is critical of Ukraine's European integration because it is viewed as a threat to the country; presentation of plans for Ukraine’s reintegration into the Russian alliance; integration into the Customs Union entails full acceptance of Russian geoeconomic influence, limiting Ukraine’s economic sovereignty; Russian banks are acquiring strategically important Ukrainian assets;

. . . Russian investments in Ukraine and related risks. The Russian capital has intensified its expansion into post-Soviet countries in the past decade, and Ukraine is one of the priority areas for Russian capital. The latter effectively integrates the objects acquired in Ukraine into its transnational companies or uses them to recreate closed . . . (Zhalilo 2011: 46).

ideological tools: reverence of all things Russian and denigration of all things Ukrainian, delegitimisation of Ukrainian statehood and people (‘under-nation’, artificial, constructed) in science, politics and popular consciousness; ‘Good Ukraine’ is subservient Little Russia (‘Malorossia’), and ‘bad Ukraine’ is named after famous Ukrainian national heroes (‘Banderovskaya’, ‘Petlyurovskaya’ and ‘Mazepovskaya’). Russians refuse to acknowledge the Holodomor and are unwilling to talk about the mass de-ethnicisation of Ukrainians in Russian history (prohibition of Ukrainian writing in the Russian Empire). Ukrainians are considered Russians by Russians because they both originated in Kyivan Rus.

. . . Russians who are ‘Easterners’ have a negative stereotype of Ukrainians who are ‘Westerners’ and vice versa. ‘Mazepan,’ ‘Petliurist,’ ‘Makhnovist,’ and ‘Banderite’ appear in the perception of the average Russian on a subconscious level as a kind of ‘anti-ideal’ of Ukraine, as a living embodiment of ‘bad Ukraine’ in contrast to the ideal of good Ukraine, Malorossia, which is under the full political and spiritual control of Moscow. Characteristic ideas about . . . (Stepyko 2011: 270).

territorial claims: the border between the countries is not delimited; the conflict over Tuzla Island;

. . . the need to delimit the Kerch Strait as a border and recognize the inter-republican border between the Ukrainian SSR and the RSFSR as the state border between Ukraine and the Russian Federation. Implementation of this option would allow Ukraine to preserve the Kerch–Yenikale canal. In fact, the Kerch delimitation impasse blocks the entire process of resolving the issue of Ukrainian-Russian maritime borders both in terms of determining the endpoints in the adjacent Azov and . . . (Yermolayev 2010a: 431).

Considerable attention is given to the history of assimilation, Russification and suppression of the Ukrainian people under the rule of the Russian Empire, and the Soviet Union, which created linguistic, cultural and regional distortions in Ukraine (an industrialised but Russian-speaking southeast, but a nationalised west), which are precisely politicised by pro-Russian forces to reintegrate Ukraine into a union with Russia. Meanwhile, Ukrainian scholars highlight the lack of language policy (the protection of the Ukrainian language in Ukraine), as well as the inconsistency of foreign policy (European integration in words, but in practice the preservation of authoritarian, corrupt tendencies).

The European integration policy was not supported by practical actions. The Eastern policy was, in fact, fragmented and poorly calculated. The trust with Ukraine's strategic partner, the Russian Federation, was completely lost. Destroyed ties, trade wars, and unfavorable gas agreements in 2009 are the logical consequence of this foreign policy. With the sham foreign policy activity of almost . . . (Yermolayev 2010b: 40).

However, this inconsistency can be explained by an attempt to exploit the contradictions between the West and Russia, taking advantage of ‘simultaneous movement in different directions,’ which can be seen in both politics and opinion polls. Simultaneously, the need to continue balancing is asserted. According to a 2013 study, the competition between Russia and the EU for influence over Ukraine's economic integration processes has intensified.

Corpus E – Russian Institute for Strategic Studies

Let us identify, characterise and present hierarchically the semantic patterns about Ukraine in the context of Russia that were documented based on reading and summarising the relevant concordances in Corpus E (see Table 5).

Table 5. Semantic patterns in Corpus E

|

Нет |

Semantic patterns |

Number of concordances |

% of the total number |

Rank |

|

1 |

Ukraine’s inconsistent policy towards integration with Russia |

29 |

37.1 |

1 |

|

2 |

Russia and Ukraine's mutual ‘demonization’ |

18 |

23 |

2 |

|

3 |

Projects for Ukraine’s integration into the Union State with Russia |

14 |

17,9 |

4 |

|

4 |

Attitudes toward Ukrainian presidents |

15 |

19,2 |

3 |

|

5 |

Threats from Russia |

2 |

2,5 |

5 |

|

Total |

78 |

100% |

- |

|

Source: Table created by the authors

The focus of RISI’s work is the investigation of the problem of integrating Russia and Ukraine into a single Eurasian state for joint economic, political and cultural development. Ukraine's lack of integration with Russia stems from Kyiv’s unwillingness to cede control of the domestic economy and politics. Ukrainian business owners are concerned about Russian economic expansion and takeovers of strategic enterprises.

. . . capital does not want any stable and long-term economic alliances with Russia, which can turn into a deep integration of the economies of the two countries and limit its independence. In addition, Ukrainian FIGs (which are at the same time sponsors of the Party of Regions, such as the Akhmetov and Firtash ‘groups’) consider the relevant sectors of the Russian economy as their strongest competitors, especially . . . (Guzenkova et al. 2011: 103; translation from Russian hereinafter is ours – I.V., O. N.).

It is emphasised that Ukrainian capital is interested in cheap Russian gas, and Russia has been providing gas to Ukrainian capitalists at low prices in the hope of greater economic integration. The country juggles between Russia and the European Union, manufacturing goods with cheap gas and selling them to the EU. According to Russian sources, this explains Ukraine’s inconsistency in foreign policy.

The only way for Ukraine to be able to make the transition is by restoring economic ties with Russia and other post-Soviet countries. It is increasingly difficult for Ukraine to manoeuvre between Russia and the European Union. Previously, the Ukrainian government was able to manoeuvre geopolitically due to its relative economic independence and its remaining industrial potential. But as it has been lost and its debt dependence on the IMF grows, it is becoming more and more difficult to do so. . . (Guzenkova et al. 2011: 92).

However, as economic self-sufficiency and industrial potential are lost, it is becoming more difficult to do so. Already near the end of President Leonid Kuchma's first term, the Ukrainian government began to exert pressure on Russian firms, limiting their future development; this trend accelerated in 2002-2004.

At the same time, scholars completely delegitimise Ukrainian statehood and national idea in the Semantic pattern 2: Ukraine ‘has failed as a state’; democracy in Ukraine is ‘phoney’; Ukraine is an economically weak country within the sphere of US and EU interests; and the Ukrainian Russophobe project is supported by the West.

The fact that Ukraine and Russia interact very sluggishly, even though Ukrainians have strong sympathies for the Russians. Of course, Ukraine's greatest pain is that it has failed as a state. After all, the state is not only official institutions and officials; it is primarily a question of the attitude of the people . . . (Guzenkova et al. 2011: 83).

Much dissatisfaction has been expressed over the denial of Soviet-Russian history in Ukraine, a ‘rewriting’ of history in which Russia's role is demonised: the country is considered a coloniser, imposing its system and way of life on the neighbouring country, and Ukraine is a colony; individuals and organisations (OUN-UPA) divorced from shared history with Russia are heroised.

. . . Ukraine is different. In his time, the national classic V. Korolenko argued that Ukrainian nationalism is the most sham. And it is no coincidence that Ukraine has now elevated the rewriting of history to the rank of the main task of the country. Of course, on the grounds of falsifying history and contrasting everything Ukrainian with Russian, the government not only ideologically substantiated the Ukrainian identity, but also . . . (Pakhomov 2009: 69).

Semantic Pattern 3 emphasises the importance of integrating Ukraine and Russia into ‘United Eurasia’, ‘Holy Russia’ and ‘interstate modernization alliances’, arguing that the Ukrainian economy will not function normally under conditions of European integration, which promises only degradation, deindustrialisation and the extinction of the village.

. . . spiritual and civilizational potential in the interests and with the help of the states that geographically form the basis of Holy Russia. Holy Russia existed not in the borders of the present Russian Federation, Ukraine or Belarus, but included and includes all territories simultaneously. Holy Russia is the aspiration of a single people to holiness and quite strict moral and ethical norms of life . . . (Guzenkova et al. 2011: 87).

Another preference for big national capital is a free trade zone with the EU for Ukraine, which will allow them to continue enriching themselves at the expense of other sectors of the economy. At the same time, it is emphasised that the majority of Ukrainians, as well as small and medium-sized businesses, support unification with Russia, which the Ukrainian leadership completely ignores. The term ‘Holy Russia’ refers to the union of Ukraine, Russia and Belarus, as well as the desire of one people for holiness and quite strict moral and ethical standards of life.

Semantic pattern 4 provides opposed assessments of presidents Viktor Yushchenko and Viktor Yanukovich: while the former is a pro-Western, Russophobe politician leading Ukraine to economic destabilisation and fearing ‘the threat of military invasion by Russia’ (in 2010!), the latter is a pro-Russian politician balancing the West and Russia, but at the same time as not being entirely loyal to Russia (not fulfilling the Kremlin’s wishes regarding ensuring the rights of Russian-speaking citizens, not granting Russian capital access to the Ukrainian market, not offering more attractive conditions for the Black Sea Fleet), but who closed the Yushchenko Institute for National Security because it was frightened of the ‘threat of invasion by Russia.’

The Ukrainian and international public was persistently frightened by the ‘threat of a military invasion by Russia’ and repeatedly voiced the idea that ‘a provocation by Russia on Ukrainian territory and the use of military force could take place at any moment...’. But the problem is that one of the main actors and apologists of the ‘Orange Maidan’ ideology . . . (Moro 2010: 74).

Russians expected more from Yanukovych, including the protection of Russian-speaking citizens' rights, nuclear cooperation and greater access to the Ukrainian market for Russian capital.

Semantic Pattern 5 estimates that if Ukraine moves westward, Russia will take measures to protect its economic and political interests, as well as the emergence of conflicts in Ukraine between the country’s east and west.

Discussions on major regional projects, such as building a bridge across the Kerch Strait or modernizing Ukraine's port infrastructure, should be intensified. It cannot be ruled out that Ukraine's further movement toward the West will require Russia to take active measures to protect its own economic and political interests . . . (Guzenkova et al. 2011: 94).

Thus, how does the RISI's work reflect the preparatory phase of the Russian-Ukrainian hybrid war? There were no direct statements about the likelihood of such an event. Furthermore, the researchers dismiss this possibility, citing Yushchenko's remarks about the threat of a Russian attack. However, the tone of Russian scholars' positions is passive-aggressive: Ukraine has failed as a state; without Russia, it cannot ensure economic stability. Simultaneously, options for political and economic integration with Russia are presented as necessary and the only correct choice of Ukrainian authorities, that is, Ukraine can exist only in an alliance with Russia. It is predicted that Russia will intervene, resulting in a conflict between the West and the East in Ukraine. It is worth noting that the researchers relied on surveys of Ukrainians, which revealed a favourable attitude toward Russians and the prospect of integration with Russia. This public opinion preparedness in the southeast of Ukraine was crucial in the context of the annexation of Crimea and parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions in 2014.

Conclusion

We were able to summarise the instruments of Russian hybrid warfare against Ukraine by conducting a corpus study of official reports from strategic studies institutes in the United States, NATO, Ukraine and the European Union published from 1993 to 2014. These organisations described economic, political, informational, territorial, ideological and military instruments of Russian pressure on Ukraine, while Russia in various forms refused to recognise Ukraine as an independent country and the Ukrainian people as distinct from the Russian people. Russia also attempted to subjugate Ukraine by mobilising the ethno-territorial Russian-speaking minority to support pro-Russian separatists.

Thus, the corpora of the US, EU, NATO, Russian and Ukrainian strategic studies institutes demonstrate the importance of ethno-territorial nationalism in Russian politics, ideology and rhetoric. This is the basis for annexing the territories of ‘near abroad’ countries through a hybrid war: delegitimising the authorities, emphasising historical, cultural and linguistic proximity of peoples (de-ethnicisation), making accusations of discrimination against the ethnic and territorial Russian-speaking minority, implementing economic, informational and political pressure, and mobilising pro-Russian nationalists.

The United States and NATO predicted a war between Russia and Ukraine in the context of the Crimean referendum and pro-Russian nationalist sentiment on the peninsula in 1994 (as was stated in the publications of relevant strategic studies institutes). In this regard, the attack phase of Russia's hybrid war against Ukraine has been postponed for at least 20 years – until 2014. However, the literature on Russia's hybrid warfare against Ukraine cites another date, the gas wars of 2006–2009, as possibly initiating the attack phase in addition to 1994.

As a result, it can be argued that the preparatory phase of Russia's hybrid war against Ukraine began in 1991, with the use of various pressure instruments, as well as the beneficial cooperation of Ukrainian and Russian capital due to interdependencies related to gas supply and transit, import-export of raw materials and products, which was conditioned, in particular, by the existence of a single industrial complex under the Soviet economy.

Because Ukraine's foreign and domestic policy has been inconsistent and ‘balanced’ since 1991, this preparatory phase of the war did not lead to an attack phase. Ukraine’s economic dependence on Russia has resulted in a fundamental inconsistency in its foreign policy trajectory, with the country constantly oscillating between Euro-Atlantic and pro-Russian integration paths. The inconsistency of the foreign policy of the Ukrainian ruling class and the political elite is evidenced by studies conducted by strategic studies institutes in the United States, the European Union, NATO, Russia and, to a lesser extent, Ukraine.

In this context, the findings of the strategic studies institutes prior to and including 2014 are quite consistent with the findings of recent studies of Russian hybrid warfare against Ukraine.

Ukrainian capital was defending itself against Russian capital encroachment, seeking security guarantees and preferential treatment from western capitalism while maintaining a profitable relationship with Russia. This is the true subjectivity of the Ukrainian elite. As a result, the West has never had ‘external control’ over Ukraine’s foreign policy, as Russia claims.

Ukraine practically played a double game: on the one hand, claiming commitment to Euro-Atlantic integration while doing little in the way of reforms, eradicating corruption, and fearing a political and economic reaction from Russia; on the other hand, continuing to benefit from cooperation with Russia while denying the latter political and military integration and pursuing a loyal language policy that served as a springboard for the development of pro-Russian nationalism. These adaptation tactics were successful until Russian soldiers set foot on Ukrainian territory, forcing a reorientation in one direction, albeit to the last, until 24 February 2022, when every opportunity for profitable economic relations with the aggressor country was exploited. One of the highlights of the work of the US, EU, NATO, Russian and Ukrainian strategic studies institutes is a focus on Ukraine’s vulnerabilities. However, the main characteristics of this inconsistency, the duality of Ukrainian elites, have been noted in the hybrid warfare literature.

It can be stated that the United States, the European Union and NATO have been very cautious and slow in establishing relations with Ukraine, either because they believe its integration with Russia is very likely, or because they do not want to destroy profitable economic relations with Russia because of such an unstable, inconsistent partner.

The analysis of pre-2014 publications from the strategic studies institutes of the United States, NATO, the European Union, Russia and Ukraine in the context of the postponed nature of Russia’s hybrid war against Ukraine reveals that all the mentioned actors were fully aware of the high likelihood of conflict escalation. They identified various forms of pressure exerted by Russia on Ukraine, yet failed to take any preventive measures. Understanding that state and supranational actors acknowledge the probability of a hot phase of hybrid warfare enables more effective action, aiming to avert dire consequences for humanity in other current or future instances of hybrid warfare. The significance of this study lies not only in providing insights but also in enabling civil society to utilise open access to the publications from the strategic studies institutes to influence authorities and advocate for non-military resolutions of conflict situations between countries. Furthermore, the open access to these publications helps avoid the formation of conspiratorial theories regarding geopolitics and fosters a comprehensive understanding of the complexities of international relations, without demonising certain actors at the expense of deification of others. This study demonstrates that the inability to act based on current research is a significant challenge within contemporary international relations.

***

Illia Ilin is an Associate Professor at the Department of Theoretical and Practical Philosophy named after Prof. J. B. Schad, V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University, Ukraine. His main research focus is the philosophical problem of reading (Althusser, Marx, Latour) and the elaboration of the corpus approach to reading.

Olena Nihmatova has a PhD in Economics, and is currently an independent scholar. She is actively adapting corpus linguistics for marketing studies. Previously, she worked at Lugansk National Agrarian University (Ukraine) and defended her thesis about the development of the organic market in Ukraine.

References

Abbott, K. (2016): Understanding and Countering Hybrid Warfare: Next Steps for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (Major research paper). Ottawa: University of Ottawa, <accessed online: https://ruor.uottawa.ca/bitstream/10393/34813/1/ABBOTT%2c%20Kathleen%2020161.pdf>.

Adam, G. (2017): Evaluating the Success of Russian Hybrid Warfare in Ukraine (Honors thesis). Mississippi: The University of Mississippi, <accessed online: https https://egrove.olemiss.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1344&context=hon_thesis>.

Allison, R. (1994): Peacekeeping in the Soviet Successor States. Paris: Institute for Security Studies of WEU.

Baker, P. (2006): Using Corpora in Discourse Analysis. London: Continuum.

Barber, V., Koch, A. & Neuberger, K. (2017): Russian Hybrid Warfare. Medford: Fletcher School, Tufts Univ.

Blank, S. J. (1994): Proliferation and Nonproliferation in Ukraine: Implications for European and US security. Final report (No. AD-A-283937/1/XAB). Carlisle Barracks: Strategic Studies Inst., <accessed online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep11595>.

Blank, S. J. (2007): From Munich to Munich. Strategic Studies Institute. U.S. Army War College, 1 April, <accessed online: https://press.armywarcollege.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1253&context=articles_editorials>.

Clarke, M. (2020): Russian Hybrid Warfare. Washington, D.C.: Institute for the Study of War.

Danilov, D., Karaganov, S., Lynch, D., Pushkov, A., Trenin, D. & Zagorski, A. (2005): What Russia Sees. European Union Institute for Security Studies, January, <accessed online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/430da90f-577c-430e-84b1-4913014c2388>.

Dayspring, S. M. (2015): Toward a Theory of Hybrid Warfare: The Russian Conduct of War During Peace (Master’s thesis). Monterey: Naval Postgraduate School, <accessed online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA632188.pdf>.

Demyanchuk, T. (2019): Understanding of Hybrid Warfare in Ukraine: To What Extent This Understanding is Shaped by Its Internal Experience? (Master’s thesis). Prague: Charles University, <accessed online: https://dspace.cuni.cz/bitstream/handle/20.500.11956/109965/120343109.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y>.

Feher, A. (2017): Hungary’s Alternative to Counter Hybrid Warfare-Small States Weaponized Citizenry (Master’s thesis). Fort Leavenworth: US Army Command and General Staff College, <accessed online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1038681.pdf>.

Filipec, O. (2019): Hybrid Warfare: Between Realism, Liberalism and Constructivism. Central European Journal of Politics, 5(2), 52-70.

Fridman, O. (2018): Russian ‘Hybrid Warfare’: Resurgence and Politicization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ghaleb, A. (2011): Natural Gas as an Instrument of Russian State Power. Carlisle: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College.

Grimsrud, K. R. (2018): Moving into the Future: Allied Mobility in a Modern Hybrid Warfare Operational Environment (Master’s thesis). Fort Leavenworth: US Army Command and General Staff College, School for Advanced Military Studies, <accessed online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1071085.pdf>.

Gritsak, Y. I. (2006): Ukrayina v 2006 Rotsi: Vnutrishnye i Zovnishnye Stanovyshche ta Perspektyvy (2006) [Ukraine in 2006: Internal and External Situation and Prospects]. Kyiv: National Institute for Strategic Studies.

Guzenkova, T. et al. (2011): Rossiya-Ukraina: Shagi k Modernizatsionnomu Al'yansu?, [Russia-Ukraine: Steps towards a Modernization Alliance?] (2011). Problemy natsional'noy strategii, 4(9), 77-106.

Hayat, R. (2021): Hybrid Warfare: A Challenge to National Security. PCL Student Journal of Law, 5(1), 102-127.

Ioannou, K. (2022): Hybrid Warfare: Theory, Case Studies and Countermeasures (Master’s thesis). Piraeus: University of Piraeus, <accessed online: https://dione.lib.unipi.gr/xmlui/bitstream/handle/unipi/14913/Kyriakos%20I.%20Ioannou_AM%20%CE%9C%CE%9821019_MA%20Thesis_Hybrid%20Warfare%20Theory%2C%20Case%20studies%20and%20Countermeasures_PMS%20DES_2021_2022.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y>.

Kozlovska, O. (2006): Roadmap for Ukraine’s Integration into Transatlantic Structures. Rome: NATO Defense College.

Lutsenko, O. (2021): Russian Hybrid Warfare in Ukraine: The Annexation of Crimea and the Donbas War (Master’s thesis). Prague: Charles University, <accessed online: https://dspace.cuni.cz/bitstream/handle/20.500.11956/127322/120387372.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y>.

Moro, G. I. (2010): Prezidentskiye Vybory na Ukraine: Realii i Perspektivy Razvitiya Rossiysko-Ukrainskikh Otnosheniy [Presidential Elections in Ukraine: Realities and Prospects for the Development of Russian-Ukrainian Relations]. Problemy natsional'noy strategii, (2), 69-79.

Murphy, M., Hoffman, F. G. & Schaub, G. (2016): Hybrid Maritime Warfare and the Baltic Sea Region. Copenhagen: Centre for Military Studies. University of Copenhagen.

Najžer, B. (2020): The Hybrid Age: International Security in the Era of Hybrid Warfare. London: I. B. Tauris.

Nalbandov, R. (2014): Democratization and Instability in Ukraine, Georgia, and Belarus. Carlisle Barracks: The United States Army War College.

Nation, R. C. (2000): NATO’s Relations with Russia and Ukraine. NATO: Office of Information and Press, June, <accessed online: https://www.nato.int/acad/fellow/98-00/nation.pdf>

National Institute for Strategic Studies of Ukraine (n.d.): General Information. National Institute for Strategic Studies, <accessed online https://niss.gov.ua/en/general-information>.

NATO Defense College (n.d.). NATO Defense College Mission. NATO Defense College, <accessed online: https://www.ndc.nato.int/about/organization.php?icode=23>.

NATO Library (2010): Ukraine After the Orange Revolution (Backgrounder, t. 1). NATO Library, 9 February, <accessed online: https://www.nato.int/structur/library/bibref/back0110.pdf>.

Oğuz, Ş. (2016): The New NATO: Prepared for Russian Hybrid Warfare? Insight Turkey, 18(4), 165-180.

Oren, E. (2016): A Dilemma of Principles: The Challenges of Hybrid Warfare from a NATO Perspective. Special Operations Journal, 2(1), 58-69.

Pakhomov, Y. N. (2009): Ukraina i Rossiya: Effekty Vzaimodopolnyayemosti i Riski Ottorzheniya [Ukraine and Russia: Complementarity Effects and Rejection Risks]. Problemy natsional'noy strategii, 1, 62-77.

Palagi, J. E. (2015): Wrestling the Bear: The Rise of Russian Hybrid Warfare (Master’s thesis). Norfolk: National Defense University, VA Joint Forces Staff College, <accessed online: https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=814892>.

Perepelitsya, G. (2001): The Final Report of Project ‘A Distinctive Partnership Between North Atlantic Treaty Organisation and Ukraine as a New Type of Relations in the Euro-Atlantic Security Architecture’. NATO Institute for Security Studies, <accessed online: https://www.nato.int/acad/fellow/99-01/perepelytsya.pdf>.

Pinkas, Š. (2021): The American Hybrid War? Operation Enduring Freedom through the Hybrid Warfare Lenses (Master’s thesis). Prague: Charles University, <accessed online: https://dspace.cuni.cz/bitstream/handle/20.500.11956/127609/120387214.pdf?sequence=1>.

Polyakova, A. et al. (2021): The Evolution of Russian Hybrid Warfare. CEPA, 28 March, <accessed online: https://cepa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/CEPA-Hybrid-Warfare-1.28.21.pdf>.

Popov, V. (2019): Robust Civil-Military Relations – One of the Most Powerful Tools to Counteract Russian Hybrid Warfare: The Case of Ukraine (Master’s thesis). Monterey: Naval Postgraduate School, <accessed online: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/92/ROBUST_CIVIL-MILITARY_RELATIONS%E2%80%94ONE_OF_THE_MOST_POWERFUL_TOOLS_TO_COUNTERACT_RUSSIAN_HYBRID_WARFARE-_THE_CASE_OF_UKRAINE_%28IA_robustcivilmilit1094562284%29.pdf>.

Puglisi, R., Wolczuk, K. & Wolowski, P. (2008): Ukraine: Quo Vadis? Paris: Institute for Security Studies.

Qureshi, W. A. (2020): The Rise of Hybrid Warfare. Notre Dame Journal of International and Comparative Law, 10(2), 173–208.

Rácz, A. (2015): Russia's Hybrid War in Ukraine: Breaking the Enemy's Ability to Resist. Helsinki: Finnish Institute of International Affairs.

Russian Institute for Strategic Studies (n. d.): Ob institute [About the institute]. RISI, <accessed online: https://riss.ru/en/ob-institute/tseli-i-zadachi>.

Samokhvalov, V. (2007): Relations in the Russia-Ukraine-EU Triangle: 'Zero-Sum Game' or Not? European Union Institute for Security Studies, September, <accessed online: https://www.academia.edu/1356312/Relations_in_the_Russia_Ukraine_EU_Triangle_zero_sum_GameOr_Not>.

Sharma, R. (2019): Contextual Evolution of Hybrid Warfare and the Complexities. CLAWS Journal, 12(2), 1-14.

Starodubtseva, A. (2021): Russian Hybrid Warfare in Ukraine: Comparative Analysis of Two Cases and Identification of Critical Elements in the Successful Application of Hybrid Tactics (Master’s thesis). Prague: Charles University, <accessed online: https://dspace.cuni.cz/bitstream/handle/20.500.11956/124589/120381167.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y>.

Stepyko, M. T. (2011): Ukrayinsʹka identychnistʹ: Fenomen i zasady formuvannya, [Ukrainian Identity: Phenomenon and Principles of Formation]. Kyiv: National Institute for Strategic Studies.